Lessons from a ‘devastating’ year with COVID-19

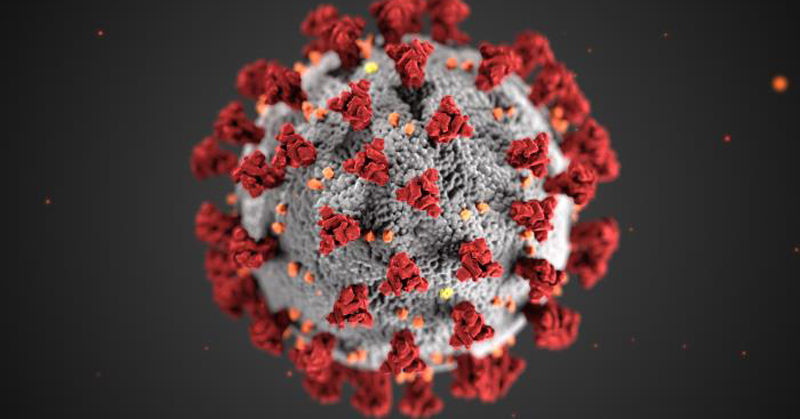

Photo courtesy of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention March 12, 2021

UD marks pandemic landmark with updates from researchers, medical officials

It was time for that annual checkup. But this year, the coronavirus (COVID-19) needed no formal introduction.

It had been a year since March 11, 2020, the day the World Health Organization declared the virus to be a global pandemic and the state of Delaware announced its first case.

Back then, the word “coronavirus” was still a novel concept to most. COVID-19 had not been seen before December 2019. And the University of Delaware hosted a 90-minute panel discussion at Mitchell Hall, sharing information from experts in medicine, public health and history to help people grasp what was happening.

After a yearlong crash course on the virus, a year that saw more than 529,000 deaths in the United States and more than 2.6 million globally, UD’s College of Arts and Sciences hosted another 90-minute panel. This time, the event was held virtually. It provided an update on research and the public health implications of the virus, its new variants and the vaccines that have emerged in record time.

More than 300 people participated in the webinar, which was recorded on Zoom by University Media Services and can be viewed at this website. They heard examples of the hard virus-related work many disparate professionals have been doing. They heard cautious optimism.

And they heard again of the strain and loss experienced by so many.

“This crisis has eclipsed any public health emergency response we’ve ever been involved in,” said Dr. Karyl Rattay, director of Delaware’s Division of Public Health, “as far as time, magnitude, complexity — and the loss of life is devastating.”

COVID-19 has claimed almost 1,500 lives in Delaware in the past year and almost 90,000 cases have been reported.

By contrast, in a regular flu season Delaware might lose 15 people, Rattay said, and its worst flu season ever took 38 lives.

This past whirlwind year brought extraordinary pressure to health systems, exposed many pre-existing inequities and required much collaborative effort, Rattay said.

The rapid spread of the virus demanded quick response and caused unprecedented upheaval. UD closed down almost everything on campus, for example, moving to a virtual environment and reopening gradually as conditions changed.

“I don’t think any of us had any idea what the year was going to bring to our campus, our state, our country and our world,” said UD Provost Robin Morgan. “We are so fortunate to work in a community where there are people who can better help us understand this coronavirus.”

Testing and contact tracing have been key to tracking the disease and efforts to slow the spread. Rattay thanked the University for its partnership in testing, which has helped give Delaware one of the highest testing rates in the nation.

Already, more than 270,000 vaccines have been administered in Delaware, Rattay said. As eligibility widens and dosages become more readily available, those numbers will increase.

“Equity is a real issue,” Rattay said. “We need to meet people in their communities, where their leadership, pastors and trusted champions are getting vaccinated and encouraging others to get vaccinated. We are focused on the many barriers among our higher-risk populations.”

As vaccination continues, people should still wear face coverings and maintain physical distance, she said.

During a question-answer period, Rattay said she is glad UD established a program in epidemiology. The program is one of the newest in the College of Health Sciences, founded in 2018 when Prof. Jennifer Horney joined UD’s faculty.

“If we could rewind to a decade ago, that’s where I wish the state had done some things differently,” Rattay said. “We were really weak in epidemiology.”

UD’s epidemiology students have been very helpful during the past year, she said.

She also wishes the state had updated its data structure for laboratory reporting.

“It was just about to be modernized, but the pandemic really hit us and the system wasn’t ready for the quantity of labs we needed to take on,” she said.

“I also wish we had known how common asymptomatic spread would be. We didn’t think masks were necessary at first, except for symptomatic people.”

She finds it interesting that many other respiratory infections have been almost non-existent this past year and believes many will feel more comfortable wearing masks and face coverings in the future.

“A lot of lessons have been learned along this journey. We don’t ever want to go through this again, but we probably will and we’re in a better place now to handle this than we were a year ago.”

Many UD researchers discussed the work they have been doing during the COVID outbreak. Among them:

Norman Wagner, Unidel Robert L. Pigford Chair in Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering, talked about the novel modeling and surveillance system — Project Darien — he and his collaborators developed to show students how their actions could affect case rates in the UD area and help inform health policymakers.

The results reinforce the guidance to wear face coverings and practice physical distancing is important. The effort will provide useful tools as other diseases emerge in the future.

“What we’re finding from surveillance — wear your mask and social distance,” Wagner said. “Those things really matter…. We need to get those compliance rates up pretty high.”

Calvin Keeler, interim dean of the College of Agriculture and Natural Resources, professor of molecular virology and an expert in respiratory viruses in birds, explained how variants arise in the COVID-19 virus with its spike-shaped proteins.

Mutations are common in viruses, he said, and thousands already have been identified as COVID-19 genomes have been sequenced. Scientists can track those mutations.

Not all of those changes strengthen the virus.

“Some can slow it down,” Keeler said. “That’s what happened to the SARS virus. Some mutations have no effect on the virus. Others may help it spread faster or evade the immunity response, giving it an advantage.”

While all three vaccines to date are effective at preventing serious illness, hospitalization and death, they do not eliminate viral replication and “shedding,” he said.

“That’s why you still wear a mask even when you’re vaccinated. You might feel fine, but still can pass it on to someone else.”

Esther Biswas-Fiss, professor and chair of medical and molecular science, said the variants could affect diagnostic testing if they affect the ability to detect the presence of the virus. Her department trains individuals for work in clinical and diagnostic laboratories and careful attention is given to that viral evolution.

“Because tests target such broad spaces in molecular diagnostic testing, it’s unlikely the tests we have will be affected,” she said. “But labs producing and conducting tests are continuously checking on that possibility.”

Biswas-Fiss said it is important to provide sensitive, accurate tests all over the world, including places that do not have sophisticated equipment.

Eric Wommack, deputy dean of the College of Agriculture and Natural Resources and professor of environmental biology, talked about a project he and Prof. Kali Kniel (microbial food safety) conducted, testing wastewater samples to understand the presence of COVID in New Castle County and on the UD campus. They established a center in the process — the Center for Environmental and Wasterwater-based Epidemiological Research (CEWER).

“The virus is shed in feces, even though it is a respiratory virus for the most part,” Wommack said. “Asymptomatic or pre-symptomatic individuals shed the virus in fairly high levels, so wastewater is a leading indicator of infection.”

The data they collected helped New Castle County know where the virus was moving within the county.

“It’s a critical point to make — if you slow the infection rate, you slow the replication rate and that slows down the emergence of new variants,” he said.

John Jungck, professor of biological sciences and mathematical sciences, talked about how evolution and mathematics are crucial to understanding molecular information, where the virus came from and how using that information is critical to understand how it is changing.

Jennifer Horney, director of UD’s epidemiology program, said the vaccination trends are moving in the right direction.

“Many are impatient for their turn to come, but the process is getting faster every day and we’re getting more doses out all the time,” she said. “But there is striking inequity among people getting vaccinated early on.”

People at higher risk must have high priority, she said, along with those in the essential workforce, many of whom are from minority populations.

“Vaccinations are also a critical piece of improving mental health, particularly for the elderly who have been so isolated over these past 12 months,” she said.

Carolyn Haines, director of UD’s Nurse Managed Primary Care Center, talked about being a frontline provider over the past year.

Following the guidelines — wearing face coverings and observing physical distance — has protected her team, which returned to campus in June.

“We have had nursing students with us and patients in-person and have had no exposures within our subset,” she said. “Following the guidelines works.”

Many patients also were seen by way of “telehealth” — using videoconferencing, emails and phone calls — and Haines hopes that is here to stay.

“The mental-health aspects of this have been huge,” she said. “People are feeling isolated, not able to leave their homes. We have seen many with mental-health issues who previously had none.

“I’m hoping this brings us out smarter and wiser to act on this better next time.”

For more information

The University has an extensive communications strategy, including an online COVID-19 dashboard that provides data on testing and cases, a “Protect the Flock” campaign to reinforce healthy protocols, webpages and videos offering regularly updated information for all in the UD community and an ongoing quick-response center that fields questions and concerns by email.

The state of Delaware maintains its own COVID-19 data dashboard, call centers and provides regular briefings on COVID response.

Contact Us

Have a UDaily story idea?

Contact us at ocm@udel.edu

Members of the press

Contact us at 302-831-NEWS or visit the Media Relations website