Delaware Bay skates

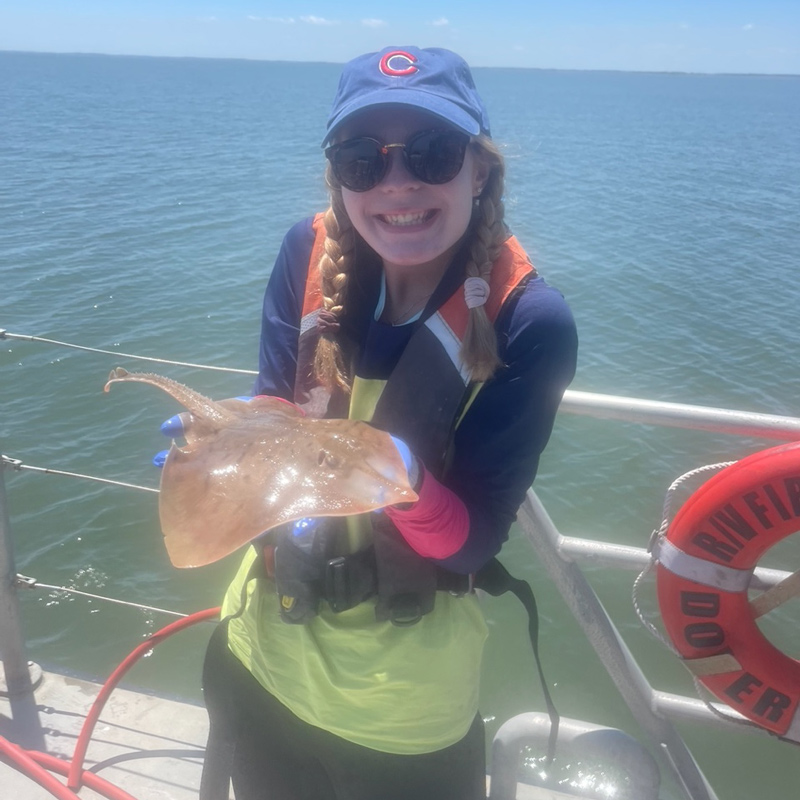

Photos courtesy of Caroline Bowers September 15, 2022

UD undergraduate spends summer researching clearnose skates

The clearnose skate is the most common skate in the state of Delaware. The clearnose skate is so common that it is despised by anglers who will often catch them by accident when fishing for other species.

Just because it is so common, however, doesn’t mean that it is well understood. Because of this, University of Delaware undergraduate student Caroline Bowers, who is in the Honors College, conducted research on the clearnose skate to get a better understanding of their diets for her project as a UD Summer Scholar.

Because clearnose skates migrate from the Gulf of Mexico, Bowers’ research focused on what the skates eat while in the Delaware Bay compared to what they eat during their time in the Gulf of Mexico.

To do this, Bowers went with members of the Delaware Division of Fish and Wildlife when they conducted their monthly bottom trawls.

“They get a lot of skates on those trawls,” Bowers said, a junior marine science major with a concentration in marine biology. “The first one I went on, we got about 40 different skates.”

Bowers took mucus and muscle samples from the skates, as well as blood samples from a subset. The reason for taking these diverse tissue samples is that the different tissue samples have different turnover rates — the time it takes for 50% of the stable isotopes in their tissues to be replaced by the stable isotopes in their diets.

“Blood and mucus are going to have much faster turnover rates of tissue than muscle tissue,” Bowers said.

For example, if the skates had been in the Delaware Bay since April and she took blood samples in June, the blood samples would reflect what they were eating in the Delaware Bay. However, if she did the same thing with muscle samples, which have a slower turnover, the muscle samples from June would reflect more of what the skates were eating during migration.

“When I look at the muscle samples from August, it’s going to reflect more of what’s in the bay,” Bowers said. “That’s how we tell the difference in their diets.”

After taking the samples in the field, Bowers analyzed them in the lab. She conducted her research in the lab of Aaron Carlisle, assistant professor in the School of Marine Science and Policy, which is part of the College of Earth, Oceans and Environment. She was looking for isotopes of carbon and nitrogen, two natural tracers that allowed her to determine what the skates had been eating.

“Basically, there’s two different versions of the same element: there’s light carbon and there’s heavy carbon — they just have a different number of neutrons in the nucleus, which means an extra neutron makes it heavier,” Bowers said. “Heavy carbon is heavy, like the name implies, and it accumulates. So if I’m a predator and I eat a fish that’s eaten something else, the heavy carbon has accumulated in that fish and will accumulate in the predator.”

By looking at the ratios of heavy carbon to light carbon and heavy nitrogen to light nitrogen, Bowers was able to compare the isotope ratios of the skates to the isotope ratios in the tissue samples from prey species in the bay.

“If a skate’s isotopic ratios look similar to this prey species’ isotopic ratios, we can assume that they are eating that prey item,” Bowers said.

It is important to know what the skates are feeding on for conservation purposes.

For example, because skates are mesopredators — a mid-ranking predator that feeds on smaller fish — in the Delaware Bay, they have top-down control over food webs and as a result, the ecosystem.

One of their potential prey species is the Delaware State fish, the weakfish, whose population numbers are down.

“Obviously, if they are eating a lot of weakfish, that could be a potential stressor on the weakfish populations so that’s a good thing to know,” Bowers said. “Or maybe there’s some other effect with the weakfish population being lower. Now the skates have to put more pressure on something else so that will influence ecosystem dynamics. It’s good to know what’s going on in the bay, especially when it comes to conservation.”

Bowers is planning to continue this research — both collecting and analyzing data — as her senior thesis. Carlisle said that Bowers was a great addition to his lab this summer and that he is excited to see how her projects turns out.

“Caroline was a hard worker, helped with many ongoing research projects going on in the lab, and importantly, she was very organized, motivated, and good in the field,” Carlisle said.

Having grown up in the Midwest, Bowers said that she got interested in the ocean from family trips to the East Coast every summer. She also grew up going to the Shedd Aquarium in Chicago, and once she took an oceanography course in high school, she knew that she wanted to pursue marine biology as an undergraduate.

“I never really considered marine biology as a valid career option because I was surrounded by corn, but when I took that oceanography course, I loved it,” Bowers said. “I chose UD because of their marine science program.”

She also noted that the Summer Scholars program was beneficial in many ways, from getting hands-on research experience to learning about other projects going on by other students in the program.

“Even though I had my own project I was working on, I was in a lab with tons of other graduate students who were super helpful. I couldn’t have done it without them. It was cool to learn about and help out with their projects,” Bowers said. “I did not do this research all by myself. Everyone from Dr. Carlisle, the Delaware Division of Fish and Wildlife, a couple of the graduate students — Devon Scott and Bethany Brodbeck, specifically — were humongous helps to me. Science is really a team effort and even if it’s my project, I’m not alone.”

Contact Us

Have a UDaily story idea?

Contact us at ocm@udel.edu

Members of the press

Contact us at 302-831-NEWS or visit the Media Relations website