Unraveling the mystery behind stuttering

Photos by Ashley Barnas July 27, 2022

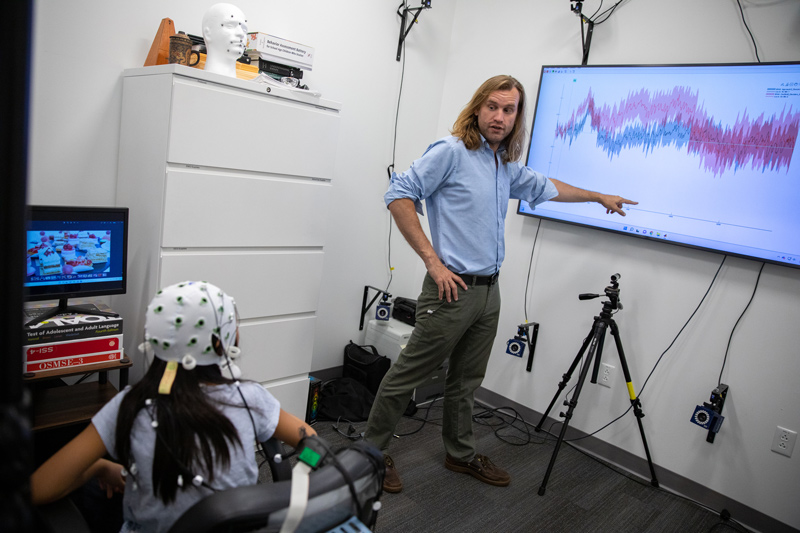

UD researchers study the brains of children with persistent stuttering to determine what hinders recovery

When Evan Usler was just 6 years old, he knew his stuttering would persist into adulthood. He was among the one in 10 children who develop a stutter at a young age. Most children who stutter recover regardless of therapy or intervention. Usler was among the 20% who did not recover.

“When I was a child, there was this notion of ‘let’s just wait and see.’ The pediatrician and speech-language pathologist were limited in the information they had, and they thought I would recover,” Usler said. “I knew then, I’m not recovering from this. This is a problem. It was one of the first times as a child when you realize older adults may not know what’s best for you.”

Now, Ho Ming Chow, an assistant professor in the Department of Communication Sciences and Disorders, has been awarded a $3 million grant from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services to investigate the differentiating characteristics in the brains of kids whose stuttering persists later in life. He's teamed up with Usler, also an assistant professor in the CSCD Department who will serve as a co-investigator, on this five-year research project.

“In one study, we found one part of the brain is atypical in people who stutter, but another study had completely different findings. So that’s why we suspect that even in the brains of people who stutter, there are multiple causes in the brain revealing why the presentation of the disorder varies in different people,” Chow said.

Using structural and functional MRI (FMRI) and electroencephalogram (EEG), the researchers in the College of Health Sciences aim to determine what prevents some children from recovering on their own. Their findings could impact therapies in children who stutter and improve outcomes.

Stuttering disfluencies take on three identifiable behaviors: repetitions at the beginning of words, prolongations of words, or a silent block, in which it’s evident a person is trying to say something, but the words just aren’t there.

“We may think it’s a normal part of speech-language development that children produce these stuttering disfluencies, but that doesn’t appear to be the case. In as much as 10% of these children, they’re developing these atypical stuttering-like disfluencies,” Usler said.

As more research examines brain activation during speech production and disfluent speech, Usler said there’s been mixed findings.

“There doesn’t seem to be a brain signature associated with a specific type of disfluency. If someone repeats words, we don’t see a distinguishing characteristic in the FMRI,” Usler said. “In the past, we’ve just looked at behavior and tried to categorize it that way, but that only gets us so far. By looking at the brain, we’re looking at more potential subtle subtypes that may not be evident on the behavior level.”

UD is teaming up with the University of Michigan to enhance data collection for the study which will begin after the school year starts in late September or early October.

“We have access to the largest neuroimaging data set in the world so we can do this type of research,” Chow said. “We have sufficient preliminary data to show there’s a possibility that there are different subgroups in children who stutter.”

For now, study participants will include children who stutter between the ages of 6 to 13 years old, but researchers may lower the age range to include children ages 3 to 5 years old to account for stuttering onset.

“If we want to understand why some children recover from stuttering and why some children have persistent stuttering, we must start with a younger age group so we can follow them for a number of years,” Chow said.

Studies have shown young boys, who are lagging most in speech language and motor development, have an increased risk of stuttering persisting into adulthood. Family history and genetics are also factors in stuttering persistence.

But brain structure and function are believed to be at the core of the speech disorder. In a past genetics study, Chow said brain imaging showed an abnormality in the subcortical areas and the corpus callosum, which connects the left and right sides of the brain, permitting communication.

“We don’t know exactly why that affects speech, but if the corpus callosum is related to stuttering, we can decide different therapies to enhance the connection between the left and right hemispheres of the brain,” Chow said.

Another portion of the brain that may be tied to stuttering includes the basal ganglia which plays a critical role in motor learning, behavior, and emotion.

Their findings will help speech-language pathologists best allocate limited resources and ultimately impact treatment for children who stutter.

“Once we confirm the neural subtypes associated with stuttering based on the atypicality in each subtype, we can determine the most effective therapies for children who stutter,” Chow said. “Depending on what kind of behavior characteristics and anatomical structures are associated with each subtype of stuttering, we can design different therapies.”

While this five-year research grant focuses on children whose stuttering persists, UD is in a unique position to study the complex human social behavior on various levels.

“Stuttering involves genetics, neurology, psychology, and individual labs may focus on one of those levels,” Usler said. “At UD, we can look across those different levels by examining gene mutations in animal models, neuroimaging of young children, and behavior and EEG activity to determine how cognition and motivation in real-time during various speaking tasks may affect whether one has a moment of stuttering or how severe the stutter may be.”

Determining specific neural subtypes associated with how stuttering manifests in each child, Usler said, will lead to better clinical decisions at UD’s Speech-Language-Hearing Clinic and beyond.

“What if we find neural risk factors of stuttering severity that in the future gives us some idea which children are not likely to recover on their own?” Usler said. “Perhaps that’s a subpopulation that should receive speech therapy resources as soon as possible.”

UD’s goal is to become a leading center for stuttering research with the assistance of the UD community and local Delawareans. If you’re a person who stutters and would like to assist researchers with this project or desire more information, please contact via email stutteringproject@udel.edu.

Contact Us

Have a UDaily story idea?

Contact us at ocm@udel.edu

Members of the press

Contact us at 302-831-NEWS or visit the Media Relations website