Arctic undergrad

Photos courtesy of Rachel Roday March 13, 2020

UD student joined trip with faculty to research polar night biological impact on species

University of Delaware Associate Professor Jonathan Cohen has been travelling to the Arctic to conduct research on the biology of species during the polar night since 2012. While he has had master’s level and doctoral level students accompany him before, he never had a UD undergraduate on board with him until this year.

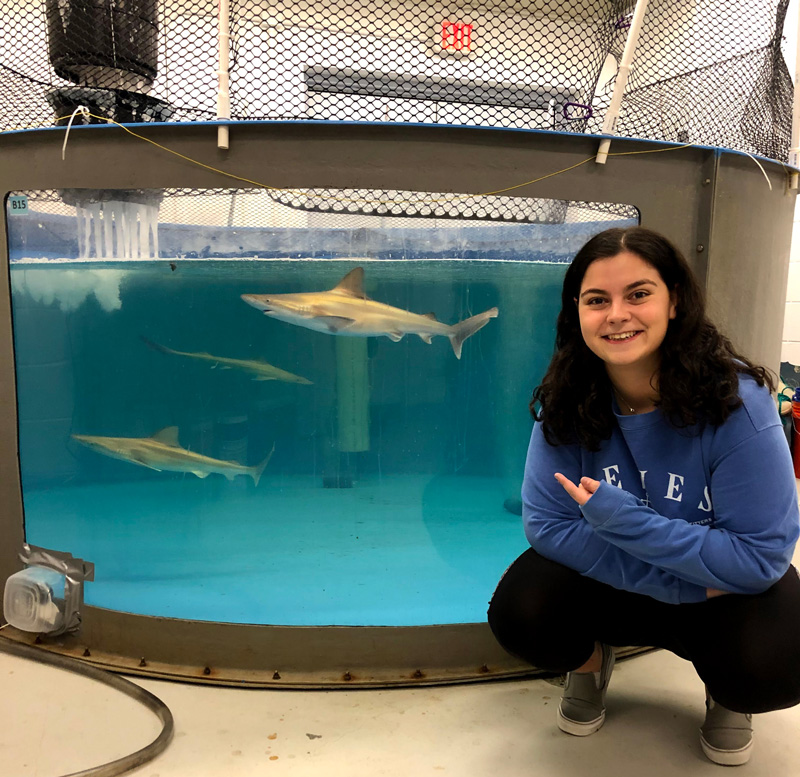

Rachel Roday, who was the only undergraduate student on the cruise, had previously worked with Cohen and Aaron Carlisle, an assistant professor with Cohen in the School of Marine Science and Policy (SMSP), which is part of the College of Earth, Ocean and Environment. Roday’s work as a Summer Scholar focused on researching oxygen consumption in sharks. Cohen asked Roday to accompany him on the cruise because they would be doing comparable measurements on the ship in terms of measuring oxygen and metabolism.

“Rachel did great over the course of the cruise,” said Cohen. “She anticipated the work that needed to be done and pitched in whenever she could. She carved out a little niche of things that she was working on that was very productive. I think she gained a lot and she contributed a lot to the whole project.”

Roday, a junior Honors student double majoring in marine science and biology, was able to go on the cruise thanks to funds from SMSP and an Honors Enrichment Award. She had never been to Europe before the cruise and had never experienced such low temperatures.

Working around the Svalbard area, a land mass north of Norway located between the Arctic Ocean and the North Atlantic, Roday said it was incredible to experience the polar night.

“Being up there in complete darkness was amazing. Even at 11 a.m., the only light was from the moon,” said Roday.

Roday assisted Cohen in his research looking at how organisms respond biologically to the low levels of light in polar night, trying to understand circadian rhythms in marine organisms.

“An example of a circadian rhythm is that you wake up at the same time every day because your body’s internal clock is anticipating the arrival of morning,” said Cohen. “Circadian rhythms anticipate changes in the environment over the 24-hour day.”

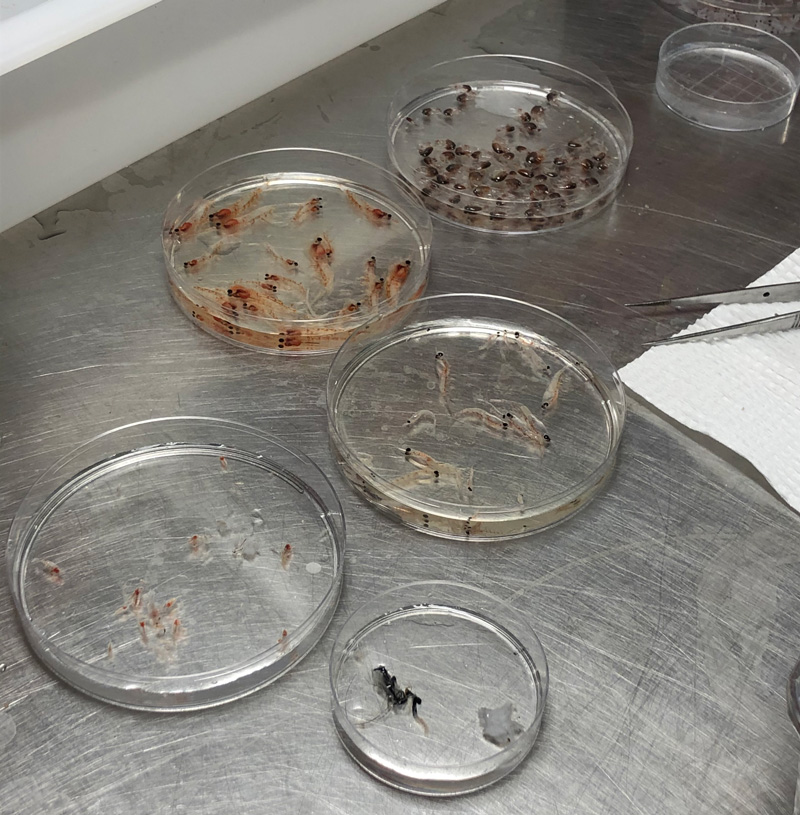

They collected minute crustaceans called copepods, specifically Calanus, an organism that plays a major role in the Arctic food web, eating phytoplankton and then getting eaten itself by fish, birds and whales.

The researchers conducted experiments looking at the copepods’ activity in small chambers with a set of behavioral activity monitors.

The goal was to see how the animals act at different latitudes during different times of the year to try to understand if they are able to detect the light that’s around them and use that light to set their biological clocks. They ultimately want to determine whether the biological clocks of the copepods still function at these high latitudes with little to no light levels.

“We’ve been measuring light in these places and there seems to be enough light even during the polar night for these animals to see,” said Cohen. “They may actually tell us that the animals are capable of detecting what doesn’t seem to be enough light for us, and with that light, they can set their clocks and avoid getting eaten.”

For the circadian rhythm experiments, Roday was involved with seeing how bursts of light affect the copepod’s behavior using a locomotor activity monitor (LAM), consisting of a beam of light and a test tube. When the copepod swims up and down in the test tube, it breaks the light beam, which enables the researchers to track its behavior under different conditions.

Cohen said that they have been conducting those experiments during different seasons, different times of the year, and different latitudes to try to get a global sense of how these organisms respond.

“As the Arctic warms and North Atlantic species become more a part of northern latitudes, we want to determine if there are other breaks on how a species range can expand apart from temperature,” said Cohen. “There are plenty of places around the world where you have cold temperatures, but it’s the timing of the light and the dark cycles that make the polar environments extreme.”

To look at the behavior of the copepods in the LAMs, the researchers changed the amount of light they were getting during daily cycles. For an entire week, some of the copepods would be in complete darkness to mimic the polar night, some would have the light on 24 hours a day, and some would have varying hours of light and dark.

“We were giving them different day lengths to see how their behavior would change to quantify their swimming responses,” said Roday.

Another experiment looked at the respiration of the copepods at different temperatures.

“We put them in a well-plate, which is a plate with 24 little tiny wells, a copepod in each one, and measured how much oxygen was extracted from the water over a given amount of time,” said Roday.

Temperature is critical for the copepods’ metabolic rate because they can’t control their internal temperature. When the ocean temperature increases due to climate change, their metabolic rate will increase as well, so the researchers looked at rhythmic activity in oxygen consumption — which is used as a proxy for metabolism — and looked for any evidence of circadian rhythms in how the organisms reacted to those temperature increases.

Roday said that getting to travel to the Arctic to conduct research was a great experience and that as an undergraduate, she feels it is important to get exposed to as many opportunities as possible in order to figure out what she wants to do.

“The more opportunities and experiences you’re exposed to, the more likely you’ll be happy and successful in the future,” said Roday. “I try to do as much as possible, have different jobs and research experiences in marine science so I can find the thing that I’m truly passionate about. This experience taught me that I really like field work and being on a boat, and so in the future, I’d like to do more of that.”

Contact Us

Have a UDaily story idea?

Contact us at ocm@udel.edu

Members of the press

Contact us at 302-831-NEWS or visit the Media Relations website