The Science of Saliva

Photo courtesy of Swati Pradhan-Bhatt, Christiana Care Health System May 03, 2018

NIH director Francis Collins highlights work by UD researchers

Editor’s Note: Francis Collins, director of the National Institutes of Health, wrote a blog post on Thursday, May 3, about research on saliva done by a team from the University of Delaware and the Christiana Care Health System. The blog post is reprinted here with permission of NIH. The image used in this story and Dr. Collins' blog post came from UD's Art in Science event, which showcases cutting-edge research through beautiful images. The 2018 show opens Friday May 4 at 5 p.m at Blue Ball Barn, Alapocas State Park.

Whether it’s salmon sizzling on the grill or pizza fresh from the oven, you probably have a favorite food that makes your mouth water. But what if your mouth couldn’t water—couldn’t make enough saliva? When salivary glands stop working and the mouth becomes dry, either from disease or as a side effect of medical treatment, the once-routine act of eating can become a major challenge.

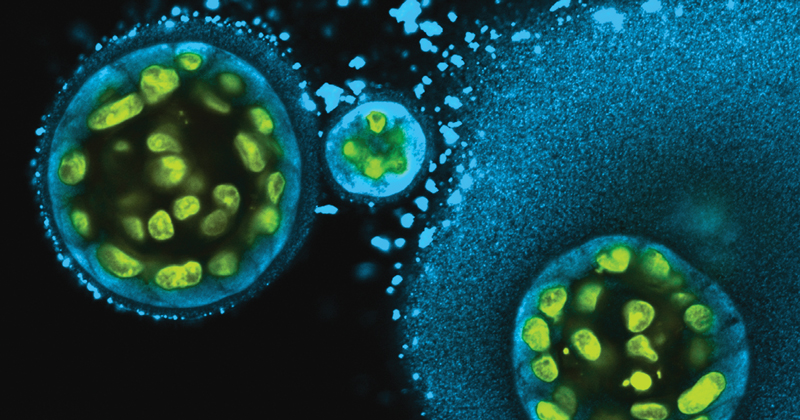

To help such people, researchers are now trying to engineer replacement salivary glands. While the research is still in the early stages, this image captures a crucial first step in the process: generating 3D structures of saliva-secreting cells (yellow). When grown on a scaffold of biocompatible polymers infused with factors to encourage development, these cells cluster into spherical structures similar to those seen in salivary glands. And they don’t just look like salivary cells, they act like them, producing the distinctive enzyme in saliva, alpha amylase (blue).

Although our mouth is lined with hundreds of salivary glands, more than 90 percent of saliva comes from just three pairs of these glands (parotid, submandibular, and sublingual). The three vary in size and shape, but share the same “cluster-of-grapes” design. The “grapes,” or acinar cells, secrete a saliva precursor into the “stalks,” or ductal cells, which modify the chemical composition of the saliva and convey it into the mouth.

In 2005, then-graduate student Swati Pradhan-Bhatt joined a team of researchers including Cindy Farach-Carson, Robert Witt and Xinqiao Jia from the University of Delaware, Newark, and the Christiana Care Health System, Newark, DE, in a bold attempt to engineer an implantable replacement salivary gland. Pradhan-Bhatt was asked to figure out a way to culture acinar cells. She was forewarned that, based on several failed attempts by other groups, acinar-like cells are notoriously difficult to isolate from salivary tissue and to grow well outside of the body.

Pradhan-Bhatt soon made a crucial discovery: salivary gland tissue contained previously unknown human stem/progenitor cells (hS/PCs) [1]. Under the right conditions and with the right biological prompts, these salivary hS/PCs can produce all of the cell types needed to make a salivary gland, including the secretory acinar-like cells. With some NIH support, Pradhan-Bhatt and her colleagues developed a 3D system to grow acinar cells from a parotid gland, encourage them to cluster, and even get some to secrete saliva [2].

Many technical challenges remain to engineer a full replacement salivary gland. But with a source of acinar cells, Pradhan-Bhatt and colleagues may have already crossed an important threshold. For patients with head and neck cancers, radiation is a common treatment to shrink the tumor. Unfortunately, radiation often severely damages the salivary glands’ acinar cells, even though their ductal cells remain operable. So, it may be possible one day to graft replacement acinar cells onto the ductal cells to boost saliva production.

Pradhan-Bhatt continues to work on this project, which has resulted in some groundbreaking publications and many fascinating images. That includes this image, which was among those featured in the University of Delaware’s 2017 Art in Science exhibit.

Reference:

[1] Primary Salivary Human Stem/Progenitor Cells Undergo Microenvironment-Driven Acinar-Like Differentiation in Hyaluronate Hydrogel Culture. Srinivasan PP, Patel VN, Liu S, Harrington DA, Hoffman MP, Jia X, Witt RL, Farach-Carson MC, Pradhan-Bhatt S. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2017 Jan;6(1):110-120.

[2] Implantable three-dimensional salivary spheroid assemblies demonstrate fluid and protein secretory responses to neurotransmitters. Pradhan-Bhatt S, Harrington DA, Duncan RL, Jia X, Witt RL, Farach-Carson MC. Tissue Eng Part A. 2013 Jul;19(13-14):1610-1620.

Links:

Dry Mouth (National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research/NIH)

Swati Pradhan-Bhatt (Christiana Care Health System, Newark, DE)

University of Delaware 2017 Art in Science

NIH Support: National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research; National Cancer Institute; National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences

Contact Us

Have a UDaily story idea?

Contact us at ocm@udel.edu

Members of the press

Contact us at 302-831-NEWS or visit the Media Relations website