An Ida B. Wells moment

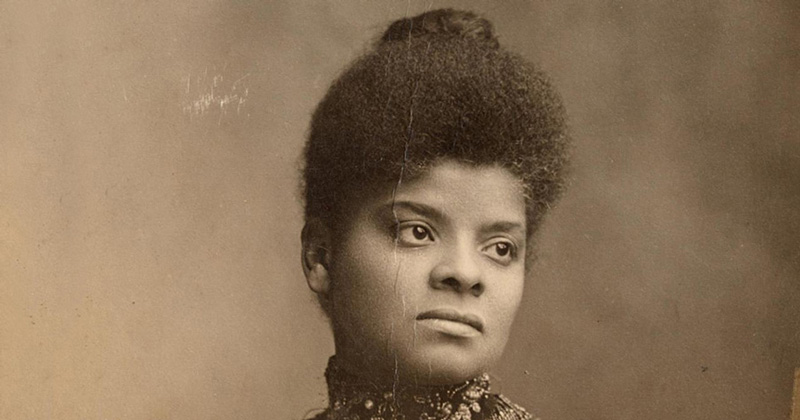

Photo courtesy of Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago Library September 25, 2018

Legacy of social-justice crusader draws renewed interest

The journalist and activist Ida B. Wells was so prominent in the late 1800s and early 1900s that The New York Times recently wrote that historians consider her “the most famous black woman in the United States during her lifetime.”

She became progressively less of a household name in the decades after her death in 1931, but Wells has recently been back in the public eye as the subject of news articles and editorials, podcasts, exhibits and memorials. In Chicago, a street has been named for her.

To refresh our memories of what we may — or may not — have learned about Wells (who was also known as Wells-Barnett) in history classes, Margaret Stetz shared some reflections on Wells life and legacy.

Stetz, who is Mae and Robert Carter Professor of Women’s Studies and professor of humanities at the University of Delaware, has taught many classes over the years that include Wells’ contributions to the civil rights and feminist movements. Stetz is also the author of an article, published in the spring 2018 issue of Americana: The Journal of American Popular Culture, examining how Wells has been represented in popular literature, including children’s literature.

Q: Why do you think that Wells seems to be attracting so much attention recently?

Stetz: This is certainly an Ida B. Wells moment. A number of things have contributed to this, including The New York Times series of “Overlooked” obituaries, in which they publish obituaries of important women — many of them women of color — who weren’t memorialized in the paper at the time of their deaths. They’ve published one on Wells, and they’ve also written an editorial praising Chicago for naming a downtown street for her. Then there’s the new National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Alabama, which has a section commemorating Wells and her tireless work as a crusader against lynching. And as recently as the end of August, the Washington Post put a podcast about Wells online as part of its “Retropod” series on historical figures.

Q: I understand after years of raising money and gathering support, her descendants are now ready to install a memorial in Chicago next year. Why is all this happening now?

Stetz: Ida B. Wells is a figure who represents resistance, and that’s a powerful message right now. She was such a fighter in so many different realms, for racial justice — especially as one of the founders of the NAACP — and for women’s suffrage, and was really an extraordinary writer, speaker and organizer. So this is the right political moment for people to pay attention to what she did.

Q: What should we remember most about her?

Stetz: She was extremely influential in her lifetime, and she lectured not just in the United States, but also in Britain in the 1890s. She was very savvy about leveraging economic pressure and moral pressure as she crusaded against lynching in the South. In her lectures and her writing, she refuted the idea that African American men were lynched because they had raped or assaulted white women, and she had the facts to back that up. At one time, because she was so popular as a public speaker, she was approached by an agent who guaranteed her a good income if she’d go on a lecture circuit but agree not to talk about lynching. Even though she needed the money, she refused. She also fought with white women who tried to keep her and other African American women from participating in the movement to gain the right to vote. But nobody ever could stop her.

Q: What do we know about her personal life?

Stetz: Ida B. Wells made choices in her personal life that were way ahead of the times. After she married and had a child, she continued to work and to do her anti-lynching lecture tours, with her baby in tow and with her husband’s support. She quite literally took her baby on the road with her, which was practically unheard-of in the early 1900s. And because of the subjects she was talking about, she was accused of every kind of low-life behavior you can imagine, being called a “harlot” and worse. If you see photos of her, you’ll notice that she dressed in extremely fashionable, respectable, businesslike clothing as a way of showing how absurd those accusations were.

Q: She suffered other hardships because of her work and her activism, didn’t she?

Stetz: Absolutely. When she did her first investigative reporting about lynching and published those articles and editorials in the newspaper she co-owned and edited [The Free Speech and Headlight], the paper’s offices were ransacked and the presses were destroyed by white mobs that vowed to kill her if she returned to Memphis. That’s when Wells moved, first to New York and then to Chicago, but she didn’t stop her activism. And she was threatened throughout her life because of her work.

Q: How do you include her in your own work?

Stetz: I started teaching about Wells in the 1990s in feminist courses at Georgetown University. Recently, I’ve been teaching works by and about her regularly in my Women and Gender Studies course at UD, "The New Woman in Black and White." For the journal Americana, I wrote about a variety of films, adult comics and plays, as well as children’s books, about her. I think the stories for children will guarantee her future fame. New generations should grow up knowing why they need to honor her.

Contact Us

Have a UDaily story idea?

Contact us at ocm@udel.edu

Members of the press

Contact us at 302-831-NEWS or visit the Media Relations website