Graduate Student uses Honey to Outsmart Mosquitoes: youtube.com/watch?v=Ot6ph5EP8Wk

Sticky situation

Photos by Kathy F. Atkinson | Photo illustration by Jeffrey C. Chase | Video by Max Dugan December 01, 2025

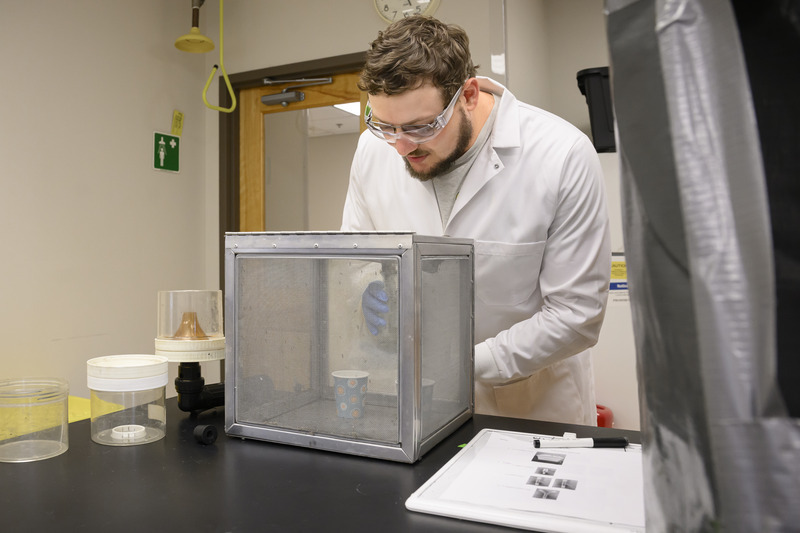

Graduate student uses honey to trick mosquitoes to give up saliva for virus testing

Delaware is among several U.S. states using chickens to detect pathogens that can be transmitted from mosquitoes to people.

These sentinel chickens are stationed in pens around the state in areas where mosquitoes are widespread. Mosquitoes bite the chickens, which develop antibodies to the pathogens West Nile Virus (WNV) and Eastern Equine Encephalitis virus (EEEV). That tells scientists these disease-causing agents are present.

The downsides? The chickens are expensive, labor-intensive and take time to yield results.

But a University of Delaware graduate student is testing a different method to monitor for mosquito-borne diseases. He’s trapping mosquitoes in the wild, enticing them with honey, and tricking them to give up their saliva, which he’s testing for viruses. The method isn’t new — it was developed in Australia. If it works in Delaware, it could be a cheaper, more accessible method to ultimately replace sentinel chickens, and could make Delaware a bellwether in U.S. mosquito testing.

Mosquito control innovation

Wil Winter was researching mosquito control and disease detection methods in 2021, when the environmental scientist for the Delaware Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Control’s Mosquito Control Section came across a method with a sweet touch.

He found that scientists in Australia were using small filter paper cards called FTA cards baited with honey. Mosquitoes fed on the honey, and in turn left behind their saliva on the cards. Scientists then extracted RNA from the saliva to test it for viruses.

Winter wondered if this method could be successful in the U.S.

“If it is, it could help other mosquito programs that can’t afford or don’t have the manpower to do any kind of arbovirus surveillance,” Winter said.

He contacted Vincenzo Ellis, an assistant professor in the UD Department of Entomology and Wildlife Ecology. Soon after, he enrolled in UD as a part-time master’s student studying entomology under Ellis’ guidance.

“I thought it was pretty interesting and was excited to participate,” Ellis said.

Delaware’s Mosquito Control Section’s mission is simple: reduce mosquito nuisance and protect public health by minimizing the risk of mosquito-borne illness.

It’s essential as Delaware’s warm, humid summers provide a perfect feeding ground for mosquitoes, like the species Culex pipiens Winter is studying.

Still, mosquito-borne illnesses aren’t common. In 2023, Delaware saw just four reported severe cases of WNV, all in New Castle County, and no cases of EEEV, according to data from the Delaware Department of Public Health. It’s likely cases are underreported since most people are asymptomatic or have mild symptoms.

Regardless of the data, health professionals and scientists are concerned because WNV and EEEV can cause serious complications and illness, like lifelong neurological impairment, especially in the young, the elderly, or those with weakened immune systems. And there are no vaccines for people.

“Mosquitoes are still the deadliest animal in the world,” Winter said. “Every year, 1-2 million people worldwide die from mosquito-borne disease, and it is estimated anywhere from 400-700 million people will contract a mosquito-borne disease. If our surveillance shows an area in the state with a lot of vector mosquitoes, we can conduct targeted control efforts to reduce mosquito populations in that area.”

A sweet trap

Mosquitoes love sugar. Throughout his research, Winter has tested different types of honey to determine which draws more mosquitoes to the filter paper. After trying locally produced honey from UD’s College of Agriculture and Natural Resources Apiary with little success, as well as Manuka honey, he’s still searching for the type of honey that will attract the most mosquitoes.

“Honey sits well on the card,” Winter said. “And due to its viscous nature, it doesn’t evaporate away, so the card kind of stays saturated.”

In the lab, Winter painstakingly identifies the mosquitoes he catches, looking specifically for mosquitoes in the genus Culex. He uses a microscope looking for hints of blue coloring in their stomachs. The coloration is from dying the honey blue, and signifies if a mosquito has fed on an FTA card.

“This takes a long time because you have to look at every mosquito and turn them over,” Winter said, “because sometimes it’s just the faintest coloration, where they just tested the honey out, but didn't fully feed.”

To confirm whether the collected mosquitoes have WNV or EEEV, Winter works with Brian Ladman, director of the UD Poultry Health System at the Charles C. Allen Jr. Biotechnology Laboratory, to extract RNA and test for viruses. Over the last couple summers, Winter has caught at least 30,000 mosquitoes and examined at least 10,000 for blue dye. Around 5,000 were Culex, which he tested for WNV and EEEV. The numbers do not include the mosquitoes he caught and analyzed from this past summer.

In total, 14 mosquito pools and five FTA cards were detected to have viruses.

“I’m confident if I can get Culex to feed at a rate of 80% or more consistently, this method will work as well as it does in other parts of the world,” Winter said.

Filling testing gaps and protecting public health

WNV and EEEV are two types of arboviruses — viruses transmitted by mosquitoes, ticks, and other insects. WNV was first recognized in North America 26 years ago, while EEEV’s presence in the U.S. dates back to 1938 in people, and possibly decades before, in horses.

Both viruses have been around for years, but state and local agencies still see gaps in monitoring them. It’s expensive to deploy sentinel chickens, and they require frequent antibody testing.

Delaware’s Mosquito Control Section has used sentinel chickens to detect EEEV since the early 1980s and WNV since the early 2000s. The FTA cards baited with honey and then coated with mosquito RNA reveal, just like the chickens, that viruses are circulating in a localized area.

“The chickens have their set locations,” Winter said. “Mosquito traps are much more mobile; you can set them essentially anywhere, and they’re a much cheaper alternative.”

Winter hopes the honey-coated FTA cards can make a difference for Delaware and other states, saving them money and time. Delaware’s sentinel chicken program costs about $50,000 each year to run. The FTA cards give scientists a more direct path to results, where they would just have to test the cards, not the mosquitoes themselves, for viruses. This new method could save the state about $35,000 a year.

Ellis said the research goes beyond helping states improve their mosquito testing methods.

“When people want to enjoy the outdoors, they must be aware of the infectious diseases they can pick up,” Ellis said. “It’s important to know about the risks of mosquito-borne illnesses and protect yourself.”

Winter’s dataset on where these arboviruses are sheds light on where people could more likely pick up a mosquito-borne disease. That makes the data crucial for protecting public health.

“People in public health, people in Mosquito Control where Wil works, will be able to make more informed decisions to protect us,” Ellis said.

Contact Us

Have a UDaily story idea?

Contact us at ocm@udel.edu

Members of the press

Contact us at mediarelations@udel.edu or visit the Media Relations website