'Game-changer’ Richard Leakey traces evidence of humanity’s origins in Africa

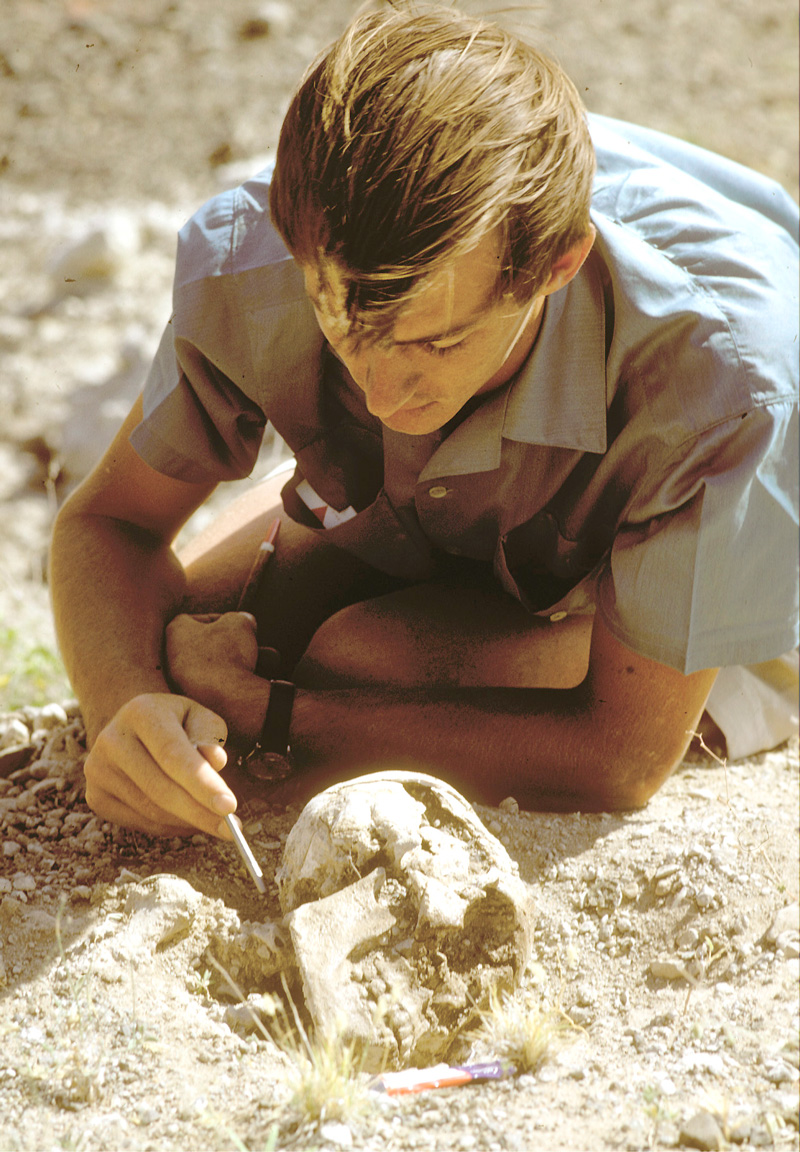

Photos by Kathy F. Atkinson and Evan Krape | Archival photos courtesy of the Turkana Basin Institute April 25, 2018

World-renowned paleoanthropologist says new technology, DNA analysis offer new insight on evolution

Those DNA ancestry tests so many people are having done might not tell you what Richard Leakey says is really true: Our deepest roots reach to Africa. Everything else is just a franchise.

Leakey, born in Kenya to British parents, told a University of Delaware audience there is no longer any doubt where human evolution began. Those who argued there was insufficient evidence when he and his family made their early fossil discoveries decades ago were right, he said.

No more.

“Fifty years ago, we really could have put most of our evidence on a small card table,” he said to a packed house in the Thompson Theatre at the Roselle Center for the Arts on Monday, April 23. Leakey’s lecture is available on UD’s YouTube channel. “Now this stage couldn’t hold it all. There are thousands of fossils.”

Leakey spoke at UD at the invitation of President Dennis Assanis, whom he first met at Stony Brook University. Assanis was provost at Stony Brook before taking the reins at UD in 2016. Stony Brook is the academic base for Leakey’s Turkana Basin Institute in Kenya and includes Leakey, his wife, Meave, and daughter, Louise, among its faculty.

“Richard Leakey is legendary for so many reasons,” Assanis said. “He and his family have been called the ‘first family of paleoanthropology.’ He is a conservationist, a politician, an activist and a wonderful human being.”

He also makes a mean London broil, Assanis said, and produces quality wine at his Kenya vineyard.

Leakey told a UD class earlier in the day that he is working to establish an “iconic” new structure in Kenya to celebrate Africa’s rightful status in world history. It would send a strong message to those still spreading racist, fascist views:

“It’s your motherland, so shape up,” Leakey said.

To those still disturbed by the word “evolution,” he offered another message during his afternoon talk.

“If the ‘e’ word still bothers you, let me say that there is plenty of evidence that humans have changed through time,” he said with a smile.

New technology and genetic analysis have added significantly to the scientific evidence, he said.

Leakey’s own evolution unfolded in the care of Louis and Mary Leakey, among the most famous archaeologists and anthropologists of the 20th century, credited with some of the world’s most significant fossil finds in Tanzania.

The Leakeys raised their three sons in Kenya, where Richard later made his own mark with a team that discovered extensive deposits of fossils and early tools dating to almost 2 million years ago.

His work in Kenya evolved, too, from fossil discovery to political office and leadership in conservation, where he could shape policy, fight corruption and stand against the devastating impact poachers and black-market ivory peddlers had on the elephant population.

He has continued his work and strong advocacy despite life-threatening situations, including a 1993 plane crash that forced amputation of both his legs below the knees. He had recent surgery to address skin cancer that had developed inside the lid of his left eye – and that eye was sewn shut.

He used a cane to steady himself and joked about that when he met with students in Munroe Hall.

“Without legs and only one eye—I have to be a bit cautious,” he said.

Now maybe. But his path in science, politics and conservation was marked with extreme opposition and peril - death threats, canisters of tear gas, dismissive critics, deadly plots.

Some dismissed him because he lacked the academic credentials others had earned.

“I was a high-school dropout,” he told the students. “I never tried to be anything.”

Instead, he was driven by curiosity. He listened a lot, he learned a lot, he absorbed a lot, he said.

With the great fossil hunter Kamoya Kimeu on his team in 1984, Leakey discovered “Turkana Boy,” the nearly complete skeleton of a pre-adolescent Homo erectus male, estimated to have died 1.6 million years ago.

“I accepted that I need other people to teach me things,” he said. “… And I was quite unfettered.”

Not that formal education is a waste of time. He spoke to that during a special 90-minute session at Munroe Hall, where students of Prof. Karen Rosenberg, a fellow paleoanthropologist, and Prof. Wunyabari Maloba, chair of Africana studies, gathered to talk with him.

“I don’t recommend you abandon your studies,” he said. “It’s a rough, tough world. But don’t worry about criticism either. Don’t be thin-skinned.”

Jorge Serrano, assistant professor of Africana studies, asked Leakey how he thought humanity might evolve in the next 15 generations.

“I don’t believe physical changes—in terms of what we look like—can happen,” Leakey said. “To make genetic selection stick, we have to isolate that population and need 200,000 years minimum.

“But evolution is happening. Other organisms are addressing genetic problems – microorganisms, viruses, bacteria. They could wipe out crops, animals, people. They’re moving at such a pace, we could easily see the appearance of new strains of a virus that could do things to us that we could not address enough to stop. We could have millions of people disappearing. The odds of that are very high. I’m not talking about extinction, but a huge reduction in numbers in the next 100 years. If it doesn’t happen in the next 100 years, that means we probably have figured it out.”

Kobe Baker, studying anthropology and Africana studies at UD, asked if conservation efforts are a losing battle.

“If you’re losing the battle, you don’t fight,” Leakey said. “It’s a battle we could lose, but we have to fight harder. We don’t have to lose everything.”

Maloba asked Leakey to explain to students why his work is important for humanity.

“With an intelligent brain—even a moderately intelligent one like mine—you have questions you want to ask,” Leakey said. “…With new techniques available, we can now learn so much. There is so much opportunity for anthropologists.

“And our shared origin is as inevitable, I’m afraid, as our shared destiny,” he said. “You can make a difference.”

Climate change plays a role in the environmental stresses all species face, he said. With oceans growing more acidic, melting ice at both poles and other rapid changes, “there may be serious collapses within several food chains,” he said.

Such phenomena have occurred before, he said, with extinction always the result.

“But humans weren’t there then,” he said.

During a post-lecture chat with Assanis, Leakey answered a series of questions and offered a few bits of advice to students considering their futures.

“Do things you enjoy doing—get joy out of what you do,” he said. “And try to be completely honest. Be direct, not rude. Be clear, not devious.”

Baker said he was thrilled to meet and hear from Leakey.

“You don’t get a chance to talk to someone who has made such game-changing discoveries very often,” Baker said. “You don’t get to meet someone like that every day. It’s almost surreal.”

Drew Brown, assistant professor of Africana studies, said Leakey plays a role in helping to complete the narrative around human origins.

“Even when it comes to the creation of races, anthropological findings are a major piece of that,” Brown said. “This creates Africa as being the cradle of such a great species. There is no way you can look at Africa or Africans as secondary to you or anything.

“With his work, he establishes the grounding in fact, rather than an agenda and ideology. There are certain things we can argue over, but with material facts it is easier for us to establish some of what Africa was, is and what it has created.”

Rosenberg was delighted to hear from someone who has transformed her field of study.

“He’s fabulous,” she said. “And for me what’s important—he’s talking about things we don’t have to speculate about. It’s evidence. When I was a student, we had to know every specimen. We were quizzed on it. Now, the fossil record has exploded so much, no one knows all of it—in a sense now we’re talking about little details—but the big picture is supported by overwhelming evidence.”

Leakey said he has found no evidence to support religious claims of human origin—a statement that drew applause from some in the Thompson Theatre—and he loses interest when such questions arise.

“Everything we find bangs another nail in the coffin of those myths,” he said. “I don’t see anything that supports a superior power.”

But scientific evidence of humanity’s emergence in Africa is established, he said, and the evidence allows for increasingly specific timelines.

“We all descended from a population that left Africa less than 100,000 years ago,” he said.

Furthermore, he said, pale skin—the kind Caucasians have—is a trait less than 10,000 years old. Blue eyes are less than 8,000 years old.

He doesn’t think there is such a thing as a black person or a white person.

“Black isn’t African,” he said. “White isn’t European. Go ask the Australian aborigine if he is African—but duck when you ask, because he’ll hit you.”

So if your family tree and that sketchy DNA sample say you’re from this place or that—go ahead. Wear your kilt, learn Spanish, make the family’s best-loved Thai recipe.

But remember your roots, Leakey would say. We’re all really from Africa.

Just a few more questions...and answers

Q: What are your views on ecotourism?

A: It’s an oxymoron. The best chance for wildlife is to leave it alone—not tromping around with Jeeps. But if there is no money, they can’t protect it. It’s really a very, very complex formula. A solution can be found, but I’m glad I’m not in charge now.

Q: What about all of the competition in science?

A: There is so much competitiveness in science now—and a lot of it is because of how you get grants. If Charles Darwin had to write an NSF [National Science Foundation] proposal today, we’d have never heard of him.

Q: What is left to be found?

A: Most of these fossils have been published as photographs—two-dimensional, blurry photographs. Today, to get anything published you have to have CT scans. What my daughter, Louise, is doing at africanfossils.org makes it possible to print out your own hominid fossils. You can cut them out from cardboard.

When my wife, Meave, finds something in Turkana and wants an opinion, she sends a scan to someone and gets information back. The other day she found a mandible—badly crushed. In the old days, we would have said it was not even worth collecting. But she sent it for micro CT scanning and a grad student at Stony Brook spent 70 hours—70 hours—on one tooth. And I can tell you these are teeth unlike any hominid teeth I’ve ever seen. The use of new technology is huge. I think it’s a base from which another 50 years of extraordinary work can be done. The golden years are ahead of us, not behind us. Just be tolerant of the shoddy work we did.

Q: You are a white Kenyan. A lot of people don’t know that is a thing.

A: I only run into that outside of Africa. How stupid were they to think Obama was not American? He identified entirely with America. If you identify completely, you can be completely identified.

Contact Us

Have a UDaily story idea?

Contact us at ocm@udel.edu

Members of the press

Contact us at 302-831-NEWS or visit the Media Relations website