Community conservation

Photos courtesy of Brian Griffiths and by Dylan Francis, Elizabeth Benson and Wilfredo Martinez | Photo illustration by Katie Young January 28, 2026

UD alumnus Brian Griffiths supports Indigenous Peruvian Amazon community goals

As a University of Delaware undergraduate student, Brian Griffiths, a UD Class of 2016 plant science and environmental engineering double major, felt a spark for a latent passion in the Amazon.

He participated in a research expedition focused on connecting humans with the natural world, where he learned from Indigenous communities who hunt and fish for their food while managing their natural resources to sustain animal populations rather than drain resources.

“For the first time,” Griffiths said, “I got to see what conservation was.”

The trip was so eye-opening that Griffiths kept going back. It inspired his human ecology career — incorporating a love for the natural world, problem-solving skills and a burgeoning interest in wildlife conservation.

Experiential learning

Griffiths was looking for summer fieldwork when he came across the conservation nonprofit Amazon Center for Environmental Education and Research (ACEER) Foundation.

Experiential education in the Amazon piqued his interest. Growing up on a farm, he always enjoyed being outside.

Ultimately, he didn’t get the internship. The foundation, instead, encouraged him to apply for UD’s Amazon research expedition.

Griffiths applied, marketing his proficiency in Spanish, knowledge of plants and farm background. To his delight, he got accepted. The expedition, led by Jon Cox, associate professor in the Department of Art and Design, gave a three-week crash course conducting fieldwork in collaboration with an Indigenous community.

“I got excited about science again,” Griffiths said.

Griffiths closely watched and listened to his surroundings in the rainforest, learning to value science through observation.

Aiding natural resource management

Since the expedition, Griffiths’ passion for the Amazon has grown.

He isn’t a typical conservationist. While many focus on preservation and rehabilitation of wildlife, Griffiths utilizes conservation of biodiversity to create sustainable sources of income.

In 2018, Griffiths moved to Sucusari, Loreto, Peru, as part of his Ph.D. and Fulbright fellowship. He lived among the Maijuna community, a rural Indigenous community of approximately 170 people.

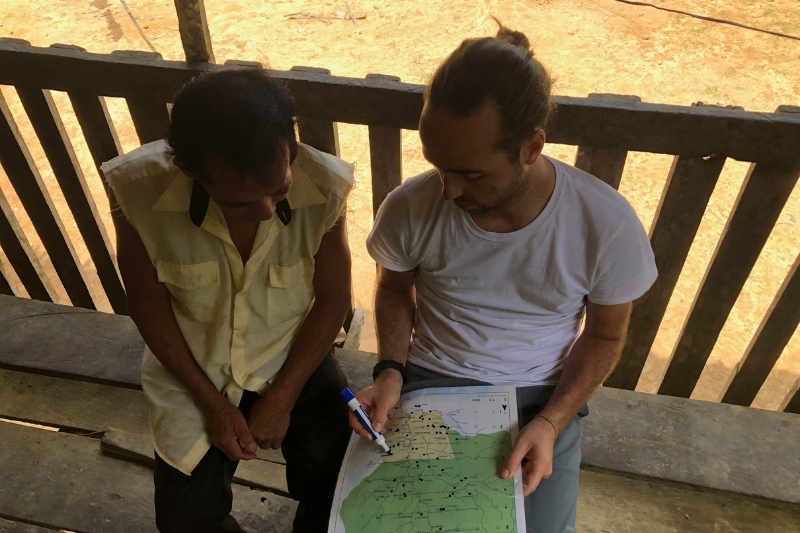

The Maijuna needed a scientist to work on a management plan detailing their hunting and conservation goals. Griffiths filled that role.

“In a community-based conservation system, if everything is built correctly, then not only is there no overhunting, there is also no incentive to overhunt,” Griffiths said.

Griffiths engaged with the Maijuna each day for over a year. He ate with hunters. He lived with different families. They even built him a small house made from forest materials.

Griffiths aspired to learn how overhunted mammal populations recover, how much hunting the Maijuna were doing and the pressure it put on animal populations. He deployed camera traps to detect movement and monitor the area’s mammals. He interviewed hunters about where and when they hunted, what animals they killed and what they did with the meat.

The research dataset showed hunters’ behavior, where the meat goes and hunting’s financial implications. Griffiths has now collected data for several years showing the scale of mammal populations.

“If mammal populations start to go down, then quotas under the management plan can be raised as well,” Griffiths said. “The plans’ restrictions adapt to the data.”

After his Ph.D., Griffiths reconnected with ACEER. At the time, Cox, who led UD’s Amazon expedition, was the foundation’s president.

Cox wanted Griffiths’ help reshaping ACEER to prioritize community-based work, so he hired him as executive director while Griffiths pursued a postdoctoral position at George Mason University. Once Griffiths finished his postdoctoral research, he became both an assistant teaching professor at Georgetown University and the president at ACEER, leading programs to develop environmental conservation leaders.

“It’s been almost 12 years since Brian went on his first trip with me to the Peruvian Amazon, and from that experience, it was clear how deeply he connected to the Amazon and the people who call it home,” Cox said. “Today, he is making a meaningful impact through interdisciplinary research with Indigenous communities, faculty and students from multiple institutions.”

Griffiths today is honed in on a battle brewing against a proposed highway for the Peruvian Amazon that would connect Iquitos in northeastern Peru to San Antonio del Estrecho along the Colombian border. The highway would go straight through the center of Maijuna ancestral lands.

“If this highway is built, it will result in irreparable harm to the Maijuna, their way of life, their food security and their economic stability,” Griffiths said.

Helping humans, wildlife and the environment coexist

Griffiths returns to the Peruvian Amazon for at least one month each year. It's important, he said, to understand human interactions with their ecosystems to find a happy medium where humans, wildlife and the environment can coexist.

“In many places, humans’ interactions with their ecosystems can result in unsustainability, and that can result in damage to their human system,” Griffiths said. “It’s about balance, mutual respect.”

The management plan Griffiths has worked on highlights helping the Maijuna find that happy medium and earn money through selling meat from animals they hunted. Griffiths’ work has even opened his own mind, shifting his perspective on hunting to see it as a way to sustain an ecosystem.

“These are people feeding themselves and their families, not people harming animals,” he said.

Griffiths is especially proud of a study he conducted on Amazon mineral licks, collaborating on papers with his mother, Lesa Griffiths Massarotti, professor in the UD Department of Animal and Food Sciences.

Mineral licks, natural sites where animals like porcupines and tapirs lick salts and minerals from soils and rocks for nutrients, are key hunting sites, a linchpin for the broader ecosystem.

“Mineral licks are notoriously difficult to study in the Amazon,” Griffiths said. “They’re really difficult to find unless people tell you where they are. They’re sort of holes of mud in the middle of nowhere.”

It turned out the main species hunters were after frequently visited mineral licks. Griffiths and the hunters identified more than 90 mineral licks in one watershed, elucidating their role in conservation and biodiversity.

Tangible skills

Griffiths has advice for future graduates: keep an open mind and build a community.

To facilitate experiential learning, an ACEER goal, Griffiths takes students into the Peruvian Amazon. They help him set camera traps and collaborate on research.

“When I’m seeking students to take into the field, they have to have very tangible skills. They don’t need to be ecologists. I can teach that,” Griffiths said. “I can’t teach being motivated and positive. I can’t teach the open-mindedness required for working with rural and Indigenous communities that have different perspectives from our own.”

Much like his first Amazon trip ignited a passion for fieldwork, Griffiths hopes to inspire others who want to make a difference.

Contact Us

Have a UDaily story idea?

Contact us at ocm@udel.edu

Members of the press

Contact us at mediarelations@udel.edu or visit the Media Relations website