Providing closure

Photos courtesy of Project Recover, University of Delaware and Scripps Institution of Oceanography May 25, 2025

UD’s Mark Moline involved in Project Recover’s effort to locate downed B-24 plane in Papua New Guinea

On March 11, 1944, a B-24D Liberator plane from the United States Army Air Forces named Heaven Can Wait was shot down over Hansa Bay in Papua New Guinea. The plane and its 10 crew members were part of a bombing mission against positions at Boram Airfield and Awar Point. When the plane crashed into the bay, several aircraft circled the site in hopes of finding survivors, but none could be found. They have been missing in action (MIA) ever since.

That day forever changed the lives of the families of the 10 crewmen on board. Thanks to the collaborative efforts of individuals and institutions that began in 2017, U.S. Army Air Forces Staff Sgt. Eugene J. Darrigan, one of the 10 crewmembers aboard Heaven Can Wait, was recovered and accounted for on Sept. 20, 2024, providing answers to his family and some comfort to all the families involved.

The recovery efforts included support from the University of Delaware, Scripps Institution of Oceanography, Project Recover, and the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency (DPAA). The family of Second Lieutenant Thomas V. Kelly, Jr., who served as a bombardier aboard the aircraft, was also involved, as Scott Althaus of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, one of Kelly’s relatives, helped complete the search effort and recovery.

The physical recovery was made by DPAA and the U.S. Navy Experimental Diving Unit.

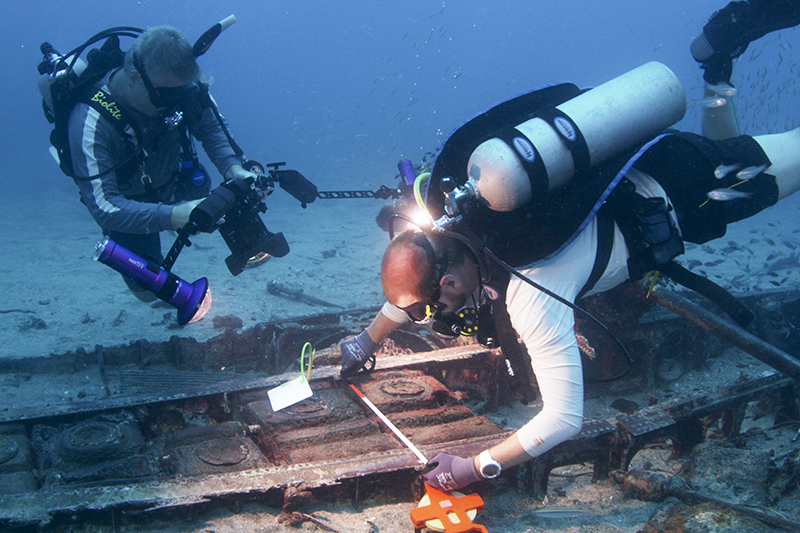

Mark Moline, the Maxwell P. and Mildred H. Harrington professor of marine studies in UD’s School of Marine Science and Policy, was the co-lead of the mission to Papua New Guinea in 2017, which located Heaven Can Wait, with Eric Terrill, director of the Marine Physical Laboratory at Scripps, and Andrew Pietruszka, an underwater archeologist, also at Scripps.

Moline noted that Scripps provided most of the equipment and logistics, which were challenging, as they had to get a large container’s worth of scientific gear to the remote study location.

They landed in Port Moresby, the capital of Papua New Guinea, and boarded a puddle jumper to fly over the Owen Stanley mountain range to Madang, where they then chartered a boat to Hansa Bay to search for the missing WWII aircraft.

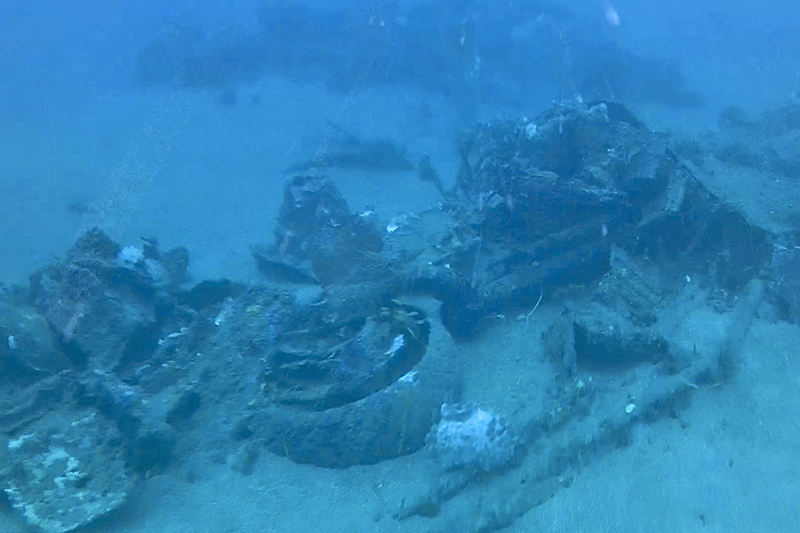

“We spent about 20 days scanning the seafloor, trying to find the five aircraft we targeted for the search,” Moline said. “We had some dramatic pictures of the planes crashing that we used as points of reference. We found pieces of the B-25 from one of the photographs and a P-39, both associated with MIAs. Then, the day before we were supposed to leave, we found the B-24.”

In addition to using the pictures and other historical documents to help them decide where to begin their search, Moline said they also learned from local fishermen.

“If they had fishing poles, they’d mention their gear would get hung up on certain areas,” Moline said. “Some of it was just getting stuck on rocks, but they pointed a little further offshore where we eventually searched, and part of it turned out to be the aircraft.”

Researchers used autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs) to map the seafloor with sonar. When they found what they thought to be part of the aircraft, they launched a tethered Remotely Operated Vehicle (ROV) to confirm that it was the missing B-24.

Family affair

For Moline, the involvement of the crew members’ families set this mission apart from other recovery efforts.

Months before the team was set to leave for their mission, Moline said they were contacted by Althaus about Heaven Can Wait.

“We try not to reach out to families and give people false hope or anything like that, but we wrote back to Althaus and said, ‘This is interesting because we’re actually going there.’ From then on, we involved him in all the activities,” Moline said. “So, we had this meaningful family connection the whole time we were there. When we found the plane, we let him know. Evidently, the families of all the aviators had kept in touch with each other since the accident, which is rare.”

After locating the plane in 2017, Moline, Terrill, Pietruszka and other members of Project Recover went to Minnesota, where they met with members of the Heaven Can Wait families. This was before any of the crew were recovered or identified.

“Eight out of the 10 families were there and they came from all over,” Moline said. “One family called in from New Zealand; a couple drove up from Georgia. The footprint of the people and the families affected by this is amazing. And the fact that we got to know them and that they kept in touch all these years was special.”

Moline said he feels fortunate to be a part of this project and is proud that it has reached the point where crew members are coming home to their families.

“These MIA losses are real national losses,” Moline said. “I put red dots on all the hometowns of these missing airmen, and it covers the whole country. It’s impressive. You get one plane shot down and it affects communities across the United States.”

The interments with military honors for Second Lieutenant Thomas V. Kelly, Jr. and Staff Sgt. Eugene J. Darrigan take place this Memorial Day weekend.

Contact Us

Have a UDaily story idea?

Contact us at ocm@udel.edu

Members of the press

Contact us at mediarelations@udel.edu or visit the Media Relations website