Research on an active volcano

Photos courtesy of Abigail Nalesnik and Kendra Lynn January 30, 2023

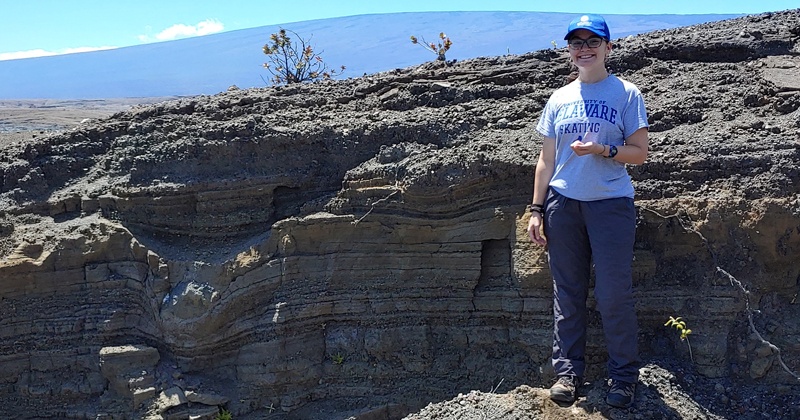

UD doctoral student spends summer in Hawaii studying Kīlauea Volcano

In second grade, Abigail Nalesnik worked on a volcano project for school and said that it kicked off a lifelong love of volcanoes. However, as an undergraduate student at Salisbury University living on the eastern shore of Maryland , Nalesnik wasn’t sure it would be possible to study volcanoes until she started to apply to graduate schools and visited Jessica Warren’s Mantle Processes Group at the University of Delaware.

It just so happened that Warren, associate professor in the Department of Earth Sciences, had a post-doctoral researcher at the time named Kendra J. Lynn, who is now an affiliate associate professor in the Department of Earth Sciences. Warren and Lynn had received a National Science Foundation Grant to conduct geochemistry research of Kīlauea and by working with Lynn and Warren, Nalesnik was able to expand on the original scope of that project and develop a research project looking at physical volcanology — studying the processes and deposits of volcanic eruptions.

That physical volcanology work allowed Nalesnik to travel to the Island of Hawaii and stay in Hawaii Volcanoes National Park to study Kīlauea Volcano, the world’s most active volcano system in September of 2021. In the summer of 2022, Nalesnik was able to return to Hawaii and continue her research.

Nalesnik will present the results of her research during two presentations at the International Association of Volcanology and Chemistry of the Earth’s Interior conference taking place Monday, Jan. 30 through Friday, Feb. 3 in New Zealand.

During the summer, Nalesnik worked in coordination with the United States Geological Survey’s (USGS) Hawaiian Volcano Observatory (HVO), allowing her to continue her collaboration with Lynn, who now works as a research geologist at HVO and is serving as a valuable resource and mentor for Nalesnik on the project.

The first time Nalesnik actually saw a volcano in person was during her fieldwork in 2021.

“All I had been working on up until that point were these little tiny grains that were deposited from Kīlauea,” said Nalesnik. “So walking up that first time, it was incredible. My adviser was telling me some history and background, and I just stood there for a second and it was a very emotional experience.”

Nalesnik’s work involves researching how volcanic tephra deposits — small fragments of rocks — fall around the volcano. Specifically, she is working on prehistoric explosive eruptions of Kīlauea Volcano, which currently features long-lived abundant lava flows, what are known as effusive eruptions, yet has a history of periods with explosive and highly hazardous eruptions.

“These eruptions are orders of magnitude more powerful than any eruption documented since HVO was founded or described after the arrival of Western visitors in the late 18th century,” said Nalesnik. “These periods have been sparsely studied and remain very poorly understood.”

To conduct her research, Nalesnik looks at the geochemistry of tephra-volcanic particles, fragments produced during a volcanic eruption, which range in size from ash to material larger than one meter. Using laboratory equipment at UD, Nalesnik collects the trace element concentrations and then uses models to determine what conditions led to the explosive eruptions.

“I am also using physical volcanology to understand eruption intensity and what kinds of hazards we may anticipate for modern-day Hawaii,” said Nalesnik. “An explosive eruption happening today would have devastating effects on human health, the livestock and agriculture industry, the island economy, and air traffic.”

In 2021, she spent a total of five weeks conducting research at five different field sites. She said that looking at where a deposit is located can help determine everything from how large a volcanic eruption was to which direction the wind was moving when a certain piece of tephra was deposited.

“Looking at where the deposit is, it’s not all preserved equally and it wasn’t all deposited equally,” said Nalesnik. “We’re thinking about its likely source area and the eruption that produced it, but then also how the wind may have influenced where the plume spread material. We look at the deposit color, thickness, grain size, and componentry to understand what type of eruption made it. The actual componentry can tell us if it is made from the juvenile volcanic material or if it’s from the lithic bedrock.”

Nalesnik continued her work during the summer of 2022, looking at the volcanic deposits, and as Kīlauea is an active volcano, she concedes that it can be a bit of a humbling experience. Last fall, two days before she flew out at the end of fieldwork, she got to witness an eruption of Kīlauea Volcano firsthand.

While working with a team of scientists from HVO, they got an alert of an earthquake swarm right under the summit of the volcano — which can be indicative of magma movement — and the team wanted to put out some sample containers just in case the earthquake swarm meant that an eruption was going to happen.

“Driving out, I’ll never forget this white plume coming out of Halema’uma’u Crater. I thought to myself, ‘Oh my gosh, it’s happening,’” said Nalesnik.

Having done all the necessary safety certifications with HVO, Nalesnik and the research team were able to grab gas masks, helmets, and all of their gear to head straight back to the national park to monitor the eruption.

“I wanted to go see the fresh lava, but I knew collecting samples was important because the wind had already started to blow them away. So we carefully collected samples and then went over to the lava lake,” said Nalesnik. “I’ll never forget the smells and the sounds. It smelled a lot like sulfur, that rotten egg smell, but the sound of it was like a very heavy water fountain. You could see the molten material bubbling up in small fiery fountains all over the lava lake and it gave me a greater appreciation for the people who live in this area and also the cultural significance that Kīlauea has. It was breathtaking.”

You can read more about her experience at the eruption in UD’s Research magazine.

For that eruption, Nalesnik and the other scientists collected many pieces of tephra — which were cool and completely fine to touch. These samples will be used to look at the initial conditions and chemistry of the eruption. It taught Nalesnik the importance of respecting the power of volcanoes.

“The volcanoes in Hawaii are protected and it is very important to respect the boundaries that the national park service has implemented,” said Nalesnik, who noted that in other locations around the world, she’s seen videos of people simply walking right up to an erupting volcano. “There are fences and boundaries set up to create space away from volcanic hazards that pose a significant threat to human health and safety. It can be very unfortunate when someone doesn’t follow those rules.”

As for any advice she would give to students interested in studying volcanoes, Nalesnik said there is a wealth of information available from geology courses, books, and documentaries, to scientists on social media, where students can see what scientists do during their day-to-day routines.

Nalesnik also stressed that it is important to understand how diverse volcano research can be — from seismic activity to geochemistry — and that aspiring volcanologists should take as many geology classes as possible.

“Those students who see the most rocks are going to win,” said Nalesnik. “They always have that larger pool of knowledge that is applicable to broad, sometimes complex concepts that help them understand the wider realm of earth science and get them into volcano science.”

Contact Us

Have a UDaily story idea?

Contact us at ocm@udel.edu

Members of the press

Contact us at 302-831-NEWS or visit the Media Relations website