Solitary confinement

Photo illustration by Jeffrey C. Chase February 24, 2023

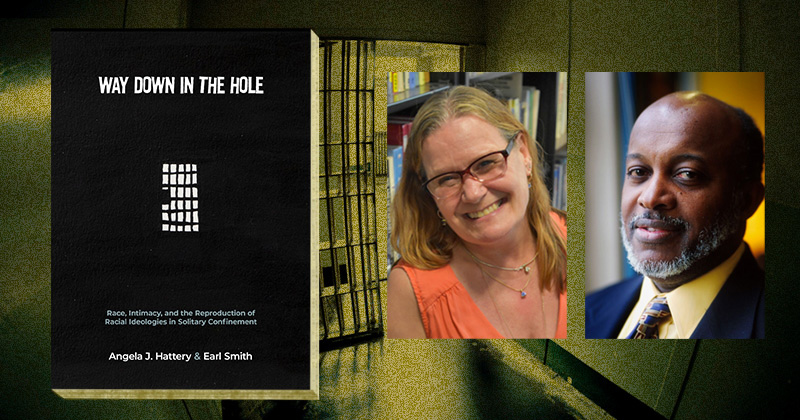

UD professors’ research shows U.S. prison system can perpetuate racism

During the peaks of the COVID-19 pandemic the term "solitary confinement" was often tossed around as a way to complain about the mandatory periods of isolation in our homes.

Among those cringing after the term was used this way were University of Delaware Professors Angela Hattery and Earl Smith.

Real solitary confinement is in small cells, rarely larger than 6 feet by 8 feet, with little or no natural light. In the cells are nothing but one’s thoughts, a toilet, a bed and a single book – usually a Bible. The prisoners are locked in for 23 hours a day with the possibility of 1-hour out of cell for recreation, depending on staffing situations, noted Smith.

Smith and Hattery are professors in the Department of Women and Gender Studies, located in the College of Arts and Sciences. Their research is focused on systemic racism and gender-based violence. Hattery is also co-director of the Center for the Study and Prevention of Gender-Based Violence.

The pair recently published a book, Way Down in the Hole: Race, Intimacy, and the Reproduction of Racial Ideologies in Solitary Confinement, which is based on hundreds of hours of observation in solitary confinement situations and interviews with nearly 100 people who are incarcerated or work there. Their research documents the torture of solitary confinement and uncovers the role it plays in perpetuating systems of racism and white supremacy across America.

“Most Americans believe that the torture that takes place in solitary confinement is in Russia, is in North Korea, is in China,” Hattery said. “It never occurs to them that somewhere between 50,000 and 80,000 people in the United States are locked in solitary confinement every single day. We are torturing that many people every single day in solitary confinement.”

Over the course of three summers (2017-2019) Smith and Hattery conducted research inside solitary confinement units in a mid Atlantic state. In exchange for unprecedented access to the solitary confinement units, the pair agreed to not release the exact location of the prison they visited.

“Solitary confinement is a place where our racial history is on full display,” Hattery and Smith wrote. “Not only are the majority of the staff white and the majority of the prisoners Black and brown, but the very premise of solitary confinement relies on the foundation of white supremacy on which this country was built.”

The book illuminates the issue of white racial resentment and how it can form and grow within solitary confinement. Prisons with solitary confinement units are often located in rural communities that are economically disadvantaged and predominately white. Most interactions these white guards have with Black people are in cells.

“As a result, the stereotypes they have of Black people, as violent, angry, drug-using criminals is reinforced,” wrote the two sociologists. “In solitary confinement, where the correctional officers are required to hand deliver all of the necessities of daily life, including food, medicine, and even toilet paper, they come to resent the ‘benefits’ that they perceive the prisoners are receiving, including access to medical and mental health care that they have trouble getting for themselves and their families.”

The lasting impacts of solitary confinement

The United Nations defines 15 consecutive days in solitary confinement as torture. After 24 hours, prisoners start exhibiting anxiety and depression, Hattery said. As their research shows, many prisoners spend months or years in solitary confinement.

“The majority of people who go to prison, and more so the majority of people we lock in solitary confinement will be released from prison one day. They will come home and live in your neighborhood, your community, they will work in the stores and restaurants you frequent,” Hattery said. “They will be around your kids. And, they will bring with them the unhealed trauma of their time in solitary confinement, which often means they will be more prone to engage in violence that will ultimately harm you.”

In solitary confinement prisoners lose many liberties available to them, including communication from the outside world, and their ability to make decisions for themselves declines, all of which makes it harder for them to function when they do eventually get released from prison, their research shows.

“There are only a tiny number of instances in which solitary confinement is appropriate, and even then, it should never be used for more than a day or two at a time,” Smith said.

Contact Us

Have a UDaily story idea?

Contact us at ocm@udel.edu

Members of the press

Contact us at 302-831-NEWS or visit the Media Relations website