Investigating Parsons Island

Photos courtesy of Michael O’Neal November 05, 2020

UD grad student and research team investigates archeology, geology of Chesapeake Bay island

Neeshell Bradley-Lewis was completing an undergraduate double major in both archaeology and geology at Appalachian State University when she met Michael O’Neal, a professor in the University of Delaware’s Department of Earth Sciences, at the 2018 Geological Society of America conference. O’Neal had earned a degree in archaeology before completing his doctorate in geology, and he let Bradley-Lewis know that she could pursue a master’s degree at UD that would combine both of her passions. Bradley-Lewis jumped at the opportunity.

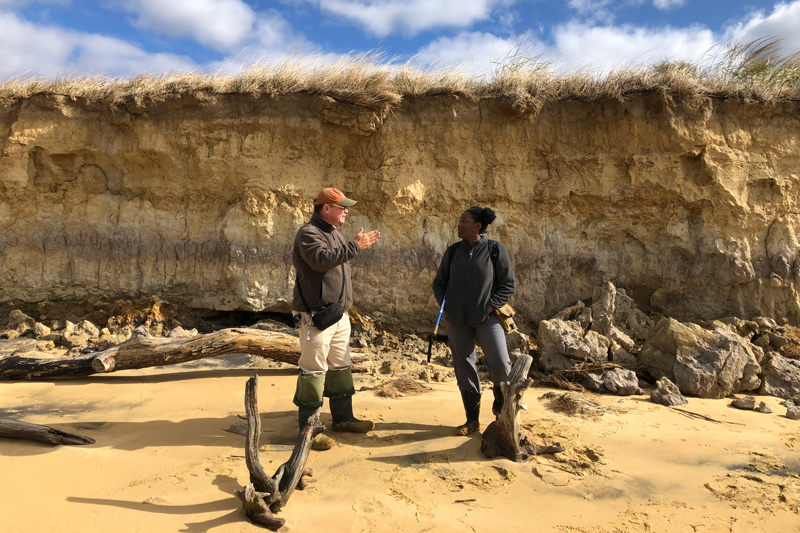

Now entering her second year at UD, Bradley-Lewis combines her love of archaeology with her love of geology by conducting research on Parsons Island in the Chesapeake Bay. On Parsons Island, she works with O’Neal and Darrin Lowery, a geologist and an affiliated professor at UD, who also works as a research associate in archeology at the Smithsonian. Lowery earned his doctorate from UD in 2010, having studied with O’Neal while combining geology and archeology much as Bradley-Lewis is doing today.

“I was joking that when the three of us were standing on the island, I don’t know if there’s ever been that many people who have degrees in archaeology and geology standing in the same place at the same time doing the same project,” said O’Neal. “It is unique to have people who find the cultural side and the artifacts fascinating and also realize that if you’re digging in the earth but you don’t understand the geology as well, you’re really only getting half the story.”

Research focus on the island

Parson’s Island is an unusual site that can provide important information to the regional record. Bradley-Lewis, O’Neal and Lowery are interested in researching two key approaches, one archaeological and one geological.

Archaeologically speaking, excavations on the island have uncovered artifacts that date to around 20,000 years ago, a period of time during the most recent part of the Pleistocene Epoch, when ice covered much of North America and it is thought that there wasn’t much human activity happening on the East Coast.

Bradley-Lewis is digging a pit on the island about a meter and a half below the surface that already has produced dozens of artifacts, with plans to start digging another pit in the near future.

While a lot of these artifacts — about 100 in total — have been found closer to the surface in soil that dates around 13,000 years old, the hole that Bradley-Lewis is examining has a soil profile of around 20,000 to 24,000 years old.

“We’re essentially digging into the ground nearly two meters deep to find those artifacts in place. Most of the time you see them, they are eroded out of a bank but that doesn’t really give you that much meaning,” said Bradley-Lewis. “We’re trying to find them in the ground in place and then hopefully find something to date so that we can attach an age to them.”

The geological interest comes from the stratigraphy, a branch of geology concerned with the study of rock layers, on the island offers a window into what was happening in the Delmarva region during the late Pleistocene.

O’Neal and Lowery said that the area is kind of a Rosetta Stone of the late Pleistocene geology, and they will get a lot of mileage out of setting up the site as an example of what that stratigraphy looks like.

The research team has kept moving forward, even during the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic. Because their research is so isolated, O’Neal explained that they are able to stay socially distant while conducting their research on the island.

The team uses Ground Penetrating Radar (GPR) to map the stratigraphy of the subsurface, which gives them an idea of what’s hidden beneath the island’s surface. The GPR uses imagery to reflect the changes of the underlying stratigraphy at different intensities, and that also helps the researchers look for buried surfaces and anomalies that could have cultural meaning.

“The main part of Parsons Island is kind of up from the sea level and then there’s a steep embankment that has really interesting stratigraphy with at least four ancient soils,” said Bradley-Lewis. “Another goal of ours is to look at the changing stratigraphy around the entire island because in such a small area, it changes four or five times, which is not something you typically see in such a small, compact region.”

Bradley-Lewis said that getting the opportunity to conduct research on the island has expanded her skill set, particularly when it comes to studying the geomorphology of the island. She also said that she enjoyed being able to jump right into research as a graduate student at UD.

“Mike (O’Neal) had some research options available and laid them out and said, ‘Pick what you like,’ ” said Bradley-Lewis. “It was pretty soon that we first went out to Parsons and I said, ‘This is the one.’ And we really haven’t stopped the research since.”

Contact Us

Have a UDaily story idea?

Contact us at ocm@udel.edu

Members of the press

Contact us at 302-831-NEWS or visit the Media Relations website