UD research in Antarctica

Photos courtesy of Katherine Hudson March 09, 2020

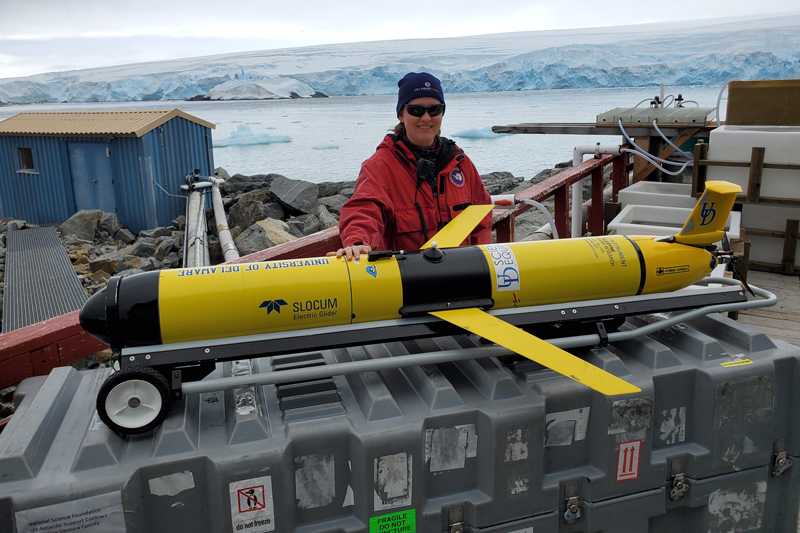

UD’s Matt Oliver and Katherine Hudson conduct research in Antarctica’s Palmer Deep Canyon

The University of Delaware’s Matt Oliver, the Patricia and Charles Robertson Professor of Marine Science and Policy, and Katherine Hudson, a UD doctoral candidate and a Patricia and Charles Robertson Fellow, spent the winter in Antarctica, conducting research at Palmer Deep Canyon while living at Palmer Station, located on Anvers Island in the Antarctic Peninsula. The two researchers will be in Antarctica until March working as part of Project SWARM, a multi-institutional research group of ocean scientists looking at the physical mechanisms driving food webs focusing in Antarctic biological hotspots. Oliver and Hudson recently spoke about their time conducting research in such a remote part of the world.

Q: Could you talk about the research you are conducting in Antarctica?

Katherine Hudson: We are researching how the physical oceanography — the currents, tides, etc. — builds the food web within the biological hotspot within Palmer Deep Canyon. We hypothesize that the physical oceanography plays a large role in bringing krill, an important food source for local predators, into the system. While Matt and the rest of the Project SWARM team are focusing primarily on surface and near-surface processes, my dissertation will focus on how subsurface processes may be impacting the hotspot.

Matt Oliver: One useful metaphor is a farm vs. grocery store approach. We are trying to find out whether the biological hotspot at Palmer Deep Canyon operates more like a farm, where food is locally produced, or if it operates more like a grocery store in a city or a town that needs food delivered from far-away places. The “food” that is being transported or locally produced in this instance are krill and the “customers” are the Adelie penguins and the Gentoo penguins that inhabit the biological hotspot of Palmer Deep Canyon.

Q: How does this research build off of previous research efforts?

Katherine Hudson: Project SWARM builds off previous work from the 2015 field season at Palmer Station, known as Project CONVERGE. Project CONVERGE had similar goals, focusing on how the physics affect predator behavior. While near-shore krill distributions were studied in CONVERGE, they were not examined offshore where the other technologies were deployed. Therefore, Project SWARM builds upon this work by adding the focus on the krill distributions in the same time and space as the other technologies that we are deploying to get a better understanding of how the physics may be affecting the distribution of this important resource. Many, if not all, of the questions that the SWARM team is focusing on, and many of the questions I am asking in my dissertation, are built off the data collected from the technologies deployed during CONVERGE.

Matt Oliver: Also, a big addition to SWARM is the use of an ocean model. The ocean model will allow us to take what we learned here at Palmer, and apply it to other locations in the West Antarctic Peninsula (WAP). We can examine and understand the hot-spot phenomena up and down the WAP. As has been covered in the news, the WAP is changing quickly. We want to know how these hotspots work, how resilient they are to climate change, and therefore understand other hotspots worldwide.

Q: What are some of the challenges with conducting research in such a remote region?

Katherine Hudson: Conducting research in Antarctica requires a lot of planning ahead of time. The gliders were shipped to California in July to arrive in Antarctica in early December. We had to prepare all of the tools for the gliders in June and in early July, and that includes packing extras of everything just in case something goes wrong. Some of the new technologies also needed to be tested or calibrated beforehand. Also, there is no hardware store in Antarctica, at least not at Palmer Station. Therefore, there are limited to no spare parts available if you need more bolts or O-rings, so you have to pack all of the spares you think you will need as well.

Q: Katherine, what has it been like getting to conduct research in Antarctica for the first time?

Katherine Hudson: Conducting research in Antarctica has been a life changing experience. I already know that I would love to return to Antarctica to do research with the Long-Term Ecological Research (LTER) program, or even my own research in the future. I was surprised that the community at Palmer is very tightly knit. Everyone from the scientists to the support staff are so supportive of everything that everyone else is doing. It is just like science nerd camp and I love it!

Q: How does this experience differ from previous research experiences you’ve participated in?

Katherine Hudson: This is definitely the most remote research experience I have participated in. I previously did a Research Experience for Undergraduates (REU) at the Bermuda Institute for Ocean Sciences during my undergrad. I was able to get a small scholarship to extend my internship for an extra month, so I was there for about the same length of time that I will be in Antarctica. However, we always had access to fresh food and enough internet to stream Netflix. Here at Palmer, fresh food (or freshies) only come down on the ship every month or so. Some things like potatoes and onions last a long time, but fresh greens do not last very long. We also have an extensive movie library to access at Palmer instead of streaming movies. We were able to stream the Super Bowl but that basically drains all the bandwidth for everyone else, so things like that need to be very strategic and planned across the station.

Q: Was there anything you did beforehand to prepare yourself for the experience?

Katherine Hudson: To prepare myself (other than studying for my qualification exams), I had to get into shape. A lot of the work down here involves manual labor and moving heavy equipment onto and off of boats, so being in enough shape to lift properly is key. We are a long way from help if you seriously injure yourself so there is a big emphasis on being safe at all times, not just when lifting things.

Q: What has been the most memorable aspect of getting to participate in this research?

Katherine Hudson: The most memorable aspect of being able to participate in Project SWARM is actually coming to Antarctica. Antarctica, and specifically the area around Palmer Station, is a really special place, both for the oceanography and the station life, and I am really thankful that I got to participate in research here with a fantastic group. It was also really beneficial for me to be able to come here and work in a place that I have read about and published data on. Being at Palmer Station has given me a new perspective on all of my reading and my previous work.

Contact Us

Have a UDaily story idea?

Contact us at ocm@udel.edu

Members of the press

Contact us at 302-831-NEWS or visit the Media Relations website