African American suffragists

Photo illustration by Jeffrey C. Chase | Photos by and courtesy of Evan Krape, Carol A. Scott, H. Gordon Flemming, Delaware Public Archives, Delaware Historical Society, iStock August 17, 2020

UD students and professor research and celebrate those forgotten in the push to give women the right to vote in 1920

Search the recesses of your brain for grainy, black-and-white photos from the pages of your high school history textbook. Specifically, call up all the grainy, black-and-white photos pertaining to women’s suffrage. The images you conjure likely depict militant white women being arrested. Or militant white women picketing outside the White House. Or militant white women burning the speeches of President Woodrow Wilson, a man deemed hypocritical for extolling the virtues of democracy while an entire gender remained disenfranchised.

These images are real. And they’re dramatic. And they illustrate a radical political activism that has inspired authors and poets and filmmakers for 100 years. But they’re also something else: Incomplete.

Or, as Anne Boylan, professor emerita of both history and women and gender studies at University of Delaware, put it: “In movies about the struggle for votes for women, a lot gets left on the cutting room floor.”

This is one of the takeaways from an ongoing project Boylan undertook in 2016. That year, Tom Dublin, a peer from Binghamton University in New York, reached out to the social historian. In anticipation of the 2020 centennial anniversary of the 19th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which guaranteed women the right to vote, Dublin had begun a crowd-sourcing initiative that, with the help of researchers nationwide, set out to produce more than 3,500 biographical sketches illuminating the work of grassroots suffragists. (In America, activists preferred this spelling instead of the British “suffragette.” Because of that “ette” suffix, meaning small or diminutive, this term was often deployed in a derogatory way by those opposed to the movement.) This compilation, still in progress, tells the stories of all the suffrage leaders we learned about in junior high. But, critically, it also includes the activists forgotten by history — namely, African American suffragists.

“Women’s history has always been suppressed,” Boylan said. “It hasn’t been accorded the same importance. And this is especially true for women of color. That’s why projects like this are so crucial. Without them, these stories just disappear.” (March is Women’s History Month.)

![Library-Scholar_Series-Delaware_Suffrage_Leaders-021220 Anne M. Boylan, professor emerita of history, presenting a "Scholar in the Library Series" talk titled "Finding Delaware's Women Suffrage Leaders in the Archives." The talk centered on "the archival sleuthing involved in researching and writing biographies on more than 60 Delaware suffrage leaders across a wide array of backgrounds." [Events Calendar]

Pictured: Anne Boylan, professor emerita of history.](/udaily/2020/march/Anne-Boylan-Delaware-suffragists-African-American-votes-for-women-centennial-Nineteenth-Amendment/_jcr_content/par_col_8_udel/image_175806430.coreimg.jpeg/1583181258160/21-anne-boylan-library-scholar-series-delaware-suffrage-leaders-021220-021-800x533.jpeg)

Despite being on the cusp of retirement, Boylan agreed to serve as the project’s Delaware coordinator. She partnered with local researchers, elementary school teachers and their students, as well as five student collaborators from a UD course on the history of African American women. She worked as editor and fact checker, while the students researched and wrote. They began by digging into seven names Dublin had passed on.

“I thought: How long could it possibly take to come up with seven biographies?” Boylan said. “Well, five years later, we’re up to 60-plus suffragists.”

Using a variety of resources — including digitized newspapers, live interviews with the descendants of their subjects, and the Ancestry genealogical site available at UD’s Morris Library — the group pieced together a more complete picture of the Delaware suffrage movement and its agitators.

For starters, this was a far more diverse movement than your typical school curriculum would have you believe. It comprised Jewish, Catholic and Unitarian members. Working class and elite members. Natural born and naturalized citizen members. And, importantly, white and African American members.

“These weren’t delicate or naive women,” said Boylan, who wrote a book on this research called Votes for Delaware Women, forthcoming from the University of Delaware Press. “These were women who got things done.”

Boylan estimates about 20 percent of suffrage leaders in this state were Black. You won’t see them in photos, because the more confrontational tactics that made for front-page news were risky business for women of color, who were subject to racist abuse from onlookers. Instead, like most suffragists of any race, these women were largely focused on the less sensational — though equally important — work of petitioning, lobbying and organizing.

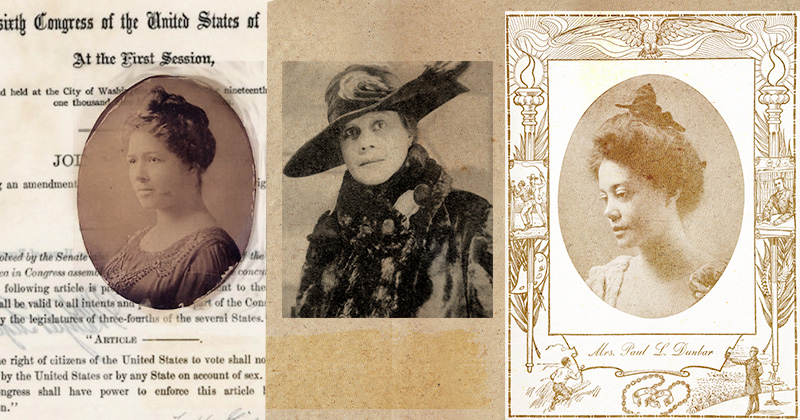

Of the three suffrage organizations in Delaware, one — the Equal Suffrage Study Club — was founded by and for Black women. A leader was Alice Ruth Moore Dunbar (later Dunbar-Nelson), the influential poet and journalist whose papers, housed at Morris Library, have attracted scholars from around the world. Lesser-known members included Emma Gibson Sykes, a choir director and charter member of the Wilmington branch of the NAACP, and Bessie Spence Dorrell, a music teacher who fought for justice even after her first child died and her husband was committed for insanity.

Then there was Blache Williams Stubbs, a teacher at Wilmington’s Howard School, the only high school in the state at the time with a four-year curriculum for Black students. A mother of three, she co-founded and directed a community space in Wilmington that offered education and recreation to African Americans. Meetings here, presided over by Stubbs, resulted in the development of the Delaware Federation of Colored Women’s Clubs, focused on improving opportunities for African American youth. When the first mass suffrage parade in Delaware kicked off in 1914, Stubbs led a so-called colored section through the streets of Wilmington. She also hosted lectures on equality, fought segregation in public spaces, and served as state chairman of the Black-led National Republican Women’s Auxiliary Committee. Today, a school in Wilmington bears her name.

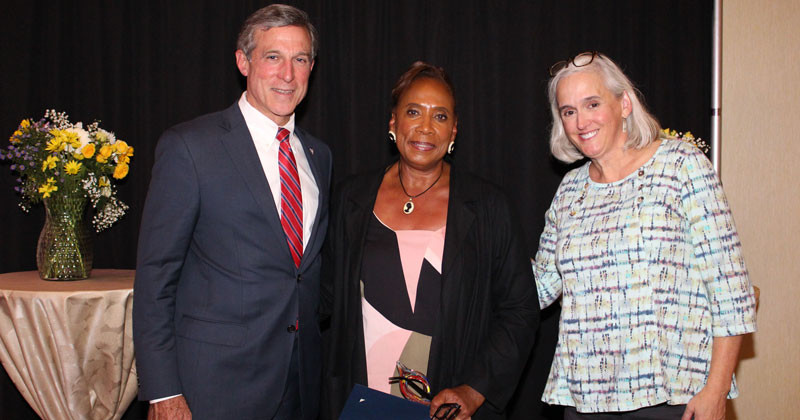

“When you look at the state of politics today and the impact that not just women but Black women are having on a changing political climate, you realize these activists were the groundbreakers,” said Carol A. Scott, a junior studying Africana studies and Spanish. Her biography of Stubbs led to the suffragist’s induction, out of 65 submissions, in the Delaware Women’s Hall of Fame. “I would like young people today to know not just Martin Luther King and Malcolm X and all these other famous people, but the other folks — sheroes, or female heroes — from right in their own communities.”

Like all suffragists, Black activists in Delaware were forced to cope with a long and often frustrating battle for the vote — the first failed attempt at changing the state constitution happened in 1897. But these women faced an additional roadblock, too.

“There was the looming shadow of white women’s racism,” Boylan said. “When dealing with racist lawmakers in Delaware, there was an unwillingness from white suffragists to say: ‘We’re seeking votes for all women.’ They tended to not touch the issue. To deflect. It’s a different strategy from shouting racist slurs, but it still means the marginalization of African Americans.”

In 1920, Delaware had the opportunity to become the 36th — and final — state needed to ratify the 19th Amendment, ensuring it’s passage. The legislature voted it down, and Tennessee went on to become that final state, guaranteeing voting rights for all women in America. For those wanting to learn more about the forgotten luminaries who mounted this campaign for suffrage, the biographies written by UD students and other researchers can now be accessed via the Online Biographical Dictionary of the Woman Suffrage Movement in the United States. The sketches written by UD students about some of the state’s Black suffragists, specifically, have also been published in the most recent edition of the biannual journal of the Delaware Historical Society.

According to these researchers, this history can sometimes feel like a million years ago. Other days, it doesn’t feel like history at all.

“On the one hand, I think: ‘Yes, an awful lot has changed since this time,’ ” said Boylan, who has curated the “Votes for Delaware Women” exhibition on display now at Morris Library. “But on the other hand, much has remained the same. It’s amazing — we are still discussing who is able to exercise their voting rights, 100 years later.”

This is exactly the reason projects like this, she added, are so important.

“They teach us to be vigilant,” Boylan said. “Rights won can be lost. And there must be a constant effort to maintain them.”

Contact Us

Have a UDaily story idea?

Contact us at ocm@udel.edu

Members of the press

Contact us at 302-831-NEWS or visit the Media Relations website