UD helps downtrodden oysters make a comeback

December 02, 2020

You have to feel a touch of pity for the poor little Delaware oyster—so dutiful and efficient, so tasty and briny, yet still so deeply despised by many a squeamish diner.

Even oyster fans find it hard to envy the bivalve’s grimexistence: Year after year, through lashing snow squalls and roasting summers, they squat gracelessly in the murk of some tide-ruff led bay, hoovering bits of passing plankton.

There they sit, and eat and eat, disinclined to budge until the day they are snatched from bed, plopped onto a plate, and swallowed whole—preferably with a touch of lemon and a frosty ale.

But there is glory in their naked sacrifice, and a brilliance to their brainless form.

The humble oyster sustains us, in so many ways. During its stay in the bay, just one oyster can filter thousands of gallons of nutrient-choked water, boosting an ecology that has long been desperate for a good scrubbing. Nearby, other species and even the surrounding aquatic vegetation grow healthier in its presence. And even after being unceremoniously hauled to land, the oyster will attract a gaggle of admirers—seafood purveyors, worshipful chefs, ravenous diners—who rejoice at its homely beauty, and profit from its bounty.

In a way, these gender-fluid, facelessly forlorn critters stand as the unspoken heroes of a story that emblemizes Delaware’s ecosystem, embraces its past and now offers a ray of hope for its future. That’s certainly the way Ed Hale and his team see it.

For the past couple of years, the 35-year-old marine advisory specialist and his Delaware Sea Grant colleagues have been waging a waterborne, grassroots campaign to revive Delaware’s oyster, once adored by bivalve slurpers up and down the coast—until nearly disappearing in the face of human despoilment, greedy harvesting and insidious diseases.

With the help of special-built cages and no small amount of scientific savvy, Hale and his team are aiming to bring those good old days back. This time, they hope it’s for keeps. So do the communities along the coast, where memories still live of the days when wild oysters filled these waters—layering Delaware Bay and its brackish backwaters, providing the mountains of crushed shells that once paved Southern Delaware driveways, and filling the bushel baskets that fed so many struggling families.

“There were millions of bushels harvested in the late 1800s,” mostly out of the Delaware Bay by boats heading out from Leipsic, Port Mahon and New Jersey,” says Hale, EOE12PhD. “It was a monster fishery that supplied Wilmington and Philadelphia with a lot of oysters.”

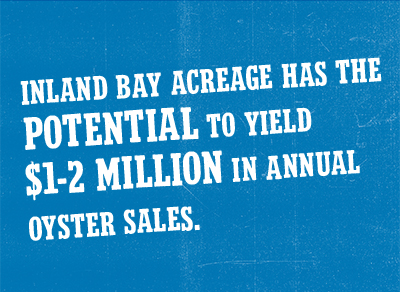

For years now, Delaware has stood as the only East Coast state without a well-established oyster aquaculture fishery, even as the wild oyster struggled to endure. Prospects brightened when the state loosened restrictions in 2017, opening access to enough Inland Bay acreage to potentially yield $1-$2 million in annual oyster sales, create 100 full-time jobs and filter 20-48% percent of the bays’ water each day.

The Delaware Sea Grant College Program, a federal initiative based at UD, has stood behind the farmers the whole time, lending its support and encouragement to fledgling businesses, gauging the preferences of finicky consumers, and even serving as an unofficial market-maker between farmer and consumer. Oyster efforts are rooted in Delaware SeaGrant’s longtime mission: To promote the wise use and conservation of marine and coastal resources through research, education and outreach activities that benefit the public and the environment.

Today, there are six UD-supported farmers and growing operations—from retired engineers to former schoolteachers—who motor day after day to their plots staked out on Delaware’s broad Inland Bays. Already, a handful of commercial enterprises have been born: Delaware Cultured Seafood’s “Delaware Salts” are gaining some local fame, and the Rehoboth Bay Oyster Co.’s beauties are bagged up and ready to slurp at its recently opened Rehoboth Beach store.

“We’ve definitely seen an increase in farmed oysters from Delaware being available at restaurants from Hockessin to Dewey Beach,” Hale says. “My sister actually saw them in New Jersey, so they’ve been going out of state as well.”

Thanks to UD, the potential allure has been systematically assessed: In Sea Grant-funded research, UD marketing scholar Kent Messer has found that 28% of Delaware consumers say they would pay a higher price for a local product that’s branded with a Delaware “Inland Bays Oysters” logo.

“The farmers took a lot of lessons from that marketing study,” Hale says. “They’re kind of running with it now.”

And there’s also the Delaware oyster’s most important asset: A taste perfectly suited to today’s preference for smaller, brinier oysters. “It’s not as metallic tasting as some oysters can be, and they have a bold upfront, salty finish,” Hale says.

Yet it still has been a choppy journey, one vulnerable to evolving ecosystems, unpredictable markets and well-entrenched competition—even before the pandemic so rudely interrupted. “The bigger outfits in Virginia and Maryland are just ahead in the game, and they know what to do,” Hale says. “So, you have high competition, and a steep learning curve—you need about a $50,000 initial investment just to get started.”

Some of farmers’ basic training comes free, courtesy of Sea Grant forums that are laced with a helpful dose of reality: It can take two years before the first harvest is ready, and farmers must devote at least three days each week tending their crop, repeatedly hauling out the young oysters to be scrubbed, tumbled and pruned of algae. “On five acres, they can make money, but profit margins are function of work input,” Hale says.

Former postal worker Steve Friend and his wife, Shelia, can tell you all about that. As the Lewes-raised son of a devoted amateur clammer, he caught the oyster farming bug after enduring one-too-many “honey-dos” after retirement. But the most compelling motivation was the grim statistics he read about Delaware’s rivers and streams, still so polluted that just 15% are fit for swimming.

“That really hit me in my heart,” says the Georgetown resident, who tends a crop of 275,000 Rehoboth Bay oysters. “I asked myself, ‘What can I do to help clean it up?’ I was the fourth person that got a permit and the third person that got oysters in the water. It’s hard, but I think it’s worth it in the long run.

“Now the state needs to do more to get the word out—that we grow oysters here.”

He and Shelia regularly hit the roads of Delaware, popping into restaurants to hand out business cards and offer free tastings. “You know how many responses I got from people? Zero. Where are all the people who say they want to ‘buy local’? It’s like they’re afraid of them.”

That’s the kind of dry-land challenge Delaware Sea Grant has been doing a lot to help with, he says. Turning his expertise in experimental economics toward the problem, Messer found that a solid subset of consumers are willing to pay more for “local” oysters. And while infrequent oyster consumers were drawn to oysters labeled as “wild-caught,” experienced oyster consumers preferred oysters raised via aquaculture, Messer discovered.

Ultimately, the effort gave rise to a splashy logo and tagline, aiming to enhance Delaware’s visibility. “It’s colorful and it makes an impact. The tagline—a Southern Delaware Delicacy—really resonated,” Messer said.

The oyster’s still-unrealized potential should be enough to encourage legislators to support further expansion, Messer believes. In the meantime, UD researchers are continuing their push, working to identify additional suitable species, exploring ways to “purge” oysters of any contaminants, and taking steps to expand aquaculture into the Delaware Bay.

But the biggest challenge—to the farmers, to Delaware Sea Grant and to UD itself—has been the ongoing economic malaise brought on by the pandemic. “Most of our farmers were still developing their initial crop of oysters when COVID hit,” Hale says. “Now, they’re facing a wall, asking, ‘Where do I go with my oysters?’ This is the next hurdle for them in the business venture.”

Contact Us

Have a UDaily story idea?

Contact us at ocm@udel.edu

Members of the press

Contact us at 302-831-NEWS or visit the Media Relations website