Portrait of an exceptional woman

December 02, 2020

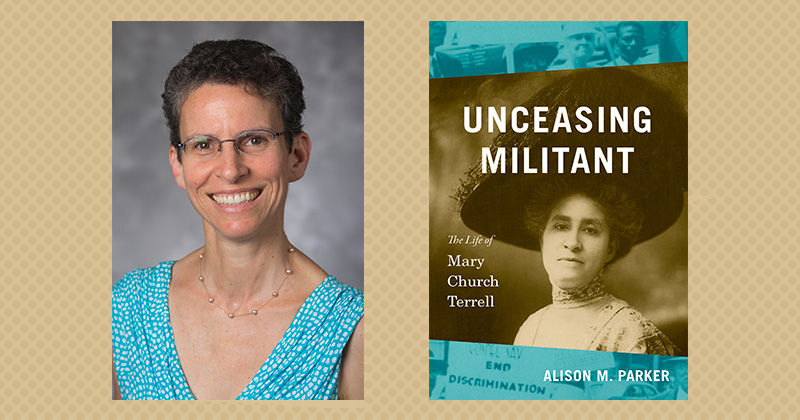

New book profiles key civil rights activist Mary Church Terrell

When University of Delaware historian Alison Parker was researching activists of the 19th century for a book she wrote in 2010 on women’s political thought, she couldn’t believe that there was no biography of one of the most exceptional of those activists—Mary Church Terrell.

“I was really intrigued by her story, and amazed that no one had written it,” said Parker, who is Richards Professor of American History and chair of UD’s history department. “The first leader of a national Black organization, the National Association of Colored Women, and a co-founder of the NAACP, credited with establishing Black History Day to commemorate Frederick Douglass … she was a civil rights activist her whole life.”

Once Parker finished her book on women’s political thought, she began focusing on Terrell. The result is a new book, Unceasing Militant: The Life of Mary Church Terrell, published this month by the University of North Carolina Press.

Parker connected with descendants of Terrell, who showed her items that had belonged to her and had been kept in a storage locker. They provided a wealth of information about Terrell’s remarkable life, including letters and diaries never before studied by historians. Parker also helped Terrell’s family arrange for the donation of her possessions to the National Museum of African American History and Culture. In addition, Oberlin College has accepted Terrell’s papers for its archives and is planning a digital history project.

“Unlike research topics where you worry about a lack of material, in this case, there’s almost too much material—she saved every scrap of paper,” Parker said of Terrell. “She had an awareness of history, and she knew that she had a story to tell.”

And it’s quite a story. Born into slavery in Tennessee during the Civil war, Terrell had two white grandfathers, and those biological ties meant that her family was better positioned economically when slavery ended, Parker said.

Her father, Robert Church, owned a saloon and became wealthy after buying up properties that white owners abandoned in Memphis when they fled the city during the 1878 yellow fever epidemic. He used his money to build up a neighborhood known as Beale Street, the birthplace of the blues, and was known as the first Black millionaire in the South. Terrell’s mother owned a hair salon whose customers were white women.

Terrell’s life was filled with pioneering accomplishments. She earned a four-year degree at Oberlin College—a program known as a “gentleman’s course” because most women pursued two-year degrees—and became a teacher in Washington, D.C. She became an anti-lynching activist and in 1896 was the first president of the new National Association of Colored Women’s Clubs, which focused on suffrage and civil rights, making her the first leader of any national Black organization.

“Her life gives a fascinating window into the way affluent African Americans used their resources to take on activist causes,” Parker said.

Parker’s work on Terrell, who was a suffragist who picketed the White House with the National Woman’s Party, has gained attention, especially as America marked two milestone anniversaries in 2020, the centennial of the 19th Amendment allowing certain women the vote, and the 150th anniversary of the 15th Amendment, allowing non-white men the vote.

Although the coronavirus pandemic has limited the kinds of in-person lectures and events in which Parker was often participating, she said interest in Terrell has remained high. Her research has always focused on the intersection of race and gender, and Terrell’s life and work provide an important example of that, she said. Terrell is being inducted into the National Women’s Hall of Fame in a virtual event on Dec. 10, with Angela Davis serving as master of ceremonies.

In a review of Unceasing Militant, historian Anastasia Curwood called the book “a wonderful biography of a foundational figure in the history of U.S. civil rights.”

Contact Us

Have a UDaily story idea?

Contact us at ocm@udel.edu

Members of the press

Contact us at 302-831-NEWS or visit the Media Relations website