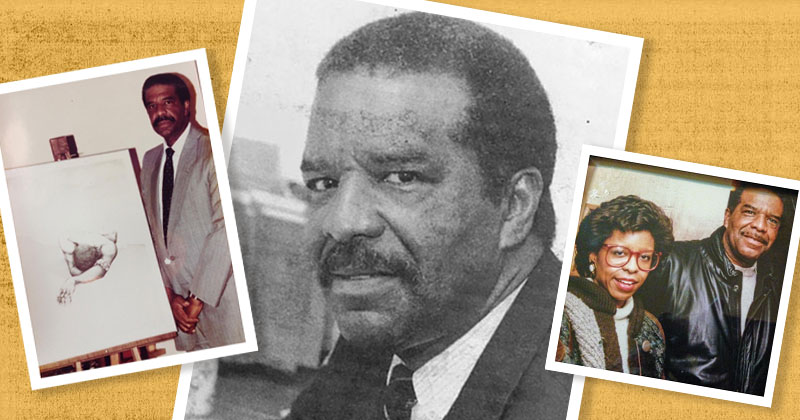

Brilliance and Resilience

The Legacy of Richard "Dickie" Wilson

October 07, 2020

When the phone rang in the wee hours of the night, my father always answered.

I could sometimes hear the front door shut and the car leave the driveway, knowing immediately that he was heading to campus to help someone

in need.

When a student could not travel home on a holiday break, they always sat at our dinner table and slept in our home. On hot summer weekends, our backyard and pool were filled with young adults who had large afros and wooden fists dangling from leather necklaces. Daddy called them his kids, even though my younger sister and I were his only biological children. But even as a young child, I was aware that he was a father figure to many.

I can’t remember a time when I didn’t share my dad with African American students at UD. I can’t remember a time when he wasn’t the go-to Black man on campus (after all, my parents made it clear he was one of the first, and for a great period of time, the only African American administrator at the University).

Richard Wilson’s UD career began in 1967, when he was named the director of Upward Bound, a ground-breaking federal program to introduce minority high school students to college life. While directing Upward Bound, he traveled up and down the state of Delaware, recruiting students and promising parents that their children would remain under his care. He carried large plastic garbage bags in his car, sympathetic to those concerned families who worried about sending their sons and daughters to a college campus filled with very few faces that looked like their own.

Still, my dad never took no for an answer and was instead determined not to let fear—or lack of a suitcase—prevent anyone from attending college. With a suitcase or garbage bag filled with their clothes, students across the state came to the University of Delaware, where they remained under my dad’s watchful eye. They would soon learn of his soaring expectation for them to excel academically, as if they were the standard-bearers for others to come.

My father also served in other roles at UD, as an admissions counselor and later, as the assistant to the vice president of student affairs. While in admissions, a co-worker recalled how he would see African American students lined up outside of my father’s office. When he offered to help them, they respectfully declined, as they’d been advised by their parents to only speak to Mr. Wilson.

Of course, those students weren’t the only ones wading in uncharted territory. Both of my parents realized the importance and gravity of my father’s influence. Before he was hired by the University, dad was a public school teacher. His breakthrough color-barrier move to UD meant trading in casual slacks and shirts for suits and ties. Every morning my mother would carefully lay out his new business attire, making certain everything was neatly pressed and in order. On some evenings they would attend social events hosted by other administrators. They openly talked about preparing themselves for a night when they would be the only brown faces present. My mother took great pleasure in dressing up and accompanying my father, even though her best girlfriends would be there, too; they also would be dressed up, but they were adorned with the black uniforms and white aprons of the wait staff.

Even before coming to the University, my dad had earned the reputation of being a caring but no-nonsense educator and disciplinarian.

As a college sophomore, New Castle County Councilman Jea Street, AS74, recalled feeling so disconnected and misunderstood that he told my dad he planned to quit and leave the University for good. According to Street, my father quietly closed his office door, then physically collared Street and shoved him to the floor telling him the only place he was going was to the library. After standing up and dusting himself off, that’s exactly where Street went—straight to the library.

Today those actions are unthinkable, even grounds for termination, but Street credits Dickie Wilson for those firm-but-caring measures that set him on a straight path. He attributes my dad’s tough love to his decision to become a lawmaker and director of the Hilltop Lutheran Neighborhood Center, where Street lovingly-but-sternly guided inner-city youth until he retired.

“Your dad looked out for the students categorized as the scholars, the athletes, the nerds and the gay kids at a time when being gay wasn’t acceptable,” he says now. And, much to his relief, Street said my father fought for the rights of young Black militants like himself and others, who in today’s terminology would be deemed “special populations.”

While each student was different in one way or another, they shared one thing in common: They were among the 125 African American students on a campus with more than 10,000 White students, faculty and administrators. My dad knew each one. “He took care of all of us and he understood that you couldn’t take children who were used to rules at home and all of a sudden put them in a place where there were no rules, so he would do things like pop in our dorms in the middle of the night, removing the liquor bottles that were sitting on our window sills,” Street says now, with a laugh. “I did the same to my children; that was a lesson that never went away from me.”

Along with demanding academic excellence, respect and discipline from his students, my father demanded that the University create a place where students of color would feel comfortable, safe and gain further guidance and support. With his help, the Center for Black Culture was created. And although my father personally feared that Greek-lettered fraternities and sororities would only divide the meager population of Black students, Street credits my dad with supporting their wishes to charter various Greek chapters.

Ironically, after my father’s untimely death at age 58 from pancreatic cancer, an annual “Dick Wilson Greek Step Show,” which initially had a scholarship fund attached, was estabished in his honor. Thousands attended from colleges and universities all over the East Coast. Despite his reservations about Greek life, I know he would have been proud to see so many young people of color coming together, not only for fellowship but for an opportunity to financially help other students enter college.

My father also embraced the arts, taking “his kids” to Broadway to see plays like Purley starring Melba Moore. He brought poets like Nikki Giovanni with her cutting-edge prose to campus, along with R&B singers like James Brown, who, at the time, had a hit record titled, “Say it Loud, I’m Black and I’m Proud.” My little sister and I tagged along on these excursions, too, getting first-time exposure just like the students. At Brown’s concert, I remember seeing an excited female fan faint. My father scooped her up as if she were a feather and carried her out and I vividly recall thinking then that my daddy was a big, strong superhero.

Dickie Wilson was a superhero in my eyes. He was strong physically, and even stronger in his convictions and the love for his students. That is why, even today, decades after his death in 1992, so many people tell me they credit their successful professional careers to my father. Strangers and friends tell me it was my father who single-handedly opened doors that were shut to them, fought for their rights and expected nothing short of excellence from each of them in return. Those people include Alton Williams, AS74, an optometrist; Alvin Turner, AS66, a psychologist; his brother Carl Turner, AS71, a physician; Ronald Whittington, AS71, former executive assistant to UD Presidents Arthur Trabant and David Roselle; Sylvester Johnson, BE75, former associate director of operations at the Bob Carpenter Center; the late Conway Hayman, AS71, a former NFL player; and many, many more.

Norma Gaines-Hanks, AS74, 97EdD, who is among the few of dad’s kids who still remain on campus as an associate professor and human services internship coordinator, keeps a photo of my father in her office to this day, saying it is a reminder of the shoulders on which she stands. “Suffice it to say that my journey at UD would have been very different if Richard Wilson had not been a major part of it,” she says.

I take great pride in knowing that the daddy I shared with UD’s Black students impacted so many of their lives, just as he impacted my own.

Sharing Richard “Dickie” Wilson made UD a better place and empowered his kids to make the world a better place. As the lone Black administrator on UD’s campus for many years, he embraced each student as if they were his own and inspired them to soar.

Contact Us

Have a UDaily story idea?

Contact us at ocm@udel.edu

Members of the press

Contact us at 302-831-NEWS or visit the Media Relations website