We're making a difference

41% of four-year college students nationally reported being “food insecure.” At UD, that number is cut by almost half.

April 23, 2020

From the outside, college can look so comfy: Stylish students stroll the manicured Green with studied coolness, their eyes glued to thousand-dollar cellphones, their bellies filled with diet-appropriate dining hall meals—their bills paid by mom and dad.

Now erase that image from your mind, and see the reality that more and more students face today: For them, college is a time of dilemma and distress, of wondering whether to buy groceries or pay rent, of toiling to make ends meet with outside work—yet still making the grade in class.

For these young adults, all it takes is one life crisis to bring their college career to a screeching stop. All it takes is a few unexpected bills to make nutritious food an elusive option.

And happily, all it takes is some Blue Hen compassion to ease their hunger.

As the promise of a degree attracts increasing numbers of “non-traditional students”—single parents, working adults and applicants from meager circumstances—UD is working to ensure their efforts aren’t undone by a lack of food. It’s a cause that has inspired action on the inside and outside of campus, generating eager alumni support, prompting acts of selfless student endeavor, and delivering a growing array of student resources, ranging from emergency funding to meal-ticket sharing programs.

“People tend to look at campus, and only see affluence,” says Prof. Kristin Wiens, coordinator of UD’s Food and Nutrition Education Lab. “The tough part with hunger is that it’s invisible. It’s a problem that doesn’t need to be in the dark. It needs to be in the light.”

Some unsettling facts

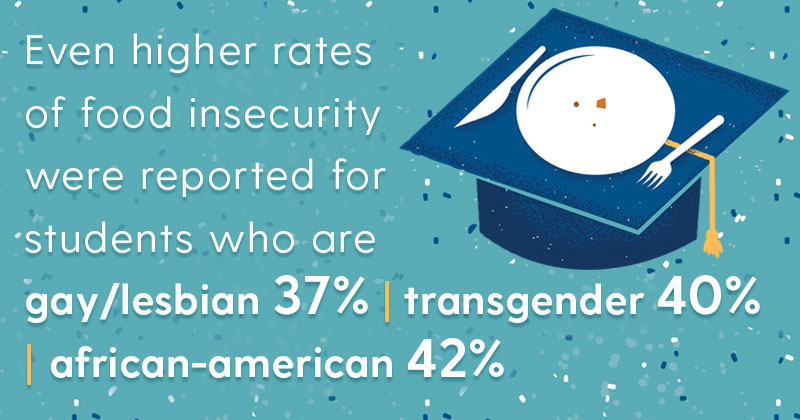

Student Katie Zimmerman saw that stark reality in her junior year when she first learned about the national problem of campus “food insecurity”—defined as a lack of reliable access to enough food for an active, healthy life. The facts disturbed her: A 2018 Temple University study found that 23% of UD students reported being “food insecure” in the last 30 days (the national average for four-year colleges is 41%). The problem is even greater for UD students who are gay/lesbian (37%), African-American (42%), or transgender (40%).

“Our rates of food insecurity are below the national average, but we’re not all that dissimilar from what other four-year institutions report,” Wiens says.

That was a compelling revelation.

“I was surprised by my own ignorance—that I didn’t even know about it,” says Zimmerman, AS20, who spent much of the past year and a half bringing a national program called “Swipe Out Hunger” to UD. The concept is simple: Students with unneeded “swipes” on their meal cards can donate them to a centralized pool, allowing the meals to be electronically dispersed to needy students’ own University cards.

Since the program’s launch last year, students have contributed 1,144 meals and $348 through a two-day dining hall donation drive, with more to come after this spring’s campaign is tallied. By the end of 2019, 10 students had sought out food assistance through the program, and there’s a strong sense that others just haven’t heard about it, or refrain from seeking help out of shame.

That stigma frequently undermines even the most committed outreach efforts, experts say. By electronically transferring meals to needy students, Swipe Out Hunger keeps their predicament out of public view. “You can still go to dinner with your friends through this program, which was super important for me,” says Zimmerman. “There’s still so much stigma people feel.”

Students are connected to the program through the Dean of Students Office, but many others at UD helped accommodate the effort, giving Zimmerman a valuable life lesson in being a behind-the-scenes catalyst.

“I’ve been incredibly lucky,” says Zimmerman, a neuroscience major who needed to become an impromptu expert in marketing, outreach and administrative politics. “There were pieces of it that as a student, I didn’t know how to deal with. But I didn’t have a huge amount of pushback.”

Blue Hens reach out

And neither did the people at the Dean’s Office when they embarked on a plan to reinvigorate UD’s 8-year-old “Student Crisis Fund,” which has traditionally been used to help students facing urgent mishaps, from apartment fires to slashed tires to busted laptops. “It’s meant for the student who doesn’t have that safety net, either through their family or through their network of friends,” says Meaghan Davidson, assistant dean of students.

After launching a focused fundraising campaign last year with the Alumni Relations Department, the Dean’s Office discovered that Blue Hen grads were eager to help strengthen the fund, giving $18,000—more than all the previous years combined. In 2019, the fund helped a record number of students—61% of them minorities, and 20% first-generation students.

Nationally, the need for such assistance is growing, even as the circumstances are becoming less tied to specific incidents, and increasingly related to broader difficulties in students’ lives. At UD and across the nation, the dynamics of college affordability seemed to be aligning in bleak ways: With tuition rates hitting all-time highs, the gap between financial aid and college costs is widening, creating a greater need for student loans or outside work—just as wages have begun to stagnate.

Other factors only intensify the predicament: Universities have been trying to accommodate more students from low-income families, but federal food assistance is available to college students only under rare circumstances, and even then it is frequently underutilized. Students can get a job to alleviate financial struggles, but experts say working more than 10 hours a week puts academic performance at risk—and working 10 or fewer hours doesn’t begin to cover today’s costs.

A study by the Education Trust found that many students have to work more than 40 hours a week to pay bills—essentially a full-time job—and Temple scholars say that the average UD student needs to clock 26.4 hours a week at a minimum-wage job to cover their tuition and living expenses. Relatively high rent in the Newark area exacerbates the problem, according to Wiens.

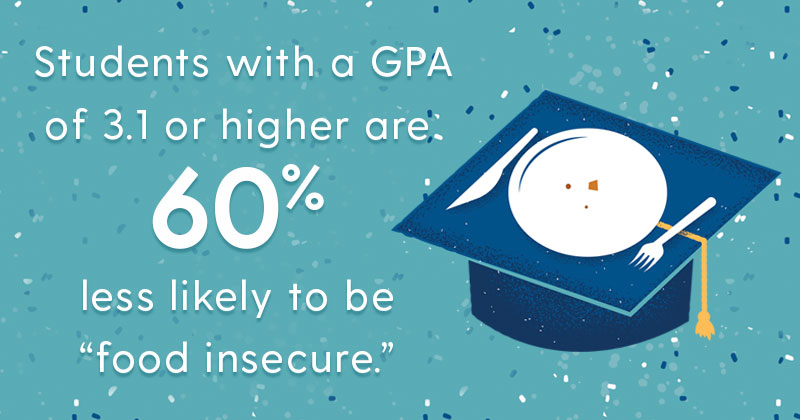

As they agonize over unpaid bills, hungry students are also at more risk of academic failure, studies have shown. A 2016 report in the Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior found a correlation between food insecurity and grades: Students with a GPA of 3.1 or higher were 60% less likely to be “food insecure.”

“We know what happens to a student off campus can be 100% connected to their college success,” adds Adam Cantley, UD’s dean of students.

Other research has found that hunger also triggers anxiety and depression, amplifying students’ pain and hopelessness. “The research suggests it impacts graduation rates and attention span,” says Weins, who has found that student veterans and graduate students are especially prone to food insecurity issues.

Yet despite the deeper awareness, the problem remains difficult to tackle, even as mounds of donated food grow. The Temple study found that stigma stands as a major barrier at many universities, making students reluctant to use resources such as UD’s Blue Hen Bounty food pantry (founded in 2016 by then-junior Carson Hanna, EHD18, at Newark’s St. Thomas Episcopal Church), and the Food Recovery Network (a student group that donates leftover dining hall food to pantries for use by both students and residents).

“They don’t get a lot of traffic through the door at Blue Hen Bounty,” says Weins, who is working to create a University-wide task force on campus hunger and homelessness. “The students who need the support are the hardest to get hold of. And they don’t see themselves as food insecure because it’s supposedly ‘normal’ to subsist on ramen and mac-and-cheese in college.”

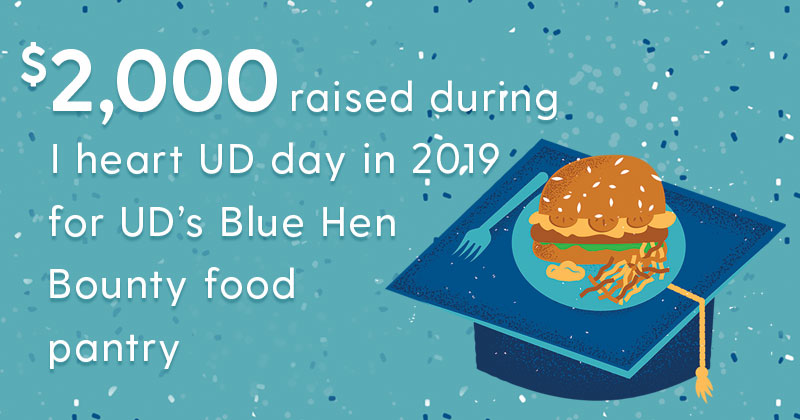

But the impulse to help remains strong at UD. Last year, nearly $2,000 was raised for Blue Hen Bounty through the philanthropic-focused I Heart UD Day, and the local Food Lion gave 6,200 meals. One father-and-son duo, Arin Nakirikanti and Kiran Nukiranti, coordinated a food drive during the Hindu festival of Diwali, ultimately donating 1,250 pounds of canned goods.

To the students who benefit, such generosity can be the difference between a degree and disaster. And there’s no doubt they sense that salvation, Davidson says.

“It almost makes me cry,” she says, “the emails we get, the gratitude they show.”

RESOURCES FOR HUNGER ON CAMPUS

- Students interested in volunteer or leadership opportunities with Swipe Out Hunger can contact Katie Zimmerman at katiezim@udel.edu.

- Students in need of food assistance can reach out to the Dean of Students Office at deanofstudents@udel.edu.

- Visit UD’s Blue Hen Bounty food pantry website

Contact Us

Have a UDaily story idea?

Contact us at ocm@udel.edu

Members of the press

Contact us at 302-831-NEWS or visit the Media Relations website