Conserving the curriculum

Photo by Evan Krape and courtesy of Annabelle Camp, Miriam-Helene Rudd, Joelle D. J. Wickens and Laura Mina October 13, 2020

UD’s art conservation team finds creative ways to teach during COVID-19

In the field of art conservation, much work involves assessing the condition of material objects — textiles, paintings, sculptures, photographs. This goes for artifacts that have been well preserved as well as those battered by a storm, literal or otherwise. When compiling a condition report, a conservator must come up with a treatment plan, a proposal for stabilizing said objects so they can survive long term.

Last spring, when the coronavirus (COVID-19) threw the country into upheaval, art conservation professors at the University of Delaware used their skills to formally assess the condition not of artifacts, but of their students. What is the treatment plan for graduates and undergraduates caught up in the coronavirus storm? Their education had thus far relied heavily on hands-on, laboratory learning, and now their classes would transition to an online format. Stabilizing objects is one thing but, in these conditions, how do you stabilize people for long-term survival in their chosen field?

For answers, UD’s experts looked no further than their own training as conservators. When it comes to preserving art, a stain or a crack or other imperfection is not necessarily a blemish to be scrubbed out or repaired. Instead, it can be an important part of the cultural heritage, a key to the story that ends up enriching the whole piece. Teaching during a pandemic? For some educators and their students, that is the crack in the vase or the smudge in the painting.

“This has been a really good growing, boundary-pushing exercise,” said Joelle D. J. Wickens, associate director of The Winterthur/University of Delaware Program in Art Conservation. “Sometimes, it takes something totally drastic to push you out of your comfort zone. You’ve been doing things the same way because that is what’s easy, and you just keep going. Then some big thing like a pandemic gets in the way, and you have to reevaluate. Often, I think, we come to a better place because of it.”

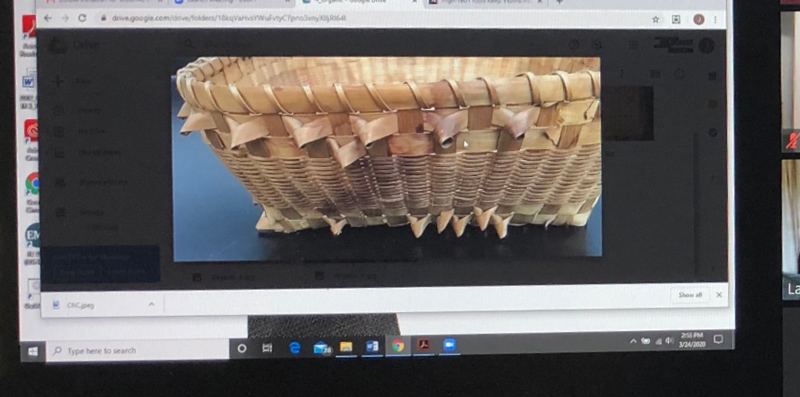

Take Nina Owczarek, assistant professor of art conservation. When the pandemic struck, her students were in the midst of documenting and treating the damage of objects — from Native American artifacts to Peruvian fly whisks — on loan from Bryn Mawr College. These items could not be taken off campus so, when the students were sent home, Owczarek improvised.

In a second-hand store in her hometown of Wilmington, she said she scoured for baskets — items that can be worked on outside a lab setting because the materials required for basketry conservation do not involve toxic chemicals. She then smushed these baskets, punctured holes in their sides and inflicted other damage for the students to cope with. Finally, she assembled take-home treatment kits that included paints, cosmetic sponges and other materials.

“Even though it wasn’t what we had necessarily hoped for, I definitely still learned a great deal about different hand skills,” said Miriam-Helene Rudd, an Honors senior assigned to one of the baskets. “I’m very grateful for how the art conservation faculty is adapting to ensure we still get the best experience possible. Everyone at UD has been so willing to help each other in navigating this period.”

For Laura Mina, associate conservator of textiles and head of the Textile Lab at UD who teaches students in the graduate program, the key has been remembering: While class delivery methods may change, the big picture does not.

“When I looked at my syllabus and thought: ‘How can I make this immersive textile class something my students can learn at home?’ that was really frustrating,” she said. “But when I went back to my list of priorities and the core competencies important for my students to learn, it was still challenging, but a lot less frustrating. I could say, ‘OK, maybe I need to find another way of working toward these goals, but I can still achieve them.’ ”

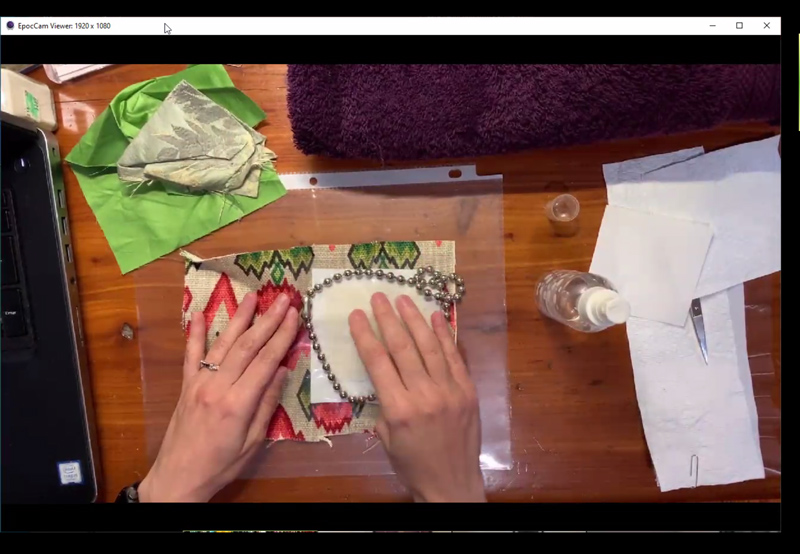

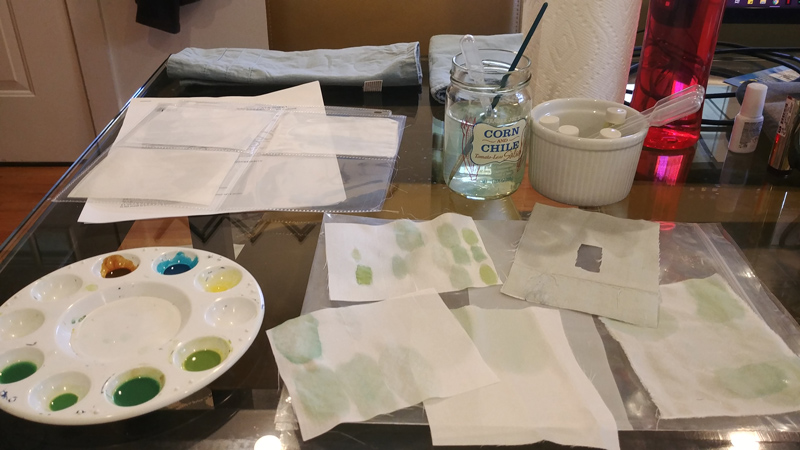

With the help of coworkers, paid interns and volunteers, Mina compiled nine take-home kits — four had materials for creating textiles off campus using methods like crochet, needle felting and a traditional Japanese embroidery technique known as Sashiko. Without access to the giant loom in the textile lab, Mina equipped her students with more portable devices that can be set up anywhere to enable tablet weaving on a body-tension loom. The rest of the kits had tools for completing various textile conservation techniques, like humidification and crease reduction. The students were given feedback and instruction over Zoom.

“In reality, very few conservators end up working in a pristine lab setting with access to deionized water and other resources,” said Annabelle Camp, one of Mina’s graduate students. “By figuring it out at home, we were able to see what it is like working as a private conservator out of a residence or historical site. In this situation, we learned the importance of being resourceful.”

Typically, these Blue Hens would also have completed an exercise related to the care of museum objects but, without access to a museum, they pivoted. Inspired by a hobby that continues gaining traction during quarantine — sorting through old stuff — the students undertook a public outreach project. For a series of blogs entitled “Attics and basements and closets, oh my,” they researched and shared their advice on caring for family heirlooms, from old photographs to quilts and jewelry.

“People often think art conservators are only treating museum objects, but we’re not,” Camp said. “We also train people on how to care for their own collections, because we truly believe that all objects, not just those deemed worthy of being in a museum, can speak to history. They can help us make invaluable connections across communities and across the globe.”

The real-world resonance of art conservation classes taught during the pandemic is a common refrain among professors reflecting on their COVID-19 classes. For one thing, the online format has allowed for classroom discussions that go beyond the technical side of the field — conversations, for instance, on the ethical issues that conservators will encounter once they enter the profession. One example, according to Owczarek, is a dialogue she facilitated about documentation — students are traditionally trained to value it as a cornerstone of the field. But what happens when, outside the classroom, they encounter an artifact from a culture that views photography as harmful?

“You build a coalition,” Owczarek said. “You start talking to people. You do research to find out if there is a safe way to document that is not harmful to the artifact or the people it comes from. It’s not as straightforward as you may think, and I am hoping my students come away with this sensitivity.”

Some pandemic-era pivots have been so successful, UD professors say they will hold on to them, even if and when the coronavirus is no longer an issue.

In one of Wicken’s classes, for example, she teaches emergency preparedness and response — in the event of a hurricane or flood, students learn best practices for rescuing submerged objects. In one exercise, the students are presented with large plastic tubs filled with water and artifacts, like paintings and ceramics, in need of saving.

“What I really want the students to do is assess the situation, to really figure out which objects are most at risk and which can probably sit in the water for a while without becoming more damaged than they already are,” Wickens said. But, in a traditional, in-person class, this is challenging. “As soon as a conservator sees something that is wet, there is this need and desire to get it out of the water right away. It is difficult to get them to take more than a minute or two to really talk things through.”

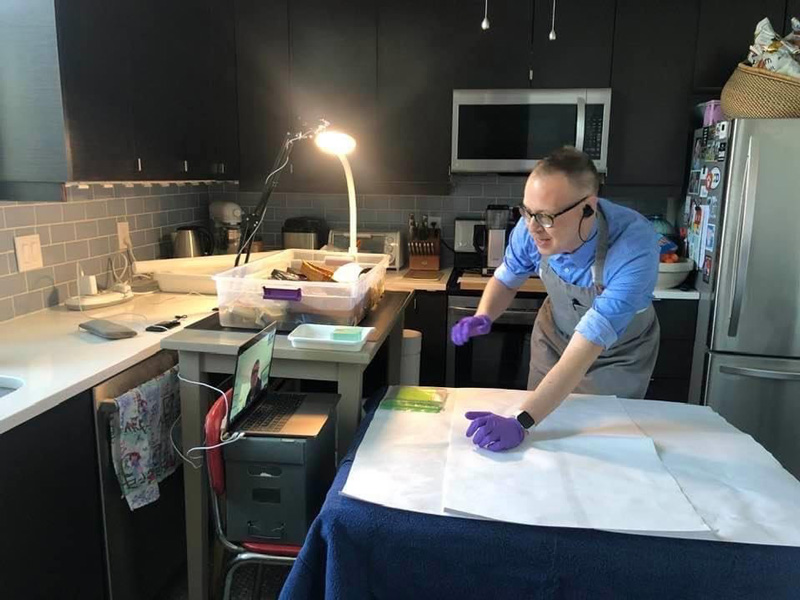

But during the pandemic, Wickens has conducted this exercise over Zoom. Her co-teacher, affiliated assistant professor William Donnelly, was in his kitchen with the tub of wet objects, while the students tuned in from their respective kitchens and bedrooms. Donnelly pretended to be someone without conservation expertise who needed help figuring out a plan of action. And the students, connecting in this virtual manner, took the time to flesh out this plan before having Donnelly dive in.

“They had no choice but to talk to one another,” Wickens said. “I’m pretty sure even when we’re back on site, I’m going to continue doing the exercise in this way.”

This isn’t to say the restrictions of COVID-19 have been easy. The professors attest long Zoom sessions can feel more formal and disconnected than in-person instruction, which is why they choose to humanize their courses by building in time for discussions that have nothing to do with curriculum — about, say, household pets who wander across the screen.

“We take our work very seriously, but it’s nice to allow for those moments of joy or lightheartedness in the day,” said Mina, the owner of a particularly fluffy cat who is part Maine Coon. “It helps you feel more connected to one another, even when we can’t physically be together.”

And when things feel too tough even for a cute kitten or puppy to rectify? The professors and students say their Blue Hen values of resilience and adaptability see them through. As does dedication to the mission that remains at the heart of all conservation work — even, or perhaps especially, during a pandemic.

“Artifacts bring us together,” Owczarek said. “They show us who we are as people. They help us feel connected to our history and our present, and they can shape the direction we go in our future. Taking care of them inspires us to be our best selves.”

Contact Us

Have a UDaily story idea?

Contact us at ocm@udel.edu

Members of the press

Contact us at mediarelations@udel.edu or visit the Media Relations website