Before and after seafloor eruption: https://capture.udel.edu/media/1_vann56hx/

Seafloor eruption

Photos courtesy of Andrew Wozniak, University of Delaware; HOV Alvin Team; Funder: NSF. © Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution | Video courtesy of Andrew Wozniak, University of Delaware; HOV Alvin Team; Funder: NSF. © Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution May 09, 2025

UD scientists witness rare volcanic eruption along the East Pacific Rise

Led by the University of Delaware’s Andrew Wozniak, associate professor in the School of Marine Science and Policy, a team of scientists recently witnessed a rare seafloor eruption 1,300 miles west of Costa Rica, along the East Pacific Rise. The eruption has been anticipated for more than seven years and sets the stage for deep-sea scientists to document the effects of an eruption on hydrothermal vent systems and on life in the deep ocean that has evolved in a dynamic and often harsh environment.

“It doesn't feel real at the moment, but to be able to observe what we saw and be able to collect samples is really mind-boggling,” Wozniak said. “I'm so excited for my team, and I'm really excited to see what we can learn about what's happening down there.”

The expedition aboard the research vessel Atlantis includes a group of scientists and students from the University of Delaware, Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute (RPI) and Middle East Technical University. They arrived on site on April 11 and began a series of dives in the research submersible Alvin, which is owned by the U.S. Navy and operated by the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) for the entire oceanographic community as part of the NSF-funded and Office of Naval Research-supported National Deep Submergence Facility. The goal of the expedition was to study the influence of hydrothermal vents on the movement of dissolved organic carbon through the deep ocean.

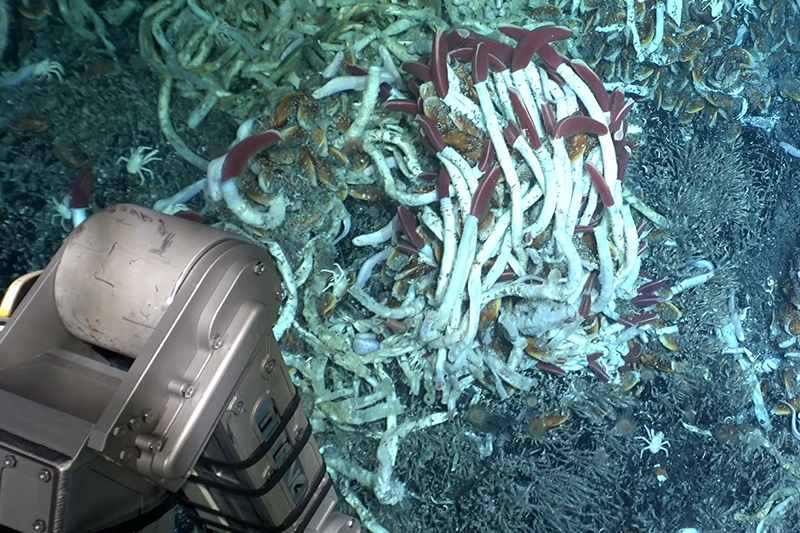

Three people — two scientists and a pilot — customarily dive for eight to 10 hours per day to a maximum depth of 6,500 meters (4 miles). On April 28, scientists diving in Alvin to the site known as the Tica hydrothermal vent about 2500 meters below the surface witnessed what dozens have seen before: a vibrant ecosystem of tubeworms, mussels, crabs, fish, and many other animals clustered around towering hydrothermal vents that billow hot (more than 750°F), chemical-laden fluids rich in hydrogen sulfide from deep beneath the seafloor.

The next day, Wozniak and Alyssa Wentzel, a UD undergraduate honors student double majoring in marine science and public policy, encountered a very different scene.

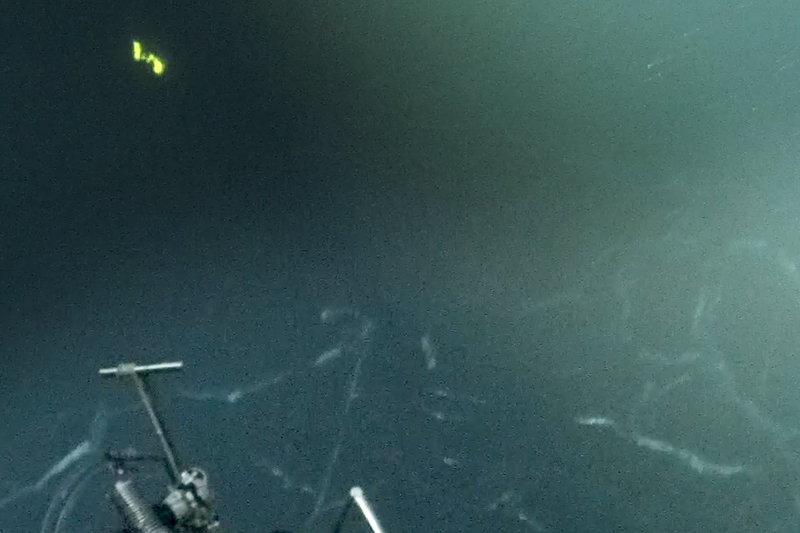

On their approach to the bottom, the team in Alvin noticed additional particulate matter in the water and slightly elevated temperatures. It wasn’t until their lights illuminated the seafloor, however, that what they saw surprised them.

“Tica was barren,” Wozniak said. “Almost completely gone.”

Through the hazy water, the group inside the sub could see fresh basalt — hardened lava — covering dead stands of tubeworms. They also saw flashes of molten lava appearing briefly before the near-freezing seawater caused it to harden.

As a result of what they observed, and in keeping with standard safety guidelines, Alvin pilot Kaitlyn Beardshear ended the dive and brought the submersible back to the surface for a normal recovery.

“We have temperature limits to ensure the safety of the sub and its occupants,” Beardshear said. “When we saw an orange shimmering glow in some of the cracks, it confirmed that a volcanic eruption had taken place and was still actually underway. I kept a close eye on the temperature as we were traveling, and it kept climbing higher until I decided it was a good idea to leave before we reached the limit.”

Although remaining dives in Alvin were cancelled due to the uncertain conditions on the seafloor, scientists on board Atlantis lowered instruments to gather as much data as they could before the end of the expedition on May 3.

“We were able to very carefully maneuver our sensors and sampling bottles to within meters of the space that had been occupied by the Tica vent structure and its biological community just a day earlier,” said Sunita Shah Walter, assistant professor in UD’s School of Marine Science and Policy.

“This is the first time that we will have chemical analyses of water samples during an eruption and will be invaluable in documenting the eruption process and how it affects the chemistry of the bottom waters as these are dispersed away from the vent field to the ocean,” said UD’s George Luther, professor emeritus.

Tica and nearby hydrothermal vents have been the focus of intense research since their discovery in 1991, when a previous volcanic eruption was witnessed, again by scientists diving in Alvin. The site has experienced three volcanic eruptions since then, spaced approximately 15 to 20 years apart, but the effects have only been documented after the fact, sometimes months later. Each time, the vent-based ecosystems have rebounded, beginning with the appearance of delicate mats of bacteria capable of converting the chemicals in hydrothermal fluid into organic matter that becomes food for larger animals.

Changes in the chemical composition of the hydrothermal fluids at the site, as well as steadily rising temperatures measured by specialized instruments installed in the vents and recording data every 10 minutes, indicated to scientists that an eruption was imminent. Previous visits over the past 7 years to this East Pacific Rise study site by another group of scientists, also funded by NSF, had predicted the eruption.

“Monday, everything was normal, Tuesday it was paved over, so we know the timing of the eruption to within hours,” said WHOI marine geologist Dan Fornari, who has studied Tica and nearby vents since 1991, but who was not on the current expedition. “This will give us a better sense of what the precursors are to an eruption.”

As the scientific community begins to take stock of information coming back to shore, attention has turned to planned and potential future visits to the same site. High-resolution maps of the study site made over the past seven years using an autonomous underwater vehicle (AUV) Sentry, also operated by WHOI, will allow geologists to determine exactly where the eruption occurred, how much of the seafloor was covered by fresh flows, and the volume of lava erupted. Chemists will be eager to learn how the composition of hydrothermal fluids changed pre- and post-eruption. And biologists will again begin to document how the ecosystem changes in the coming years as the site is recolonized.

“With any volcanically active region, you have a cycle of death and rebirth,” said Sasha Wagner, assistant professor of earth and environmental sciences at RPI, who visited Tica several times in the weeks leading up to the eruption. “Today, we witnessed the end of the living, vibrant part of this community. It was destructive, but at the same time, it's an opportunity for revival.”

This project is funded by the National Science Foundation (OCE-2148471, University of Delaware; and OCE-2147634, Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute).

Contact Us

Have a UDaily story idea?

Contact us at ocm@udel.edu

Members of the press

Contact us at mediarelations@udel.edu or visit the Media Relations website