NSF CAREER Award

Photo by Evan Krape December 10, 2025

Microbiologist Molly Sutherland studies essential protein with National Science Foundation funding

Each day, the University of Delaware buses transport students around campus. The Academy Street line, for example, ferries students to stops including the Tower at STAR, Perkins Student Center and Wolf Hall.

Cytochrome c is a protein found in the body’s mitochondria (the powerhouse of animal and human cells) that performs a similar function, acting as a shuttle carrying electrons to help cells create energy. It also is involved in turning on the body’s system for destroying and removing damaged cells, a process known as apoptosis. There are many members of the cytochrome c protein family, which play key roles in essential cellular processes in humans through bacteria, such as respiration, photosynthesis and detoxification. Cytochromes c are found in plants and bacteria, too, but how they are made isn’t well understood.

Armed with a five-year, $1.38 million National Science Foundation Early Career Development Award, Molly Sutherland, assistant professor of biological sciences, plans to improve what is known about how cytochromes c are made in bacteria.

There are many cytochromes c, all of which are made by one of three pathways, two found in bacteria and one in mitochondria. Sutherland’s research focuses on bacterial pathways.

It’s an important line of study when you consider that cytochromes c are required for bacteria to make energy, a process called bacterial bioenergetics.

Figuring out these details has the potential to advance understanding of different ecosystems. It has implications for agriculture, for example, where bacteria work with plants to perform a critical part of the nitrogen cycle that converts nitrogen gas into forms plants can use or to decompose organic matter. There also are implications for human health, including the development of antimicrobials.

For instance, the human gut microbiome helps break down nutrients that the body can't digest naturally. If Sutherland can figure out what sort of energy sources might turn one of the cytochrome c biogenesis pathways on or off, that knowledge could inform what’s known about certain health conditions like Crohn's disease, which has an inflammatory factor that has to do with the gut. There are other applications, too.

“If we can understand how bacteria can grow, then we can understand how to prevent them from growing,” said Sutherland. “In terms of applied chemical engineering … oftentimes to have bacteria make a compound we want, we need to control and direct their metabolism in a certain way. If we can understand how to make these cytochromes c, we can use that information to impact things like the design of antimicrobials or the production of a certain chemical we want to move into bacteria because it's more efficient or more environmentally friendly.”

So, how does Sutherland go about her work?

“As a geneticist, the way you normally figure something out is, essentially, you try and break it to figure out what parts are important,” said Sutherland. “We can't do that in many bacteria, because they will die without these pathways. If they can’t make energy, they can’t grow.”

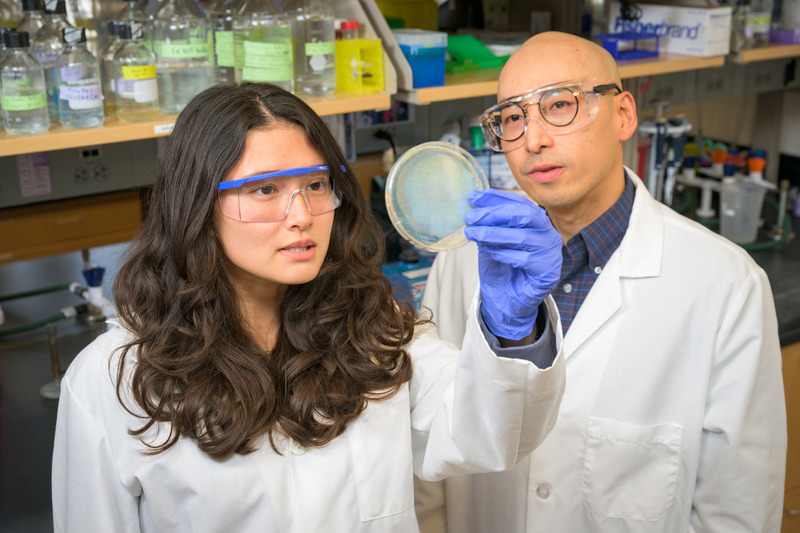

Experimentally, Sutherland and her research team take these proteins from other bacteria and put them into Escherichia coli (E. coli). E. coli is considered a model system for this type of experimentation because it doesn’t require cytochromes c to make energy in the presence of oxygen.

“We grow up a lot of E. coli, we purify the proteins out and then we see what our mutations have done to them,” said Sutherland. “If we can get to the point where we can biochemically understand the similarities and differences between these pathways, that will open up a lot of exciting avenues to set up collaborations to move toward understanding how it works in the gut microbiome, for example.”

Here, Sutherland’s work will focus on the fundamental pathways that make cytochromes c in the bacteria Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron (B. theta). Unlike most bacteria that encode a single cytochrome c biogenesis pathway, B. theta has four distinct pathways for the bacteria to make cytochrome c in the same organism.

According to Sutherland, this is unusual.

“It doesn't make sense. Bacteria don't just keep genes around, they keep things that are useful,” she said. “And in this case, we know that each of the pathways has a cytochrome c encoded in the genome near it. So, we're thinking that there's something specific that has evolved.”

Understanding why there are four pathways instead of one could also provide researchers information on how cytochrome c biogenesis is regulated, leading to better understanding of how the bacteria makes energy.

To tease this apart, Sutherland and her team will use bioinformatics to explore whether other bacteria encode multiple copies of cytochrome c biogenesis pathways and to look at the evolution of these pathways, which are still unknown 30 years after their discovery.

Roadmap to research experiences

As part of the award, Sutherland is developing guided exercises to aid students in connecting to undergraduate research opportunities, in collaboration with UD’s Academic Information Technology (IT) unit. She plans to use the tools with her students and to share the materials with other professors teaching introductory microbiology or biology courses that reach students with a variety of majors.

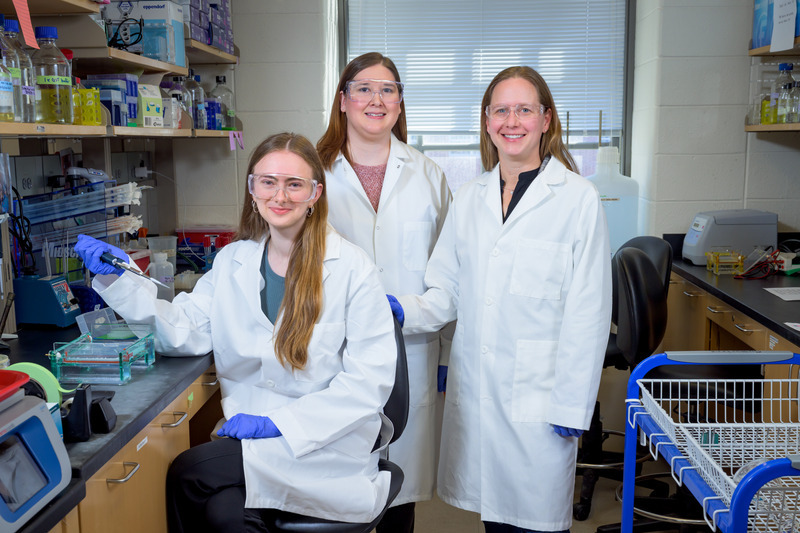

Sutherland also supports undergraduate student researchers in her lab, pairing them with more seasoned graduate students to build an informal mentoring network in her lab. While undergraduate students are trained on how to do research, the graduate students — our future scientists and leaders — are building their skills in effectively mentoring other scientists.

Last summer, for example, undergraduate researcher Eveyln McQuaid was supervised by graduate student Raymond Tsao.

“Having students in the lab gives them concrete skills that they can apply in graduate school or in entry level positions. I think my teaching is going to be more impactful to society because it's growing new scientists,” said Sutherland, who just last year had her first UD undergraduate student co-author a journal paper.

Contact Us

Have a UDaily story idea?

Contact us at ocm@udel.edu

Members of the press

Contact us at mediarelations@udel.edu or visit the Media Relations website