Illuminating the Anglo-Saxons

Photos by courtesy of the British Library December 10, 2018

UD’s Nees to give keynote lecture at major British Library exhibition

Lawrence Nees has been teaching University of Delaware students for 40 years, and lecturing around the world about art history for even longer than that, but he’s about to deliver what he calls “probably the most significant lecture of my career.”

The H. Fletcher Brown Chair of Humanities and professor and chair of art history at UD will be the opening keynote speaker on Thursday, Dec. 13, at an international conference at the British Library in London.

The conference, attended by senior scholars of medieval art and English literature, is being held in conjunction with the library’s blockbuster exhibition, “Anglo-Saxon Kingdoms: Art, Word, War.”

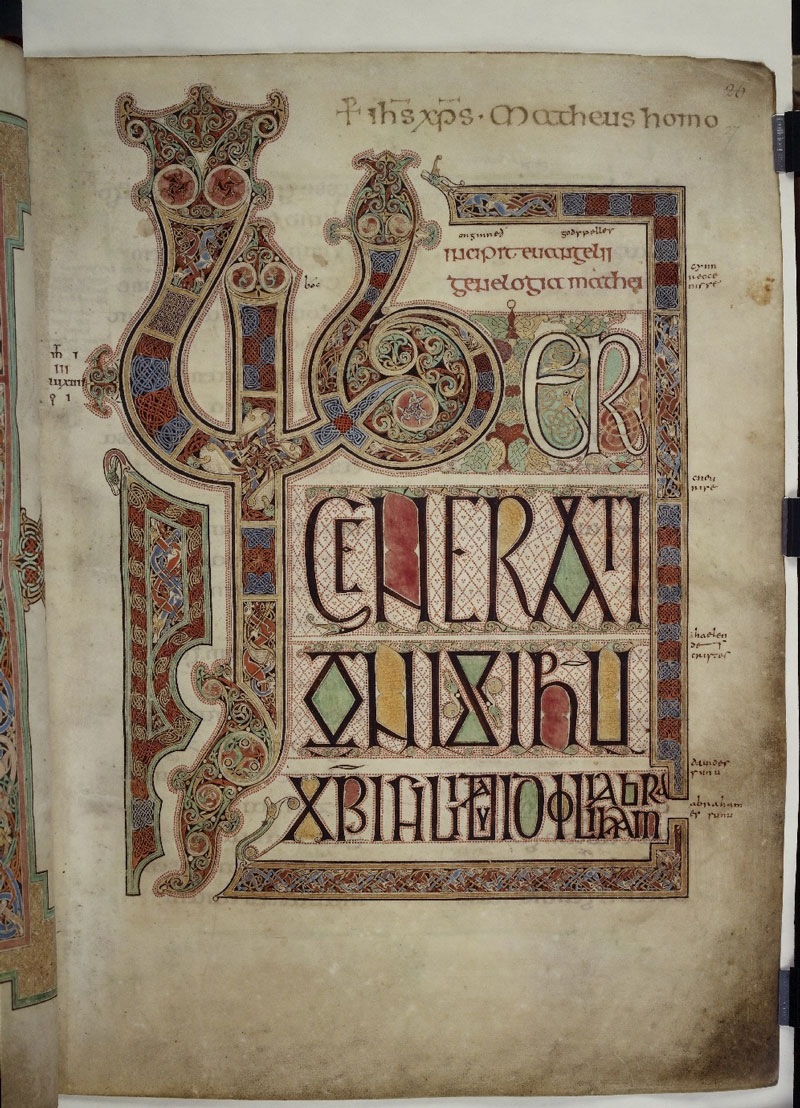

The exhibition, which has been called a once-in-a-generation opportunity to view treasures from numerous collections, showcases some of the earliest surviving words ever written in English and many lavishly decorated hand-written books from the 5th to 11th centuries. Works such as an original Beowulf manuscript and the earliest complete Latin Bible — which was returned to Britain from Italy for the first time in 1,300 years in order to be part of the exhibit — are on display, telling the history of the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms and the period’s literature, art and culture.

Nees is a noted scholar of early medieval art, but as an American, he said he was taken by surprise when he was contacted two years ago and invited to deliver the keynote lecture at the conference on manuscripts in the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms.

“I was shocked,” he said. “Thrilled, of course, but shocked that they asked me.”

His lecture is titled “The European Context of Manuscript Illumination in the Anglo-Saxon Kingdoms, 600-900,” and Nees said the word “European” is key.

While the term “Anglo-Saxon” may have popular connotations, especially in America, of ethnic privilege and elitism, Nees said the British Library was particularly interested in emphasizing the cross-cultural aspects of the period covered by the exhibition. That perspective fit perfectly with Nees’ own scholarship and teaching, which explores the way art and ideas traveled throughout continental Europe and Britain in the Middle Ages.

“Ethnicity in the medieval period is a big issue of study,” Nees said. “Scholars are increasingly interested in understanding the migration that occurred and the way various cultures contributed to art and to knowledge in general.”

For example, he said, books that were created by monks in seemingly isolated British monasteries were distributed to monasteries throughout continental Europe, just as European monks took part in the same kind of distribution in reverse. Irish artists studied in Rome, brought new techniques back home with them and remained in contact with their Italian teachers.

Even new ways of writing — the introduction of punctuation and of using spaces to separate words occurred during this period in Old English — were once thought to have been invented by the Irish or Germans, but actually appeared in many cultures around the same time, Nees said.

“There was a lot of cross-cultural movement in the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms,” he said. “It’s almost impossible to look at a painting and tell if an Irish or Italian or French artist painted it.”

With such contemporary issues as migration and Brexit, the move for the United Kingdom to leave the European Union, in the news in recent years, those planning the British Library exhibition wanted to make sure to include a wider European perspective.

“The cultures of the U.K. and the European continent are very entangled, with links and networks developing constantly,” Nees said. “A major part of my scholarship and my teaching concerns this.”

The University of Delaware’s Department of Art History is known for a focus on American art, but faculty members work in many geographic areas and have established numerous professional connections with institutions, scholars and students internationally, Nees said.

Indeed, it was a lecture he gave about race and ethnicity a couple of years ago at the Courtauld Institute of Art in London, attended by a British Library curator, that led to his current lecture invitation at the library.

“Our faculty have many personal contacts, but our program itself is quite well-known also,” Nees said. “When European institutions are looking for a partner to study American art, they come to UD.

“Of course, at this [British Library] conference, there will also be people who won’t have heard of UD, so it’s a good opportunity for them to learn about us.”

Contact Us

Have a UDaily story idea?

Contact us at ocm@udel.edu

Members of the press

Contact us at mediarelations@udel.edu or visit the Media Relations website