Biotechnology solutions for plastics problems

Photos by Evan Krape November 03, 2025

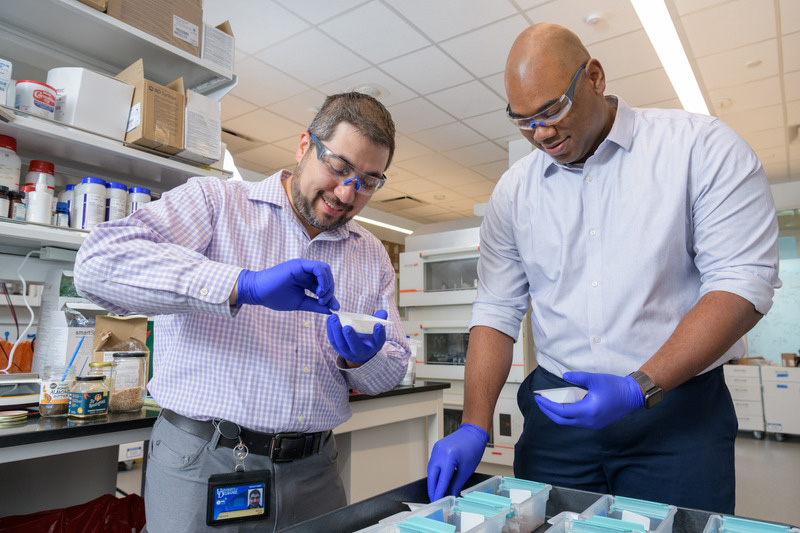

UD chemical engineer wins the AIChE Langer Prize for efforts to harness biology to manage plastic waste sustainably

Of the nearly 400 million tons of plastic waste produced annually, about half ends up discarded, polluting landscapes and waterways worldwide. Developing sustainable ways to recover, break down and transform plastic waste into useful materials remains challenging.

The University of Delaware’s Mark Blenner is addressing this challenge by harnessing biotechnology to degrade polyethylene, a hard-to-recycle plastic commonly found in single-use films and packaging. His efforts have earned him the 2025 Langer Prize for Innovation and Entrepreneurial Excellence from the American Institute of Chemical Engineers (AIChE).

Blenner, one of the Thomas and Kipp Gutshall Career Development Associate Professors in UD’s Department of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering (CBE), earned his doctorate from Columbia University and completed postdoctoral work at Harvard Medical School.

He will receive the Langer Prize and present an associated lecture on November 3 at the 2025 AIChE Annual Meeting in Boston. The prestigious honor, named for biomedical pioneer Robert Langer of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, awards an unrestricted grant of up to $100,000.

“Mark’s work exemplifies the creativity and collaboration needed to drive solutions to society’s most pressing environmental challenges,” said Pamela M. Norris, dean of the College of Engineering. “The Langer Prize recognizes his innovative approach and the potential of his research to drive transformative impact.”

From podcast to partnership

While the Langer Prize is an individual honor, Blenner emphasized that the effort reflects a close partnership with Kevin Solomon, also a Thomas and Kipp Gutshall Career Development Associate Professor in CBE. They launched the project shortly after both joined the UD faculty in 2021.

The inspiration, Blenner said, came from a podcast episode about insect larvae that can break down plastics. Evidence at the time suggested that microbes in the larvae’s gut were responsible, much like how animals require microbes to digest complex carbohydrates.

The Blenner lab focuses on engineering biology to solve problems in sustainability, human health, national defense and space exploration. Solomon, an expert in microbial approaches to breaking down and repurposing complex materials, brought complementary expertise. Recognizing a need for expertise in polymer characterization, they brought Distinguished Professor of Engineering LaShanda Korley and her group into the project. The research team also has a growing network of external collaborators.

“This project reflects the collaborative, innovative spirit we value in the department,” said Millicent Sullivan, the Alvin B. and Julie O. Stiles Professor and Chair of CBE. “It’s exciting to see ideas from our labs advance solutions to one of today’s most pressing environmental challenges.”

How biology modifies plastic

The team studies the yellow mealworm, the inch-long larval stage of the mealworm beetle, to understand how biology can break down plastic. Their research has confirmed that microbes in the worm’s gut are responsible for degrading polyethylene, one of the most common and stubborn plastics.

“Winning the Langer Prize is an important recognition of the hard work we’ve been putting into the difficult problem of plastic waste, particularly polyethylene. It validates that our work is rigorous, important and impactful,” said Blenner.

So far, the researchers have identified the first step in polyethylene breakdown. Microbial enzymes called dye-decolorizing peroxidases (DyPs) add oxygen, weakening bonds within the polymer and making it more susceptible to further degradation by other, yet-to-be-identified enzymes. The researchers are now investigating those next steps.

As they explored the mealworm’s microbiome, they also discovered fungi that interact with microplastics, tiny fragments of plastic that accumulate in the environment. These fungi produce proteins that cause microplastics to clump together, a process that could help remove them from water supplies. Blenner also sees potential in combining these fungal proteins with plastic-degrading enzymes to enhance plastic recovery and breakdown.

From discovery to real-world impact

Blenner’s team participated in National Science Foundation I-Corps training to explore how their research discoveries could meet industry needs. With the Langer Prize funding, Blenner plans to launch a company, study the market and identify near-term applications for enzyme technology to break down and repurpose plastic waste. “The goal is to find the right problem to tackle first, rather than immediately attempting a full recycling solution,” he said.

In the lab, the team is re-engineering DyPs to improve their activity, stability and lifetimes and make them more suitable for large-scale applications.

They also are exploring how these enzymes could add value by modifying plastics for reuse or transforming them into new materials. Because polyethylene cannot easily be converted back into its original building block, ethylene, the researchers are focusing on the intermediate compounds produced during degradation. The goal is to upcycle those intermediates into higher-value products.

Developing new technologies also means developing new talent. Training the next generation of researchers is a key part of Blenner’s mission. Twelve undergraduates have contributed to this work so far, of whom three have co-authored published journal articles and six have gone on to graduate programs. “Undergraduate research gives students the ability to not only apply the knowledge they gain in classes but also allows them to create new knowledge that drives innovation and prepares them to tackle sustainability challenges in their own careers,” said Blenner.

As global plastic pollution continues to mount, Blenner sees biology as a powerful tool for change. Backed by the Langer Prize, he and his collaborators are turning biotechnology innovations into tangible solutions for the world’s growing plastics challenge.

Contact Us

Have a UDaily story idea?

Contact us at ocm@udel.edu

Members of the press

Contact us at mediarelations@udel.edu or visit the Media Relations website