Out of the ashes

Photos courtesy of Margalit Schindler, Alejandro Cordero, Andrés Vázquez and Kiernan Graves June 12, 2025

UD art conservation alumni offer help to those affected by L.A. fires

They’re not first responders or civil engineers. They’re not trained counselors or shelter operators.

But when a series of deadly fires ravaged southern California communities in January, killing 30 people, displacing more than 200,000 and destroying thousands of structures, University of Delaware alumni Madison Brockman and Margalit Schindler found an important way to help their neighbors address some of the extraordinary challenges left behind.

Brockman and Schindler are highly skilled art conservators, graduates of the prestigious Winterthur/University of Delaware Program in Art Conservation. Now in private practice in the Los Angeles area, both are part of an emerging volunteer group — Art Recovery Los Angeles (ARLA) — that was born after the fires to help residents salvage, evaluate, stabilize and find appropriate treatment for prized objects, papers and textiles that survived the smoke and/or flames.

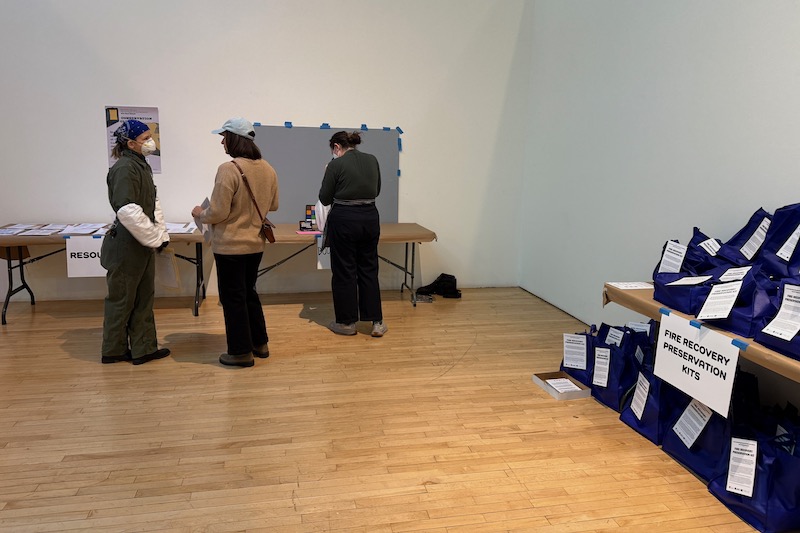

The demand for such help is high, as they discovered when ARLA held its first public clinic in March. In partnership with the Los Angeles County Department of Arts and Culture and the Armory Center for the Arts, about 50 volunteer conservators and about 120 community members participated in that first four-hour event, Schindler said. A second was held in April at The Geffen Contemporary at MOCA (Museum of Contemporary Art) and a third is planned for June 14 at The Getty Center.

The clinics are free to the public, Schindler said, with volunteer conservators donating what would have amounted to more than $50,000 in billable conservation time so far. As they build this new partnership, members recognize that their help will be needed in future disasters, too.

“We were overwhelmed,” said Schindler, who graduated from the WUDPAC program in 2022 with a concentration in preventive conservation and now chairs ARLA’s nascent board of directors. “I didn’t sit down all day. The need is beyond anything we’ll ever be able to meet.

“But it was amazing and delightful. I was expecting it to be much more somber, with an air of trauma — and there were those moments. There were people who had lost their homes that were overwhelmed. But the air of the day was overwhelmingly positive, with gratitude in all directions.”

Everyone who came got a consultation with a conservator who specialized in the material of the object they brought. Community members heard about potential options for treatment, what sort of supplies could be helpful, what the next steps could be.

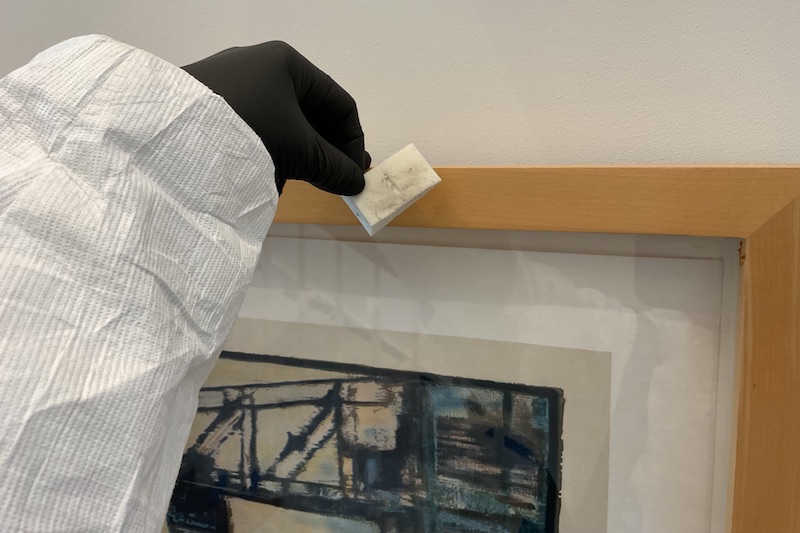

These consultations required careful consideration of personal safety. So much toxic material was left behind by the fires — in the air, on objects, in the ground and in the waterways — that handling and working with items exposed to these hazards could be dangerous indeed.

Personal protective equipment (PPE) — masks, Tyvek aprons and sleeves, gloves — was mandatory for the conservators, who were also urged to bring special vacuums that could be used to clean objects without damaging them.

“It was a BYOV event — bring your own vacuum,” Schindler said. “We used HEPA filter vacuums. If the object was safe and stable enough, the conservators would do the vacuuming for you and send you home with a cleaner piece while demonstrating how to use the vacuums and sponges — and now you can do the work.”

Do-it-yourself cleaning kits, including PPE, were provided free of charge by the Los Angeles Department of Art and Culture, too.

For such a time as this

Students never really know where their studies will take them, what their training might prepare them to do.

But in this case, these two WUDPAC graduates knew they were ready and willing to invest their expertise to address the needs of their community.

“Our graduate students are well-prepared with knowledge, skills, critical thinking, communication skills and leadership skills to help in these situations,” said Debra Hess Norris, director of WUDPAC, Unidel Henry Francis DuPont Chair and professor of photograph conservation at UD. “And to be there — it’s not just the hands-on work. It’s also the emotional work. They have the skills and knowledge and capacity to help, and they also have the need and obligation to help. And they do so brilliantly. I’m so grateful they’re able to get involved and we continue to incorporate this kind of education and training in our core curriculum.”

Brockman’s art conservation journey started briefly with objects, before moving into paper conservation during pre-graduate program internships.

“There’s so much paper in the world,” she said. “It’s a very widespread democratic-type medium. Everybody has paper — whether it’s a fine art project, ancient papyrus, an old master print or drawing, a movie star’s signature that you got on a cocktail napkin or family archives.”

Paper conservation is deceptively difficult, Brockman said.

“We do either dry treatment or wet treatment — water-based treatments. There’s no real room for error,” she said. “It can be super, super delicate. I like the challenge that comes along with that.”

Brockman grew up in the Los Angeles area and returned there after graduating from the WUDPAC program in 2019.

After moving back to Los Angeles, Brockman worked at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. She now works in private practice with L.A. Art Conservation, a firm specializing in paper conservation started by former LACMA colleague Erin Jue.

Schindler, who graduated from the WUDPAC program in 2022, said UD was supportive of a critical goal to work with items related to Judaica and Jewish culture.

“Part of my first year of grad school was figuring out what that meant,” Schindler said. “What does the community need? What should I study in order to best support them? I landed on a newer field — preventive conservation. UD was the only grad program that offers that major.”

Schindler was the fourth to graduate with that degree.

“I describe it as being a primary care physician as opposed to being a heart surgeon,” Schindler said. “We look at things in a zoomed out way. We look at the wellness of the collection, wellness care, capital ‘S’ Sustainable and little ‘s’ sustainable. We want to make smart choices that have a smaller carbon footprint, and we want to give a realistic path forward, within the available resources.

“I carved out a Jewish/Judaica subfield and it has been such a blessing. I knew I wanted to support small collections that would never be able to support a conservator full time.”

Now, as a “solopreneur” and founder of Pearl Preservation, Judaica and Jewish material culture is the focus. There is secular work, too, but the Jewish work carries special weight.

Schindler moved to L.A. from Wilmington, Delaware, about a year ago, found a robust conservation community and some great neighbors.

Suddenly, in January, everything changed as some of the most destructive wildfires in California history swept through their region on a 24-day rampage.

Living through the trauma

Neither Brockman nor Schindler lost their homes in those fires. But evacuation orders soon came for Schindler’s Runyon Canyon community.

They had 10 minutes to pack up. Pro tip: Decide before an emergency which three nostalgic items you’re going to take with you. Schindler and a neighbor had recently had exactly that conversation.

“The blanket my grandmother knitted for me — that was priority No. 1,” Schindler said. Then there were journals full of art and doodles and drawings and collages, along with a small container of “tchotchkes” — those little household trinkets that often become heirlooms.

Then came a flood of other questions.

“Where are we going to go? What do we do? We couldn’t hear each other over the sirens and the flames were four blocks away. I hopped in my neighbor’s car and we drove to her parents’ house and crashed there a few days.”

That L.A. community vibe was powerful, Schindler said.

“It was ‘Come share my childhood bed at my parents’ house and we’ll figure it out together. Jump in our car if you need to.’ People were checking in left and right. It’s an Angeleno ‘we are in it together’ attitude.”

It was a jarring stretch of time — an experience that provided special empathy for those who had so many questions about objects they had saved or salvaged.

“In some ways, it helps. I can understand what people are going through because I went through it. Those 10 minutes — that rush of adrenaline was crazy and it was really scary. I can connect with people in that human way.”

Stress and anxiety were common throughout the region.

“We have dealt with wildfires before and crazy El Ninos,” Brockman said. “But this was the biggest and closest incident. I’ve lived here my whole life and this is the worst I’ve ever experienced. The weather patterns over the last 30 years are very different now than when I was a kid.”

One way forward was to help. It was a much different kind of help than typical conservation work.

“Ordinarily, it’s people who just want to conserve one object or a few objects,” Brockman said. “Maybe they had a small leak in their house. Or they found this item in an antique market. Now it’s — ‘Can you please help all of us because entire neighborhoods have burned down?’ We’re not dealing with isolated art works. We’re dealing with a whole house of artworks and cherished belongings.”

An effective approach to that requires good connections, planning, communication and some MacGyver-like creativity.

“Being of service feels really good,” Schindler said. “In that first week after the fire, as things were kind of easing, the focus shifted to air quality. I was so anxious, I wasn’t sleeping. So I pulled together an annotated bibliography.”

Because, of course. Wouldn’t an annotated bibliography be on your to-do list?

“I’m such a WUDPAC-rat,” Schindler said. “I have resources and I know they’re reliable. I know how to share them. I can’t help everyone in the city, but this was a helpful way to channel my nervous energy into this document, attempting to get information into the hands of folks who needed it.”

It was three or four pages’ worth of credible, accurate information, connections, links to tutorials — a roadmap to a path forward.

“We want to help people understand that a lot of basic things they can do themselves,” Brockman said. “And we want to offer as much support as we can.”

Support for the helpers, help for the objects

It wasn’t long before they heard from Debra Hess Norris, director of the WUDPAC Program.

“She asked ‘How can UD help? What can we do to support you?’” Schindler said. “They were able to pull some funds together to send our way. With all of this donated time, that UD support allows us to breathe a little easier.”

That is a powerful aspect of the UD program, Brockman said.

“I feel like I’ve leaned a lot on the support network of the instructors I had in grad school. This is why this program is so great — not just the program, but the support network afterwards.”

Within weeks of the fires, like-minded conservators converged — including others with UD connections, such as Ellen Moody, who earned her master’s in objects and preventive conservation at WUDPAC, and Yulimar Luna Colón, who earned her bachelor’s in art conservation and art history at UD — and Art Recovery L.A. was born.

Brockman built ARLA’s website and produced short instructional videos on how to use PPE and basic remediation treatments. The group has hosted “Instagram Live” events and a “Don’t Toss It” campaign was launched to encourage people to hold on to recovered items in case they could be salvaged.

Soon the first public conservation clinic was on the calendar. And then scores of people were arriving with stuff they had pulled from many different situations.

Not much paper — if any — would survive a fire that burns a structure to the ground. Ceramics and metal objects have a better chance.

“But there are things that are in close proximity to a fire but are not burned,” Brockman said. “Smoke and ash and soot are really bad for everything — for our health and for objects. Things in frames — photos, prints, drawings — have a little layer of protection around them. But if they’re in close proximity to fire, I’ve seen acrylic or Plexiglas framing that warps and you’re worried about the artwork inside. If it’s not framed, it’s a bigger issue.”

Salvaged items were evaluated, vacuums sucked up ash and soot, tears were shed.

One woman brought in a set of bedroom curtains. She had lung problems and wasn’t sure she should keep them.

“We’re not industrial hygienists, but we talked through options,” Schindler said.

The first clinic drew more than 110 objects — baskets, ceramics, mugs, jewelry, a menorah, some ritual objects, books, photos, stuffed animals, a few wall hangings.

“The bigger conversation now is — how are these objects a prompt for storytelling and healing?” Schindler said. “Getting to safety is first, of course — your health is a priority. But why do these objects matter to people? While we are here to talk about storage and handling and treatment, what we really want to hear is what does this object mean to you? What is the story you are rescuing from this rubble?”

The meaning of a mural

Another casualty of these vicious fires was the Pasadena Jewish Temple and Center. The conservative synagogue, more than 100 years old, was burned to the ground in the Eaton Canyon fire.

The Torah scrolls were saved, Schindler said, but little else survived. Only one wall was still standing — but it was especially astonishing. The façade of the wall had burned away, revealing a 25-foot-high mural no one knew was there.

“It’s very faint,” Schindler said. “It has imagery of people playing instruments, with donkeys, animals, trees all around. It’s hard to see and figure out what is going on.”

Schindler’s partner, who is in rabbinical school at Hebrew Union College, connected Schindler with the board of the synagogue and Schindler called Kiernan Graves of Site & Studio Conservation, a conservator who specializes in wall paintings.

A couple weeks after the fire, they learned the first rain was in the forecast, so they went to the site to protect the mural by putting Tyvek sheeting over it. They were fighting the clock and the process was more complicated than they anticipated.

“That was a really hard day,” Schindler said. “It was physically and emotionally exhausting to be literally walking through rubble and kicking up soot. The playground was melted. It was devastating. I was in full hazmat with a face respirator and goggles, layers of gloves. It drove home to me the importance of personal protective equipment (PPE).”

Later, they raised funds to rent a cherry picker — also known as a boom lift — so they could reach the upper parts of the mural, secure the Tyvek tent and do much closer inspection. They planned to do more research on the history of the site and the origin of that mural.

But, alas, the site had to be cleared of hazardous materials and the wall was demolished by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers as part of that remedial process.

Though their skills can often make museum pieces out of what seems like a lost cause, conservators must work within the constraints of finances, time and the owner’s priorities. The synagogue had identified health, safety and rebuilding as its priorities for the site, and the wall’s demolition made sense within that context, Schindler said.

“We were able to salvage some pieces and we have high-quality images, but the mural is no longer intact,” Schindler said. “We will continue our research and figure out what next steps can be done with the salvaged pieces.”

Preparing for future crises

All of these experiences and new connections provide a strong foundation for what will surely be part of the future — more crises.

“The unfortunate truth is this: climate change,” Schindler said. “This will be one of many future disasters. There will be floods, winds, mudslides. Being an established group will allow us to be a resource for people as we go forward.”

It’s essential for everyone to prepare for the future, to consider plans and ask the hard questions ahead of time.

“Everyone in L.A. is now familiar with a ‘go bag,’” Schindler said. “They know where their passport is, their prescriptions and bottles of water. But what things are you going to salvage? Do you have insurance? What does your policy cover? Do storage containers matter?”

The WUDPAC program was an excellent proving ground not only for techniques of conservation, but also in “soft skills,” Schindler said, pointing to the DELPHI (Delaware Public Humanities Institute) program as an example.

“When I attended, it was a two-week program,” Schindler said. “It was during the COVID pandemic, so it was all on Zoom. We came up with personal mission statements, worked on our ‘elevator pitches’ and did a little media training. All of that has been helpful to me in this moment and in my career in general.”

Contact Us

Have a UDaily story idea?

Contact us at ocm@udel.edu

Members of the press

Contact us at mediarelations@udel.edu or visit the Media Relations website