Monitoring biological diversity

Photos by Evan Krape | Photo illustration by Jeffrey C. Chase August 14, 2025

UD student examines pollen in honey to understand the plants bees prefer

Editor’s note: Every year, hundreds of undergraduates at the University of Delaware pursue research under the guidance of a faculty mentor, especially during the summer months. Such experiences provided by UD — a nationally recognized research university — can be life-changing, introducing young scholars to a new field, perhaps even the path to a future career, as they uncover new knowledge. These spotlights offer a glimpse into their world.

It’s that time of year, when we witness bees buzzing from plant-to-plant, pollinating everything from flowers to trees to agricultural products like vegetables, fruits or nuts. This activity can lead to honey when a honeybee takes pollen and nectar back to the hive. It also supports the diversity of other things in the bee’s ecosystem, from plants to animals to insects.

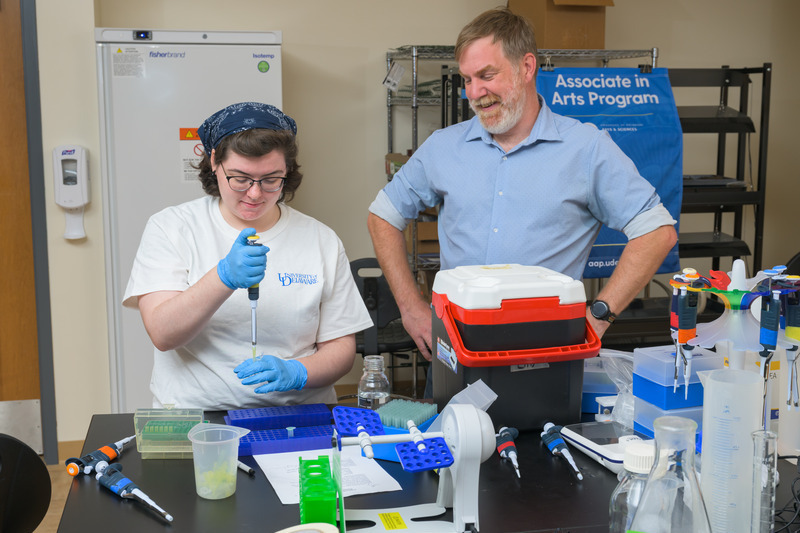

Wilmington, Delaware, native Jillian Haverly is a senior biological sciences major, with a concentration in cellular and molecular biology and genetics and minors in writing and forensic science. Under the advisement of Daniel McDevit, an associate professor with UD’s Associate in Arts Program (AAP), Haverly is studying which plants bees collect their nectar from by examining the DNA in honey samples on UD's Wilmington campus. Haverly began her UD education in the AAP, taking advantage of UD’s Flex Pathway. Her summer experience was funded through the Delaware INBRE Summer Research Program.

Q: Why did you want to pursue this? What intrigues you about the topic?

Haverly: It's interesting that the pollen in bee honey can be used to determine what plants bees get their nectar from. It's a way of going back in time and seeing what path the bees took to make their food. Do bees prefer one flower to another? How far will the bees fly to access the nectar to make honey? How do the bees change the plants they visit from hive to hive, and how do these plant selections change over time? To me, it shows how something so small can be so complex.

Q: Why does research like this matter?

Haverly: It is essential to understand which plants bees frequent so we can learn about the path the bees take to produce their honey. This will tell us how far the bees are traveling from the hive to collect their nectar and if the plant they are visiting is only located within a specific area of the bees’ radius. If the bees tend to prefer a flower situated farther away, rather than nearby flowers, this is important information for beekeepers. This way, they can have a better understanding of their colony and act accordingly, like planting the preferred flower nearby.

For example, my first impression was that city bees did not do as well as rural bees, but this is untrue. City bees actually thrive due to the diversity of plants found in cities in such a densely packed area, whereas rural bees have to fly further to get to different plants. To cut down on bee flying time, beekeepers can move certain plants the bees favor closer to the hive.

Q: What does your daily research entail?

Haverly: Although it is indoors, there is a beehive on the roof of the Community Education Building on UD’s Wilmington Campus. We collect the raw honey from the beehive, then extract the pollen from the samples in the lab. To do this, we mix the honey with water in small tubes and then spin the tubes in a centrifuge machine. This creates a pollen pellet at the bottom of the centrifuge tubes which we can then separate from the honey-water mixture. Then, through a series of steps, we extract and multiply the DNA from the pollen sample. We confirm that there is usable DNA in the sample by using a PCR (polymerase chain reaction) machine that creates more copies of genetic material, in this case, DNA. We then separate the DNA molecules using a technique called gel electrophoresis. When we get usable DNA, we sequence it to determine the nucleotide order (A-T G-C pairs) or code that will help us identify which plant the pollen came from. When we can confidently say a sequence belongs to a certain plant, we can say that the bees who made the honey visited this plant. These findings will hopefully give beekeepers a better understanding of their hives and the path their bees take to gather nectar.

Q: What is the overall goal with this project?

Haverly: The project is in its infancy, so there are two goals. The first goal is to determine how we can find what plants bees get nectar from. The other goal is “let's find the kinks and iron them out.” We are trying to figure out if the process we are using to determine the plants bees’ frequent works or not. We are also doing these experiments to see if we can find better ways to carry out this research down the road.

Q: What’s the coolest thing about being involved in this project? Have you had any surprising or especially memorable experiences?

Havelry: For me, the coolest thing about this project is working with the honey, a food I already really like, and learning so much about it. Also, I enjoy learning how to use laboratory tools, such as pipettes used for transferring liquids, and learning how to create materials like gel used in a lab setting.

Q: Is there anything you’ve discovered about yourself and your career goals as you’ve worked on the project?

Haverly: I have discovered that I am more interested in research than I originally thought, and this research has shown me that ecological science is really cool. I was always interested in small, microscopic things in biology, but ecology is more about the organisms and animals we can see. In the past, genetic and microscopic biology seemed like a whole different world to explore, while ecology did not. But because of this research, I've learned that ecology is another world to explore, and a world that is a lot easier to access. What mainly interests me is how everyday animals we see lead very different lives than we humans do.

Before this research, I was somewhat interested in research, but not enough to consider it for a career. Through what I’ve experienced this summer, I would definitely consider research as a career choice. This adds another possibility to my future and gives me yet another academic interest to pursue.

Q: What do you enjoy doing in your spare time?

Haverly: In my free time, I enjoy playing video games, watching YouTube videos on extinct species, writing and drawing.

Contact Us

Have a UDaily story idea?

Contact us at ocm@udel.edu

Members of the press

Contact us at mediarelations@udel.edu or visit the Media Relations website