Poet for all

Photos by Evan Krape and iStock January 24, 2022

Scotland’s Robert Burns inspires readers and singers, dancers and eaters

Editor's note: This story was originally published on Jan. 24, 2020, before the restrictions of the pandemic limited social gatherings. But even COVID-19 can't dampen the collective spirit of Robert Burns' devotees, who are still finding ways to safely gather and celebrate the poet. On Tuesday, Jan. 25, kilted fans from within the UD community and beyond will once again dance, sing and raise their glasses in honor of Scotland's national bard.

Rock star. Ladies’ man. Revolutionary.

This isn’t typically who you’d expect to find in the 18th-century poetry section of your local library, but Robert Burns wasn’t your typical poet.

“He was a classic, charismatic bad boy,” said Devon Miller-Duggan, assistant professor of English at the University of Delaware and the author of four poetry collections.

Sure, Burns was “bad” in the traditional sense. He loved to party, and he fathered 12 children from multiple women. But he was also “bad” in that he bucked societal expectations.

Born in 1759 to farmer parents in Scotland, Burns was a brilliant writer who tackled big themes — love, nature, classism — in humorous, musical verse. And he did so in the vernacular of the common, hardworking Scotsman. Burns rejected the scholarly style that was all the rage among his contemporaries. Instead, he straddled the line between high-brow and low-brow. This earned him a cult-like following in his home country and beyond — American presidents and pop stars have cited the bard as a muse. To this day, every Jan. 25, traditional Scottish celebrations called Burns Suppers or Burns Nights are held around the globe to honor the birthday of Scotland’s national poet.

For some at UD — a university founded by a colonial scholar of Scottish descent — Burns’ legacy is never far from mind.

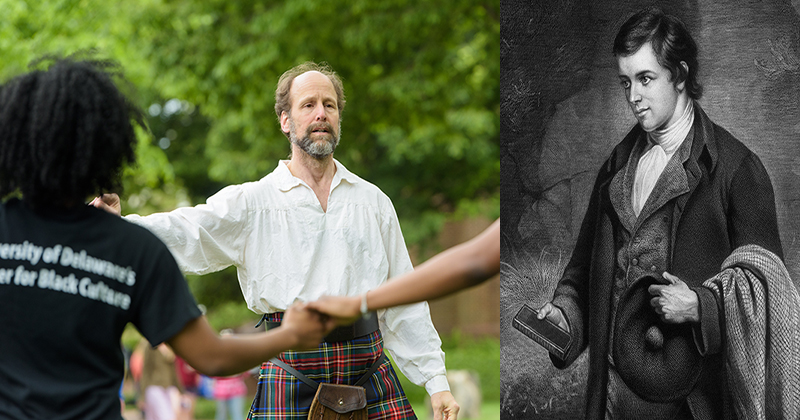

Consider Terry Harvey. He is a UD associate professor of computer and information sciences who fell in love — while he was an undergraduate at UD 36 years ago — with Scottish country line dancing, a precursor to American square dancing that relies heavily on Burns poems set to music. A friend in Harvey’s residence hall had spotted a flyer on a telephone pole advertising nearby classes, and she’d asked him to join.

“It felt like I’d been looking for this my whole life,’” said Harvey, a self-described “mutt” without any Scottish ancestry of his own. “I got hooked. The activity is a blast, and the people are warm and welcoming.”

Plus, the traditional dress adds a little something extra.

“It feels weird to dance in pants,” Harvey said. “Kilts are heavy, and they provide a lot of feedback on technique when they swing.”

Now a certified instructor of Scottish country dance — an esteemed title that requires a four-year apprenticeship — Harvey teaches and takes classes all over the world, including Scotland. And he belongs to a 150-strong contingent of local Scottish dancers, approximately 30 of whom are students, alum or staff at UD. He also advises the Scottish Country Dance Club on campus, which rehearses but doesn’t perform — this is meant to be a social activity only.

"It’s team based, it’s exercise and it’s a great way for students to have fun on a Saturday night without drinking,” Harvey said. “It’s also a great equalizer. When you’re dancing, you don’t know who’s Democrat or who’s Republican. And it doesn’t matter what you do for a living. I’ve danced with bus drivers and the director of the U.S. Naval Research Laboratory.”

This idea that no one is better than anyone else — regardless of race, position or gender — is a common, ahead-of-its time theme in Burns’ work. And he often poked fun at upper-class elites who disagreed. He wrote one satirical poem to the louse he spotted crawling on the fancy hat of a well-to-do lady in church, questioning whether the “crowlie ferlie” (ie, “crawling hair fly”) shouldn’t be feasting on a poor lady instead.

Among those inspired by these egalitarian beliefs? Abraham Lincoln, who became enamored with the poetry as a teenager. Later, while practicing law, he memorized every verse. By the time abolitionist Frederick Douglass was reciting Burns’ poems to the president, urging him toward the emancipation of black slaves, Lincoln was already well convinced of what he called the bard’s “transcendent genius.”

According to Miller-Duggan, if Burns were around today, he’d likely still be a political force.

“I’m pretty sure he’d be all for the Scots saying ‘bye-bye’ to England,” she said. “Especially with Brexit.”

Burns’ cultural influences abound. His most famous poem — Auld Lang Syne — is sung at New Year’s Eve parties around the world, and it provides the soundtrack to scenes in Sex and the City and When Harry Met Sally. Bob Dylan has cited the Burns poem To a Red, Red Rose as his greatest influence, while Michael Jackson’s Thriller music video was reportedly inspired by Burns’ epic poem, Tam O’Shanter, about a man chased by ghouls through a graveyard. The title of John Steinbeck’s novel Of Mice and Men? That came from To a Mouse, a poem in which, after accidentally killing a mouse, Burns ruminates on how humans have no right to feel superior when we have so much in common with a lowly rodent.

“The best-laid schemes of mice and men go often askew,” reads the English translation. “And leave us nothing but grief and pain, for promised joy!”

Given all we owe him, “Burns is definitely underappreciated outside of his cult following,” said Shannon McNaul, a senior in UD’s chemical engineering program and president of the Scottish Country Dance Club. She and her fellow club members will attend a Burns Supper on Saturday, Jan. 25 at the Arden Gild Hall, north of Wilmington. “The event is a celebration of life. The joy and community on display come from Burns’ spirit, and it’s really powerful.”

McNaul, it should be noted, plans to eat the Burns Night haggis, a Scottish dish traditionally made of sheep entrails and organs. The translation of Burns’ poem Address to a Haggis, reads: “Good luck to you and your honest, plump face, Great chieftain of the sausage race! Above them all you take your place, Stomach, tripe or intestines… warm, steaming, rich!”

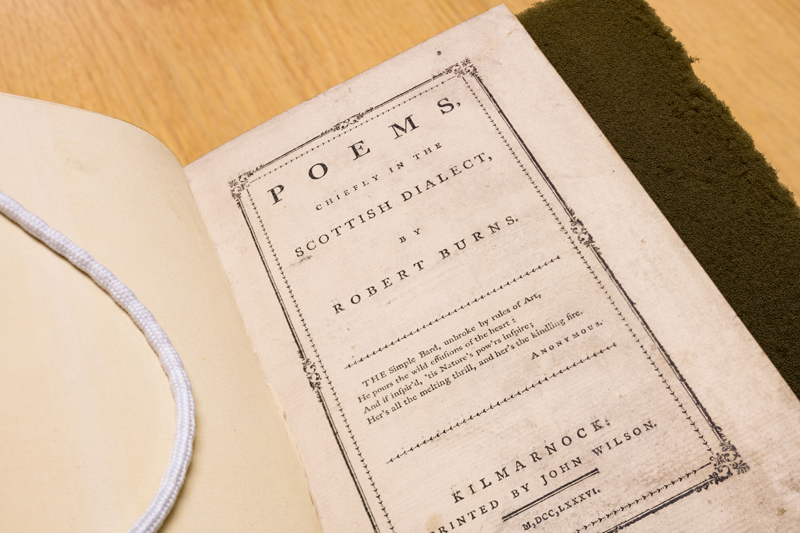

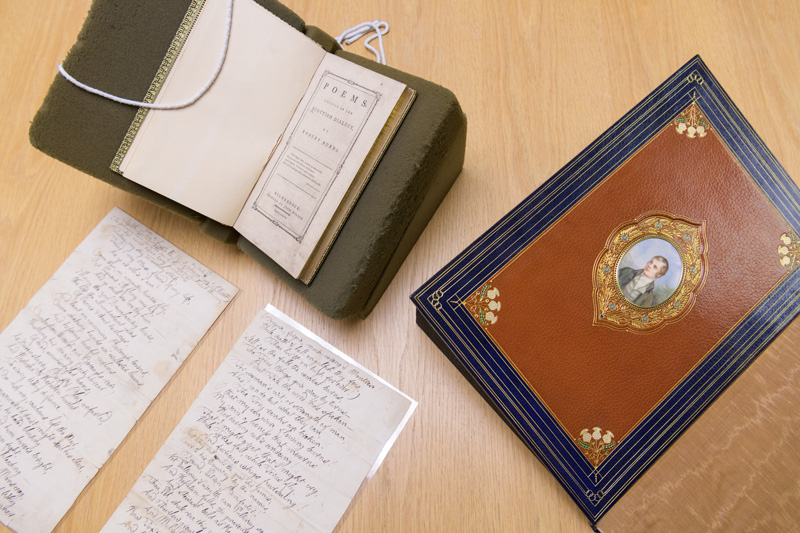

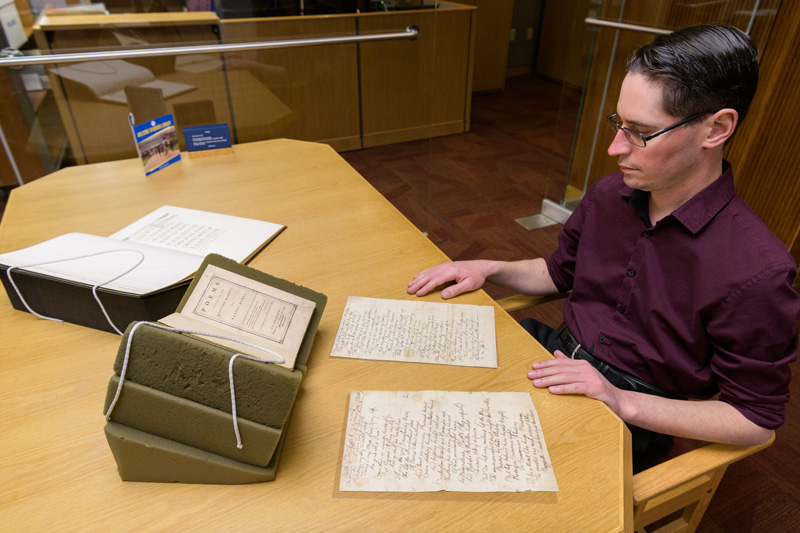

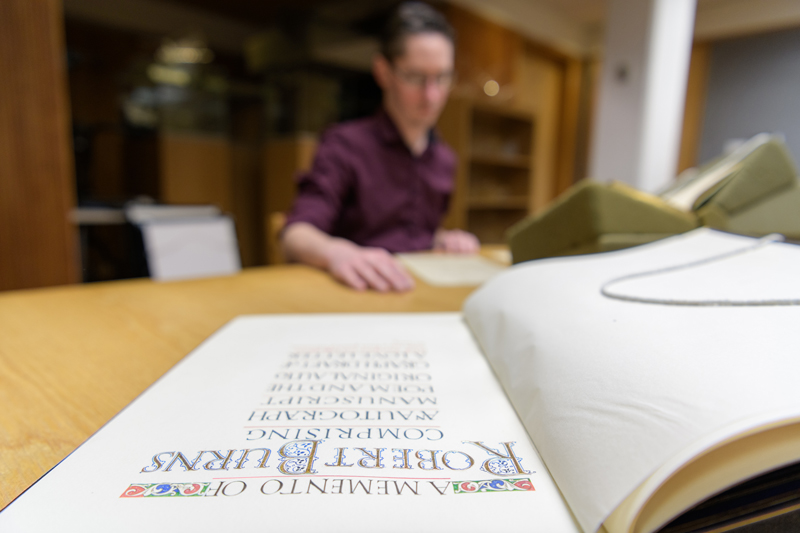

For students looking to learn more, Morris Library's Special Collections is home to a first-edition copy of Poems, Chiefly in the Scottish Dialect, the book responsible for launching Burns, then 27, to celebrity status. Out of an original print run of 612, it is one of only 84 known copies remaining around the world.

“It’s pretty spectacular,” said Alex Johnston, associate librarian and coordinator for books and printed materials in Special Collections. “It’s an artifact of the 1780s.”

The pages have a handmade aspect to them, since they were printed on a handpress. In other words: one letter at a time, using an engraving tool. This left much room for error if the technician, say, lost his place or dropped a letter without realizing. In the back of the book is a glossary of Scottish terms (like “rowt” for bellow or “nowte” for cattle) that Burns wanted to celebrate.

The library is also home to original, one-of-a-kind poems and love letters. Printed on paper stock likely made of melted-down clothing, these allow the reader to see how Burns revised as he worked.

“The lover who is certain of equal return of affection is surely the happiest of men,” reads one such letter addressed only to ‘Madam.’ “But he who is prey to the horrors of anxiety and dreaded disappointment is a being whose situation is by no means enviable.”

At least, according to Miller-Duggan, it’s worth stopping by to peruse the collection, even if you’re not much for history, Scottish culture or even poetry.

“We should read Burns because he was a master of the ballad and of human emotion,” she said. “And we should read Burns because he delights. We need more delight.”

Contact Us

Have a UDaily story idea?

Contact us at ocm@udel.edu

Members of the press

Contact us at mediarelations@udel.edu or visit the Media Relations website