- Rozovsky wins prestigious NSF Early Career Award

- UD students meet alumni, experience 'closing bell' at NYSE

- Newark Police seek assistance in identifying suspects in robbery

- Rivlin says bipartisan budget action, stronger budget rules key to reversing debt

- Stink bugs shouldn't pose problem until late summer

- Gao to honor Placido Domingo in Washington performance

- Adopt-A-Highway project keeps Lewes road clean

- WVUD's Radiothon fundraiser runs April 1-10

- W.D. Snodgrass Symposium to honor Pulitzer winner

- New guide helps cancer patients manage symptoms

- UD in the News, March 25, 2011

- For the Record, March 25, 2011

- Public opinion expert discusses world views of U.S. in Global Agenda series

- Congressional delegation, dean laud Center for Community Research and Service program

- Center for Political Communication sets symposium on politics, entertainment

- Students work to raise funds, awareness of domestic violence

- Equestrian team wins regional championship in Western riding

- Markell, Harker stress importance of agriculture to Delaware's economy

- Carol A. Ammon MBA Case Competition winners announced

- Prof presents blood-clotting studies at Gordon Research Conference

- Sexual Assault Awareness Month events, programs announced

- Stay connected with Sea Grant, CEOE e-newsletter

- A message to UD regarding the tragedy in Japan

- More News >>

- March 31-May 14: REP stages Neil Simon's 'The Good Doctor'

- April 2: Newark plans annual 'wine and dine'

- April 5: Expert perspective on U.S. health care

- April 5: Comedian Ace Guillen to visit Scrounge

- April 6, May 4: School of Nursing sponsors research lecture series

- April 6-May 4: Confucius Institute presents Chinese Film Series on Wednesdays

- April 6: IPCC's Pachauri to discuss sustainable development in DENIN Dialogue Series

- April 7: 'WVUDstock' radiothon concert announced

- April 8: English Language Institute presents 'Arts in Translation'

- April 9: Green and Healthy Living Expo planned at The Bob

- April 9: Center for Political Communication to host Onion editor

- April 10: Alumni Easter Egg-stravaganza planned

- April 11: CDS session to focus on visual assistive technologies

- April 12: T.J. Stiles to speak at UDLA annual dinner

- April 15, 16: Annual UD push lawnmower tune-up scheduled

- April 15, 16: Master Players series presents iMusic 4, China Magpie

- April 15, 16: Delaware Symphony, UD chorus to perform Mahler work

- April 18: Former NFL Coach Bill Cowher featured in UD Speaks

- April 21-24: Sesame Street Live brings Elmo and friends to The Bob

- April 30: Save the date for Ag Day 2011 at UD

- April 30: Symposium to consider 'Frontiers at the Chemistry-Biology Interface'

- April 30-May 1: Relay for Life set at Delaware Field House

- May 4: Delaware Membrane Protein Symposium announced

- May 5: Northwestern University's Leon Keer to deliver Kerr lecture

- May 7: Women's volleyball team to host second annual Spring Fling

- Through May 3: SPPA announces speakers for 10th annual lecture series

- Through May 4: Global Agenda sees U.S. through others' eyes; World Bank president to speak

- Through May 4: 'Research on Race, Ethnicity, Culture' topic of series

- Through May 9: Black American Studies announces lecture series

- Through May 11: 'Challenges in Jewish Culture' lecture series announced

- Through May 11: Area Studies research featured in speaker series

- Through June 5: 'Andy Warhol: Behind the Camera' on view in Old College Gallery

- Through July 15: 'Bodyscapes' on view at Mechanical Hall Gallery

- More What's Happening >>

- UD calendar >>

- Middle States evaluation team on campus April 5

- Phipps named HR Liaison of the Quarter

- Senior wins iPad for participating in assessment study

- April 19: Procurement Services schedules information sessions

- UD Bookstore announces spring break hours

- HealthyU Wellness Program encourages employees to 'Step into Spring'

- April 8-29: Faculty roundtable series considers student engagement

- GRE is changing; learn more at April 15 info session

- April 30: UD Evening with Blue Rocks set for employees

- Morris Library to be open 24/7 during final exams

- More Campus FYI >>

Click here to access an audio or video podcast of this event.

4:11 p.m., Sept. 26, 2008----When Arctic explorer Elisha Kent Kane died in 1857, his was the largest funeral, up to that time, in American history. His funeral cortege would take three weeks to cross the country and would be met by thousands of mourners.

So who was Kane, and why did he captivate a nation?

Michael Robinson, author of the Coldest Crucible: Arctic Exploration and American Culture, began unraveling the mystery on Wednesday evening, Sept. 24, at the University of Delaware. His lecture, fittingly delivered on one of the world's International Polar Year Days, was the latest presentation in UD's William S. Carlson International Polar Year Events, named after the University's president from 1946-50, who was a polar explorer.

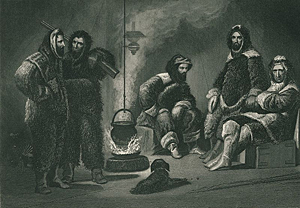

During the talk, Robinson projected historic images of American polar expeditions, which coincide with “Poles Apart: Photography, Science and Polar Exploration,” an exhibition under way at the University Gallery through Dec. 7.

At only about 5 foot 5 inches tall and 120 pounds, Kane was the antithesis of the larger-than-life, Schwarzenegger-esque polar explorer imagined by many of us. He was fragile, afflicted by rheumatic fever and prone to seasickness. Yet Americans “were obsessed” with him, Robinson said.

Kane was a medical officer on the first official U.S. expedition to the Arctic. The U.S.S. Grinnell set sail in 1850 to search for British explorer Sir John Franklin, who had left England's shores in 1845 in search of the fabled Northwest Passage.

After the U.S.S. Grinnell returned home, unsuccessful in its mission, Kane organized a second expedition to find Franklin, which he later wrote about in his book, Arctic Explorations, regarded by Robinson as the “Harry Potter of the 19th century.”

Robinson noted that even though Kane failed--Franklin was not found, half the crew refused to continue on, and he had to abandon ship off Greenland--he was treated as a hero.

“Escaping the jaws of death impressed Americans. But there's more to it than that,” Robinson said, reminding the audience that at this time in history, “things are heating up in America. There was the ambiguous status of American territories and whether they would become slave or free states,” he said. “There already is fighting in the Kansas territories....In a way, the Arctic was a place where northerners and southerners could all agree--he [Kane] represented Americans without the mess of empire, of calling it free or slave.”

In the late 19th century, the focus shifted to finding the North Pole, with voyages like those of George Washington Delong, leader of the Jeannette Expedition, which, subsidized by New York newspapers, was the first to have corporate sponsorship.

Engaging the theory that a vessel could drift north by becoming part of the ice pack, the U.S.S. Jeannette did just that, drifting for a year before it was crushed by the ice. The expedition then faced the daunting challenge of reaching the Siberian coast in hopes of rescue. Ultimately, 17 of the crew, including Delong, died; seven survived.

The first truly scientific U.S. polar expedition was the Greely Expedition, one of two groups sent to the Arctic by the U.S. as part of the first International Polar Year.

For two years, Greely and his party collected geographic and meteorological data from Fort Conger on Ellesmere Island, Canada's northernmost point. After the International Polar Year ended in 1883, however, Greely sought to continue north. The voyage did not go well, and crew members died of starvation.

Upon his rescue in 1884, Greely, emaciated, uttered a telling comment concerning the expedition's true purpose: “Here we are, dying like men. Do what I came to do, beat the best record.”

The polar quest further escalated to become a form of sport in 1906 when Walter Wellman, a reporter for a Chicago newspaper, decided to send a motor balloon over the North Pole. His strategy was simple: don't navigate through the ice, go over it. But powered solely by a 50-horsepower engine, the balloon could not maintain a course in the Arctic wind.

Explorers Robert Peary and Frederick Cook beat him to the North Pole in 1909 in a controversy that still rages today about who got there first.

The odysseys of the polar explorers not only tell us much about Americans in the 19th century, Robinson said, but also shed light on present-day American culture, particularly relating to the rumblings of a new race--to other planets.

In 2004, President Bush announced the latest vision for space exploration--a manned mission to Mars.

The question is, what is the objective of sending human beings into space, to do space exploration?” Robinson asked.

“I think right now is a moment of soul-searching in America,” Robinson said. “What they're not asking is, why do we need to be doing this?”

Earlier in the evening, speaking on behalf of UD's seven colleges who are co-sponsoring the Carlson series, Robin Morgan, dean of agriculture and natural resources, noted that UD's first agricultural research in the high latitudes occurred in the Matanuska Valley just north of Anchorage in 1949, during Carlson's tenure as UD president.

Today, through UD's nationally recognized study abroad program, Morgan said, students have traveled to Antarctica and, as modern polar explorers, documented their adventures through photographs and blogs.

Article by Tracey Bryant

Photo by Tyler Jacobson