Star power

Photo illustration by Jeffrey C. Chase | Photos by Kathy F. Atkinson and courtesy of NSF–DOE Rubin Observatory January 20, 2026

UD graduate student helps lead global effort to reveal universe’s hidden wonders

From a mountaintop in Chile, the Vera C. Rubin Observatory is preparing to capture the most detailed, decade-long movie of the night sky ever attempted. With the world’s largest digital camera, the size of a small car, the telescope will capture billions of images of our changing universe, unmasking never-before-seen galaxies, exploding stars, asteroids, comets … and who knows what else hiding in the heavens?

Thousands of miles away in the Department of Physics and Astronomy on the University of Delaware campus, doctoral student Tatiana Acero-Cuellar will play a pivotal role in filtering and classifying these images for use by astronomers around the globe. She is developing an AI tool — a deep convolutional neural network inspired by how the brain recognizes patterns — to rapidly analyze the images and home in on objects of interest.

The neural network approach uses multiple or “deep” layers that learn to identify increasingly complex features in data. The “convolutional” component refers to the mathematical process that allows the system to first detect simple elements, such as edges, and then build up to recognizing shapes and complete objects.

“Rubin Observatory will collect 1,000 images per night,” Acero-Cuellar said. “We estimate that each image, if printed, would be about as large as a basketball court. Within each image, we expect 10,000 astrophysical bodies to have changed their aspect — their appearance or position. That’s why this tool needs to be as simple and powerful as it can be because the observatory’s goal is to process what it sees within 60 seconds and report everything relevant to the community.”

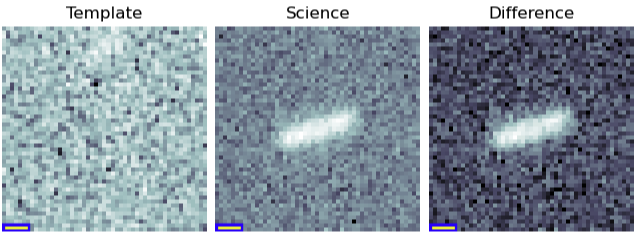

To accurately interpret what Rubin’s camera has captured, Acero-Cuellar’s tool must be trained on more than 200,000 human-inspected images. Is that streaky pattern a comet, or is it a distortion from the camera mount vibrating?

And that’s where citizen scientists can help.

“The Rubin Observatory is built by the community for the community,” said Acero-Cuellar, who is a Unidel Distinguished Graduate Fellow at UD. “Through our citizen science program — the Rubin Difference Detectives — we invite everyone to join our groundbreaking project and help make discoveries possible.”

Citizen scientists wanted

Already, more than 1,600 volunteers have signed up for the Rubin Difference Detectives on Zooniverse, which at nearly 3 million volunteers strong, bills itself as “the world’s largest platform for people-powered research.” It brings volunteers together to assist professional researchers. No specialized background or expertise is required.

“Ideally, all the images that Rubin Observatory collects would be beautiful stars and other objects in the sky. But because computers make mistakes, there are errors in the images,” Acero-Cuellar said.

An error or artifact could result from a cosmic ray impacting the camera, a misalignment in the lens, or other issues.

“So, we have to filter the bad detections from the good, by assigning a score between 0 and 1, with values closer to 1 indicating a good detection,” she said.

To achieve this filtering, the observatory uses an image-processing technique that compares new images with pre-existing “template” images. This technique, known as image differencing, allows for the identification of changing and moving objects.

During the Legacy Survey of Space and Time (LSST), launching this year, the observatory is expected to generate 10 million real-time alerts each night from “transient phenomena” such as exploding stars, pulsating stars, and moving objects ranging from planets, comets and asteroids to human-made satellites.

To participate in Rubin Difference Detectives, visit the Zooniverse website and follow the prompts. Tutorials, a field guide and volunteer blog are available in Spanish, Japanese, Portuguese and Turkish, in addition to English.

While volunteers remain anonymous, their work is not. So far, more than 180,000 images have been classified.

“A team of a few people is not going to be able to do what 10,000 people can do, so we need people across the internet to help us,” Acero-Cuellar said. “My dream is that once we have the data fine-tuned, we will be able to share it with everybody, and with the labels — the scores between 0 and 1 — we will be able to help find supernovas, asteroids and more.”

Images take center stage

Now a doctoral candidate at UD, well on her way to a Ph.D. in physics and astronomy, Acero-Cuellar said she has always enjoyed working with images, even though her bachelor’s degree in physics focused on fundamental forces and fields not visible to the naked eye.

“I prefer things that I can see — that are real,” she said. “Somehow, I always wind up with images.”

It was a summer internship with Professor Federica Bianco in UD’s Department of Physics and Astronomy that drew Acero-Cuellar from her homeland of Colombia to UD in 2021. Her project was to build a machine learning model to classify astronomical images. Bianco, who is a resident faculty member of UD’s Data Science Institute and holds a joint appointment in the Biden School of Public Policy and Administration, served as deputy project scientist of the Rubin Observatory’s construction and is now Acero-Cuellar’s doctoral adviser.

“I am so proud of Tatiana for doing something so impactful,” Bianco said. “She is now recruiting citizen scientists to inspect and label millions of the very first images taken by Rubin Observatory. This citizen science project will help discover the secrets of the ever-changing sky.”

In addition to Acero-Cuellar and Bianco at UD, the Rubin Difference Detectives leadership team includes Eric Bellm, research associate professor of astronomy at the University of Washington, Masao Sako, professor of physics and astronomy at the University of Pennsylvania, and Bruno O. Sánchez, postdoctoral researcher at the Centre de Physique des Particules de Marseille in France.

Contact Us

Have a UDaily story idea?

Contact us at ocm@udel.edu

Members of the press

Contact us at mediarelations@udel.edu or visit the Media Relations website