Celebrating 275 Years

Photo by Kathy F. Atkinson February 02, 2018

Historian Carol Hoffecker reflects on the University of Delaware’s beginnings

The University of Delaware traces its roots to the school founded by the Rev. Francis Alison in New London, Pennsylvania, about eight miles from the University’s home today in Newark, Delaware.

To mark the 275th year since the University of Delaware's founding, distinguished Delaware historian Carol Hoffecker recently shared her thoughts on the University’s historical beginnings. She also reflected on some of the themes that have continued through the centuries to create the institution of today and inspire its hopes for the future.

Hoffecker, Richards Professor Emerita of History, is a 1960 graduate of UD and was a member of the faculty from 1973 until her retirement in 2003.

Q: Francis Alison’s school underwent several name changes and moves to different locations after its founding, and it wasn’t even called the University of Delaware until 1921. Is it historically accurate to mark 1743 as a milestone?

A: If you’re going back to the beginnings of the institution that would become the University of Delaware, then yes, that’s the date to use. If you’re talking about the legal creation of the University, its charter with that name, then no. But the first heartbeat of the University? That’s Francis Alison’s school.

Q: Historical accounts always emphasize that Francis Alison was a Presbyterian minister as well as a classical scholar. How important was religion in his decision to start his New London Academy?

A: Francis Alison was Scots-Irish, educated in Ireland and Scotland and a member of the clergy before coming to the United States. In that tradition, he had really solid academic training, not only in reading the Bible but reading it in Greek and Hebrew. It was a very mentally challenging and demanding approach to religion, and he wanted to educate other young men in that same way.

He wanted to train them to read the ancient texts and understand the foundations of Christianity as he saw them, in a way that he hoped would lead some of them to become members of the clergy. One of the main reasons he founded his school, I think, was in reaction to what was called the Great Awakening of the 1730s and ’40s.

Q: What was that movement?

A: It spread widely, throughout the Colonies, but it actually began in Delaware with a man named George Whitefield, who landed in Lewes [from England] in 1739. He brought with him a new kind of religious enthusiasm and began preaching to people of southern Delaware, who hadn’t been especially active in churches before. It was a very emotional approach to Christianity, and it became a major factor in the lives of many people who lived in this region.

But one of the critics of this Great Awakening was Francis Alison. He really found everything about it abhorrent because, to him, it was just enthusiasm without any knowledge or education about Christianity and its foundations. In his school, he would demand serious Biblical studies. He wanted to foster academic, intellectually demanding learning.

Q: Alison’s New London Academy had many students in its first class who would go on to great things, including three signers of the Declaration of Independence [George Read, who also signed the U.S. Constitution, and Thomas McKean of Delaware and James Smith of Pennsylvania]. How remarkable was this?

A: Francis Alison was teaching classical languages, as well as subjects like philosophy and ethics. There weren’t many schools at that time, certainly not in this area, where students could get that kind of very demanding education. So his students, and especially that first class, were really the intellectual elite.

And he wasn’t just training people who were going to be Presbyterian ministers. He was training people who were going to be sitting in the pews too, and who would go on to have very distinguished careers as lawyers and judges and civic leaders.

Q: Alison actually moved to Philadelphia in 1752, but the school he founded continued through various name and location changes. Did his influence and interest continue?

A: Yes, I think so. I think his interest continued, although he also had responsibilities at other schools and as a minister.

I think there was a time when it stopped being particularly Presbyterian. Once people recognized that the way to get ahead—the way for their sons to get ahead—in life was to get a good education, they looked around and saw that the place where that was available in this area was the school in Newark. [The school moved to Newark in the 1760s and was chartered as the Academy of Newark in 1769.] That’s when it started attracting a wider range of students.

Q: The University today values innovation, and it sounds like Francis Alison could be considered an innovator himself in many ways because he started the kind of school that just didn’t exist in this area at the time. Is that one way to view him, in addition to his accomplishments as a scholar?

A: I think the whole history of the University of Delaware, beginning with Francis Alison, is about innovation and change.

History is all about change; if things didn’t change, you wouldn’t need it. It’s really about how people foresee and adapt, and that’s especially so with the creation and involvement of schools and universities. You see needs, and you adapt. In a sense, you’re always creating a new world.

Looking at the University today, I see it continuing to adapt and change and develop. I’ve been so impressed, especially in terms of opportunities for women and minorities. I see innovation, and that’s a good thing—not resting on your laurels but continuing to grow and expand in this new environment.

Q: Has this been a theme throughout UD’s history?

A: Yes, I sincerely believe that. I’ve looked at some leaders through the years who were real innovators:

There’s Francis Alison, of course.

Willard Hall [an original trustee of Newark College, chartered in 1833], who came from Massachusetts to a state [around 1803] that didn’t have any real public schools or training for teachers, and he brought ideas to Delaware about the importance of public education. That would go on to be really significant later in starting the Women’s College, in educating women in order to produce the teachers for the public schools. And the University of Delaware has ever since been a major factor in public education in the state.

H. Rodney Sharp and P.S. du Pont, because it was their financial support that helped the growth of the sciences and also the development of the University’s physical facilities. The construction of buildings [beginning around 1915] on The Mall [now called The Green] also brought the Men’s and Women’s Colleges closer together.

Emalea Pusey Warner, who was an activist in the community and really beat the drum for the creation of the Women’s College [in 1914]. You know, it didn’t become the University of Delaware until the Men’s College and the Women’s College got together. And that didn’t happen until 1921—later than many students today might think.

Q: Where do you see UD heading? Is that an appropriate question for a historian?

A: Absolutely appropriate. The point of studying the past is to show how it led to the future, how it produced the future from its time. And that’s true no matter what kind of history you’re studying.

I think one of the things you can say about the University of Delaware is that it’s always stayed a step ahead in producing students who are capable of moving on and fulfilling the needs of their time, and as long as it keeps doing that it will continue to be successful.

For example, I know there’s an emphasis today on entrepreneurship. When I was a student, no one thought about entrepreneurship. We all wanted to go work for a company like DuPont. The big companies were the entrepreneurs, and we were going to be the workers. Today, in the current situation, we’re evolving into a time when starting your own business is a real career path for many people.

History is about change, how people foresee and adapt. That’s especially so with a university; It can direct the development of society.

Q: You’ve had such an impressive career. After you graduated from UD and went to Harvard for your Ph.D., you must have had many options. Why did you choose to come back to Delaware to work?

A: I loved Cambridge, and I loved Harvard. I did my doctoral dissertation on Harry Truman. The dissertation was OK, but I couldn’t put my heart into it. I just knew that I wanted to study Wilmington. So I contacted Hagley [Museum] and asked if they had a scholar position.

That was around the time of the 1968 riots in Wilmington, a time of extreme racial tensions, and I wanted to understand how this had all come to pass. I was interested in how Wilmington had undergone such dramatic changes in the nature of its employment and housing and how that had resulted in changes such as white residents’ hostility to black residents. I wanted to understand how the city had evolved.

I wrote Wilmington, Delaware: Portrait of an Industrial City, 1830-1910. Then I joined the University faculty in 1973 and stayed for 30 years.

More about Carol Hoffecker, Richards Professor Emerita of History

Hoffecker went to graduate school at Radcliffe College and Harvard University, where she earned her doctorate in history. She taught at Northeastern University and Sweet Briar College before returning to her native state as a resident scholar at Hagley Museum and then as a member of UD’s history department faculty.

While at UD, Hoffecker served as president of the Faculty Senate, chairperson of the Department of History and associate provost for graduate studies, in addition to her duties in teaching and research.

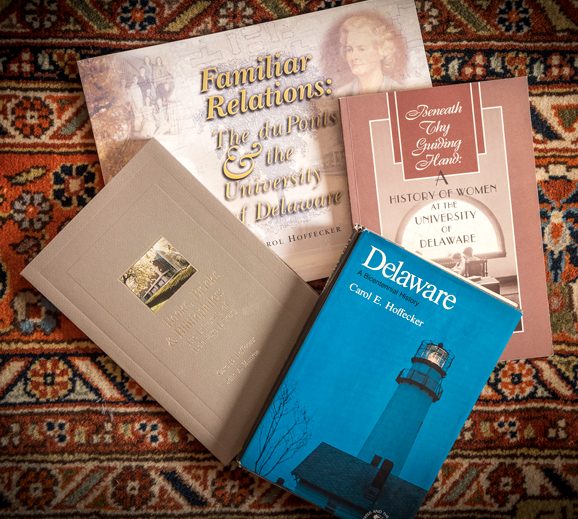

She is the author of several books, including Wilmington, Delaware: Portrait of an Industrial City, 1830-1910; Brandywine Village; Corporate Capital: Wilmington in the Twentieth Century; Delaware: A Bicentennial History; Beneath Thy Guiding Hand: A History of Women at the University of Delaware; Familiar Relations: The Du Ponts and the University of Delaware; Honest John Williams: U.S. Senator from Delaware; Federal Justice in the First State; and—a book familiar to many from their early school days—Delaware, The First State.

At Commencement in May 2009, the University awarded Hoffecker an honorary doctor of humanities degree.

Celebrating 275 Years of UD

In 2018, the University of Delaware celebrates 275 years since its founding in 1743, when Presbyterian minister Francis Alison opened his "Free School" in his home in New London, Pennsylvania. At the dawn of our country’s founding, UD helped change history, and now it’s changing the world. As a time marker in the middle of the milestone 250th and 300th anniversary dates, 275 provides the perfect moment for the University to look back on its roots and past successes; take stock of what it has become today; and stand on the edge of tomorrow to peer into its third century and beyond.

To learn more about UD’s history

The University of Delaware: A History is a comprehensive account by noted Delaware historian John A. Munroe, a UD alumnus and member of the faculty from 1942-1982, who died in 2006. The book was published in 1983, in connection with the 150th anniversary of the 1833 charter granted by the Delaware state legislature to the institution then known as Newark College.

Detailed information about UD’s history is also available on the University Archives website.

The site includes a list of additional resources about UD and its predecessor institutions and materials from a series of exhibitions focusing on the history, activities and accomplishments of the University.

Contact Us

Have a UDaily story idea?

Contact us at ocm@udel.edu

Members of the press

Contact us at 302-831-NEWS or visit the Media Relations website