A less-traveled path to discovery

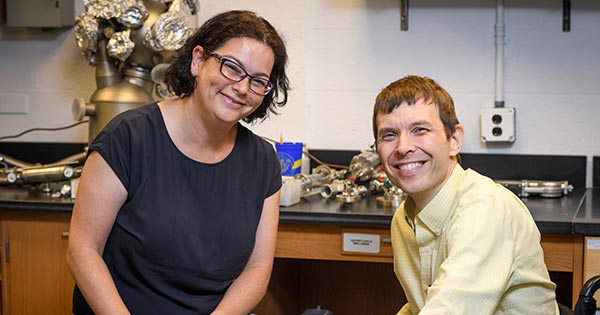

Photo by Kathy F. Atkinson September 19, 2017

UD's Booksh, Rozovsky mentor undergraduate researchers with disabilities

Science? Research? With a learning disability?

Definitely, Emma Kamen would say. Make that "definitely!" - with an exclamation point.

When she found out about the research team University of Delaware professors Karl Booksh and Sharon Rozovsky (chemistry and biochemistry) were leading for students with disabilities, she applied. A National Science Foundation grant supports the Research Experiences for Undergraduates (REU) team.

"I wanted to come here to take this on," she said. "I have struggled with a learning disability, so I have a hard time learning - especially in science. They don't make audio books for textbooks as they do in other areas."

The Marymount Manhattan College student and half a dozen other students from around the country were part of the Booksh-Rozovsky REU team, one of four REU teams at UD this summer. The others included a marine science team at the Lewes campus, a biomolecular engineering team and a mechanical engineering team.

Nationwide, the competitive, 10-week REU program gives more than 1,000 undergrads an opportunity to do research at an institution outside of their home school, giving them access to experts and research opportunities they would not otherwise have.

This was the first year of a three-year NSF grant supporting the Booksh-Rozovsky team and the second such grant the team has received.

Kamen spent the summer in Prof. Andrew Teplyakov's lab, analyzing soot samples from the historic Vanderbilt Mansion in New York's Hudson Valley. Her work will be part of the analysis that helps specialists at the mansion identify the best treatment for the exquisite property there.

For Kamen, the Booksh-Rozovsky team was a great way to dig into research with others who had some sort of disability.

"We all shared our disabilities," she said. "We all had something and we learned how differently things affect us in the field.

"You can't tell by looking at me that I have a disability. In some ways that is to my advantage. In other ways I have to fight for that recognition. This field is so structured, so dense."

Students with a variety of disabilities have been part of this team since it started in 2011 - those with blindness, hearing loss, anxiety disorders, autism, orthopedic disabilities, diabetes, short-term memory loss, learning disabilities, neurological disabilities and arthritis to name a few.

Rozovsky said it was a challenge a few years ago to figure out how to get a service dog into the chemistry lab one student would be working in.

"EHS [Environmental Health & Safety] has been great - and we must credit such partners," she said. "With every new situation they have been on board."

Booksh, who joined UD's faculty in 2006, is a nationally recognized leader in the fight for equal access for those with disabilities. A Fellow of the American Chemical Society who has used a wheelchair since he had a spinal cord injury during his undergraduate years at the University of Alaska-Fairbanks, Booksh chairs the ACS' Diversity and Inclusion Advisory Board and is former chair of its Chemists With Disabilities group. He was instrumental in development of ACS' manual "Teaching Chemistry to Students with Disabilities," now in its fourth edition.

"We're a first-rate university," he said, "and we bring in students that hit all those metrics, the best and the brightest. Those who never got a chance to make it to the front to do research - maybe they are from a smaller school and have no access - we are mining for the gems others overlook."

Booksh said national statistics show that only about 10 percent of high school students who have an Individualized Education Plan (IEP) register with the Disabilities Services for Students office before arriving on campus - a vastly under-reported percentage, he said. He said that has a lot to do with a perception of social stigma related to disabilities. He has been on the front lines working to address that, as chairman of the ACS's Committee on Chemists with Disabilities.

Rozovsky said when they first decided to develop an REU team for students with disabilities, she wasn't sure how students would take to being part of it. She thought they might just stay quiet, afraid to talk about their disability.

"It has been 180 degrees different from that," she said. "They are so relieved to just talk about it and say it out loud and find a community. Diabetes may affect their concentration. There may be underlying psychological issues. But they are dedicated and motivated. We were also lucky that our faculty members were equally dedicated."

It's effort well worthwhile, Booksh said. Some of the world's greatest scientists have had disabilities. For example, Joseph Priestley, who is credited with discovering oxygen, had a speech disability. Humphry Davy was partially blind, but is credited with discovering magnesium, calcium, strontium and barium, among other elements. Thomas Edison had a learning disability and hearing loss.

There must be room for such investigators, who - with appropriate accommodations - have much to contribute.

Connecting with a team of young researchers who share such challenges can provide new support networks and strategies that help students develop resilience, resourcefulness and confidence.

Charlotte Champigny, a biology major at Adelphi University, spent the summer in the lab of Prof. Edward Lyman (physics), analyzing lipid mixtures of membranes and the molecular interactions within them.

Her disability stems from two brain hemorrhages - one in 2006, one in 2009 - that left her with paralysis on her right side.

"Of course, I was a righty," she said with a smile. Now she is a lefty.

Processing words is a challenge for her and as she considers what to say and how to say it she often uses her finger to write the words out on her leg.

"I wanted to do osteopathic medicine," she said, "but my brain works twice as slow and for med school that was going to be tough."

Research has opened other doors - and the summer at UD allowed some time for fun.

"It's great," she said. "The social world and those interactions - I love that, too. At school, I usually study and have physical therapy. When I'm done, I'm exhausted, so I can't go out. Here it has been more relaxed."

Brian Clark, a sophomore chemistry major at Virginia State, came to UD to get some research under his belt and immerse himself in studies. There aren't many chemistry majors at his school, he said, and the UD program gave him an opportunity to participate in high-level research and use the University's resources. He worked with Prof. Zhihao Zhuang and grad student Greg Davidson, spending hours in the lab each day assisting with research on generating a modified protein known as polyUb-PCNA - work that has significant implications for understanding how cells respond to DNA damage.

Clark, who hopes to pursue a doctorate and then work for the FBI, the NSA or the Department of Homeland Security, has rheumatoid arthritis and Crohn's Disease. Pain has been part of his life since he was in fourth grade.

"But you battle through it," he said, and he stays active, working out, playing football, wrestling, competing in track and field. "I'm a highly motivated individual. I'm not going to let anybody define me."

The REU team was a great experience, he said, and he found Booksh an inspiring leader.

"It's tailored to people with disabilities - and we're all overcoming, all doing our best," he said.

The summer had several "firsts" for John Latkowski of Cabrini University, who worked under the supervision of Prof. Robert Opila (materials science and engineering), crunching data to help find an optimal geometry design for an inverse photoemission spectrometer.

He had his first flight while on his way to another first, presenting research at Arizona State University.

The summer experience expanded his options for the future, he said.

"Originally I was planning to go straight to industry," he said. "Now I'm leaning toward graduate school."

Kamen is thinking a lot about graduate school now, too - perhaps in art conservation, perhaps working for the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

Contact Us

Have a UDaily story idea?

Contact us at ocm@udel.edu

Members of the press

Contact us at 302-831-NEWS or visit the Media Relations website