Outwalking a stroke

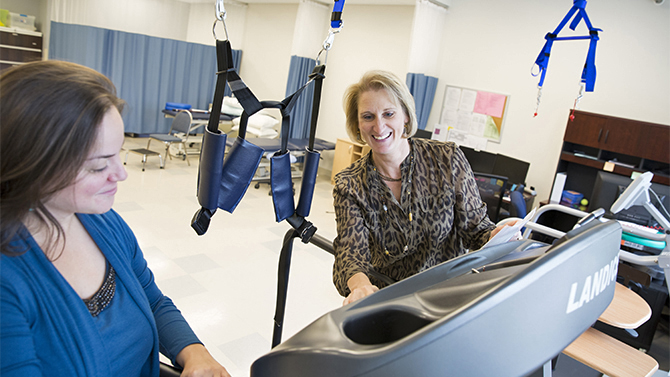

Photo by Ashley Barnas November 02, 2016

Reisman helps stroke survivors translate rehab into real-world steps

“This changes everything.”

There are very few times in someone’s life that those words really mean something. Some are moments of joy — the birth of a child, marrying your best friend or purchasing a home. But other times, like in the case of a stroke, those words are filled with uncertainty, fear and a dim outlook. It is not only a life-changing time for the stroke survivor, but also the caregiver and the person’s entire support system.

One of the biggest areas of impact is physical activity levels. Decreased mobility reduces a stroke patient’s activity level — even below the most sedentary adults. And well-meaning caregivers begin to over-cater to their loved one — sometimes, serving them hand and foot. This newfound lack of movement comes with consequences, including increased risk of recurrent stroke, developing other diseases and even death.

Increasing physical activity is such a common-sense way for all people, not just stroke survivors, to improve things like weight, bone strength, muscle strength and mood. An obvious solution is walking, an everyday exercise that’s not so everyday for a stroke survivor.

Working to help stroke survivors translate their rehabilitation programs into real-world steps is Darcy Reisman, associate professor and associate chairperson of the Department of Physical Therapy at the University of Delaware.

“Working with our physiology colleagues, one of the things we measure is oxygen consumption,” said Reisman. “In stroke patients, just to do their daily activities, they are often functioning at their peak oxygen consumption. No wonder they aren’t doing additional physical activity. We need to find ways to increase their capacity and then work with them to use this capacity in everyday life.”

Prior to receiving her doctorate at UD, Reisman was a practicing physical therapist in neurorehabilitation for seven years. In that time, she worked primarily with stroke and traumatic brain injury patients in an uphill battle to improve their mobility.

“I became frustrated with the level of rehabilitation, which sparked my interest in research and how to improve rehab,” said Reisman.

Initially after someone has a stroke, they are extremely debilitated, perhaps walking only under the guidance of an in-patient PT. As they improve and graduate to outpatient therapy, they are assigned a walking program. Treadmill walking programs are gaining in popularity in PT, but what’s happening after the person gets back into the real world?

“One of the things that is problematic both in stroke and in other populations is the assumption that, if we help people gain strength, mobility, and range of motion, it will naturally translate into more physical activity — that they are naturally going to start using those newfound skills their everyday life,” Reisman said.

But research, including Reisman’s own studies in the STAR Health Sciences Complex, shows that these assumptions are incorrect. Actually, patients are getting better in physical therapy. Yet, when a patient straps on a fancy pedometer (called an accelerometer) and physical activity is measured, researchers see little to no change in the person’s real-world physical activity level.

Additionally, the greatest risk for a stroke is having had a stroke already. The progress under a physical therapist’s expert eye is fantastic, but if they go home and regress to sedentary behavior, chances are the person will require a return to PT or succumb to another stroke.

So Reisman and her UD collaborators, Dave Edwards and Ryan Pohlig, earned a recent grant to evaluate walking interventions that could help change this. She will use a $4.5 million National Institutes of Health RO1 grant to develop and test interventions that improve the overall health and quality of life of persons post-stroke.

UD is the lead site on the three-site study, which includes Christiana Care and the University of Pennsylvania.

“If you look at what’s happening now in physical rehabilitation facilities, very little is being done to improve real-world walking activity,” said Reisman, who is the grant’s principal investigator. “Even as they’re getting better in physical therapy and are able to do more, they still have the same activity level in the real world as before PT.”

But Reisman said she believes a combination of fast walking training and a step activity monitoring program, or SAM, would generate greater improvements in real world walking activity.

Previous work from Reisman’s group at UD provides support for a “combination” approach. She does not expect that one intervention will be superior to the others for all participants; rather, the combined program will be better for those with low levels of baseline walking activity, speed and endurance.

Research will test superiority in preparing people for real-world walking and for whom the combination approach is better.

Research study participation

If you or a loved one would like to participate in the research study, contact Darcy Reisman at dreisman@udel.edu or Martha Callahan at 302-831-6202

Contact Us

Have a UDaily story idea?

Contact us at ocm@udel.edu

Members of the press

Contact us at 302-831-NEWS or visit the Media Relations website