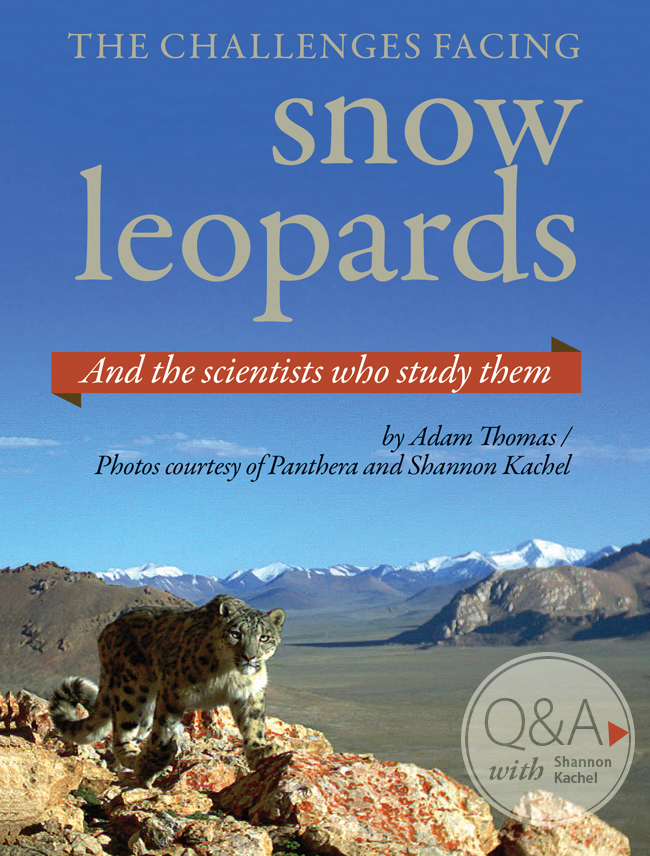

Shannon Kachel, a UD graduate student, spent this past summer setting up cameras in Tajikistan to study snow leopards and wild ungulate populations.

As he lay in a bathtub, seeking shelter from the barrage of mortar attacks just outside his building, Shannon Kachel realized that his summer of studying snow leopards, ibex and Marco Polo sheep in the desolate mountains ranges of Asia was over.

Kachel, a University of Delaware graduate student working with Kyle McCarthy in the Department of Entomology and Wildlife Ecology, was spending the season in the Pamir Mountains of Tajikistan to study snow leopards and wild ungulates, or hooved mammals, to determine all the variables surrounding these species and possibly get an idea about their population sizes. Venturing into the city of Khorog to resupply for the final month of research, Kachel suddenly found himself caught in the middle of a fight between the Tajikistan central government forces and what the government deemed was an illegally armed group.

Kachel wanted to stay and continue his research, but he knew he had to leave.

"I would have stayed because my read of the situation was that it was going to get better," said Kachel. "But I don't know that I would have gotten anything done."

Luckily for Kachel, he had already set up enough cameras in the region—cameras designed to record the movement of the various animals—that he was confident he had enough material for his study.

Researching two distinct areas of the Pamirs, Kachel had placed one set of cameras in a location where the government allows trophy hunting of wild ungulates while informally managing the population for sustainability.

He also set up cameras in a section where it is illegal to hunt the animals and where there is no regulation of the species, but where poaching and overgrazing still threaten the wildlife.

"What I'm doing is comparing those two sites, one for the availability of the ungulate prey, but then the snow leopard populations, as well," Kachel said.

While hunting and poaching is a concern, with the snow leopard population number dropping precipitously over recent decades, Kachel stressed that his research is looking more at the impact pastoral communities have on the species.

"A lot of that population loss results from the typical poaching pressures that we think of from people going out and killing big cats, but a bigger component is competition with pastoral people," Kachel noted.

He explained that as external government food subsidies dried up with the fall of the Soviet Union, it left an artificially high human population in the area based on what the environment could support. In this high and desolate region of the world, the people turned to livestock production and the killing of wild ungulates to sustain themselves.

"The component that I'm addressing is more from the ecological perspective," said Kachel. "The other side of having all these livestock on the landscape is that it reduces the amount of natural prey that's available for snow leopards, and it gets rid of all the forage available for, specifically in my study area, the ibex and the Marco Polo sheep."

Thanks to funding from Panthera, a global wild cat conservation group, and help from the Tajik Academy of Sciences, Kachel spent June and July 2012 traversing the rugged terrain, eventually getting close to 80 cameras set up in an area about half the size of Delaware. "We were hiking around a lot," said Kachel. "Huffing and puffing in that high mountain air."

He explained that the cameras "work based on heat and motion. So an animal that's a different temperature from the background walks by, and the camera starts shooting pictures." Kachel said that since they used two different types of cameras for the study, they put out lures with the cameras to draw in the animals.

"Because the cameras function differently, we needed to make sure that any animal passing by was present long enough to get clear images," said Kachel. "So we used the lure to draw them in and hold their attention. We need clear images so we can identify the individual cats."

Kachel explained that "snow leopards are individually identifiable based on their spots, so we can use our observations of when, where and how frequently individuals are caught by the cameras to build better population estimates that tell us more than a simple minimum count."

The cameras, which were retrieved by a Tajik man once the violence ended, caught pictures and video of two snow leopard cubs, which were highlighted by Reuters and Business Insider.

This past July, after months of analysis, the team reported identifying a minimum of 25 individual snow leopards (vs. 37 identified from fecal DNA). Three-quarters of these cats were found in the hunting concession, where three different family groups (mothers with dependent young) also were photographed.

"This suggests that the local population there is robust and reproductively healthy," Kachel said. "Our back-of-the napkin calculations follow our predictions well—density is three to five times greater where trophy hunting is allowed, following a similar pattern in prey abundance. These results provide compelling initial evidence that trophy hunting can be a ‘win-win' game for conservation and local people."

These findings encourage Kachel about the snow leopard's future.

"I'm actually really optimistic in terms of snow leopard outlook and the prognosis for the species," he said. "The global population estimate ranges from 3,500 to 7,000 animals, and that's a huge range. It could be anywhere in there, so for at least the trophy hunting site, to get the number of images we've gotten back is encouraging to me."

If these preliminary results are borne out, conservationists would gain another tool to protect snow leopards and their prey throughout their range, Kachel said. He recently received a prestigious National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship to continue his studies.