Unearthing New Castle’s

storied past

“If you believe in your heritage; if you believe that the future may learn from the past; if you believe that the question of human liberty and freedom is ‘unfinished business’; if you believe in Democracy; if you believe in the future of this country and of the world ... then I look forward with every confidence to the day New Castle will stand restored and preserved as one more beacon light and symbol of free men.”

— Kenneth Chorley, Colonial Williamsburg President, 1949,

supporting the development of New Castle as the “Williamsburg of the North”

There’s a time-stood-still feeling that permeates old New Castle, with a past so rich and pervasive that walking the cobblestone street is like entering an 18th-century painting.

Buildings have been preserved; gardens restored. But as Lu Ann De Cunzo learned early in her career, “Most people don’t think of themselves as responsible for what’s below the ground.”

And that’s where her story begins.

A professor of anthropology and early American culture, De Cunzo has long been fascinated by the ability to unearth stories of the past. New Castle, which she has studied and excavated for nearly 20 years now, is her research home.

Historic New Castle

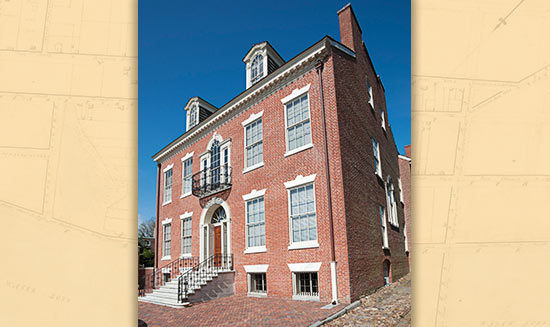

From the Federal architecture of the brick row houses that line the Delaware River, to the building where William Penn was rumored to have entered after first setting foot on American soil, the small port town is a historical gem.

New Castle’s history is rife with tales of conquest and defeat, beginning in 1651, when the Dutch West India Company asserted its claim on the Delaware land. Initially named Fort Casimir, it was prime real estate, serving as a trading post with Native Americans and as fortification against European ships engaged in the fur and tobacco trade. Three years later, it was seized and renamed Fort Trinity by the Swedes as part of New Sweden, only to be conquered by the Dutch the following year and named New Amstel, by England nearly 10 years later who named it “New Castle,” and again by the Dutch in 1683.

“We’ve always known that New Castle was an important port from the history books,” De Cunzo says, “but we never knew what new and alternative perspectives the archaeological record could offer on the town’s cultural history.”

That changed in the early 1990s, as she began collaborating with the Delaware Historical Society, the New Castle Historical Society and the State of Delaware Division of Historical and Cultural Affairs.

“The initial goal was to learn what archaeology might contribute to our collective understanding of the area,” she remembers. But there was a practical purpose, as well: “As organizations and individuals in town continue to develop and build on their land, there was the imminent question of ‘What areas should we avoid?’ ”

Excavating centuries past

For De Cunzo, the project was the epitome of discovery learning, serving as a great educational resource for both students and the broader community.

In 1994, with teams of University and high school students and local volunteers, she began working on the grounds of the Read House, a 22-room, 14,000-square-foot mansion built in 1801–1804 by the son of Delaware’s George Read, signer of both the Declaration of Independence and the U.S. Constitution.

By 1999, she had uncovered more than 70,000 artifacts — Dutch smoking pipes, collections of food bone, ceramics, buttons, bottles, “odd metal things that we couldn’t quite identify.”

“As we started on the Read property alone, we found everything from Native American arrowheads, to remains from the earliest European settlers, to yesterday’s trash,” De Cunzo says.

The vast collection that spanned multiple centuries proved “a wonderful find,” but even more important was “the context; the fact that we had the relationships of things to each other, over time and across space on each site, allowing us to link the artifacts, the landscaping, the building activities and the people.”

And yet it also posed a serious challenge: Where should De Cunzo focus her research?

Preserving colonial history

The colonial period was the era in New Castle’s history with the greatest direct global involvement, as well as a time in which the town enjoyed a unique situation as one of the “middle colonies” that was simultaneously a borderland between New England and the British Chesapeake. And until it was displaced by Dover in 1777, New Castle was Delaware’s capital city.

De Cunzo consequently narrowed in on the colonial period and has since reconstructed a 100-piece collection of colonial artifacts owned by the Delaware Historical Society (DHS). The objects have been featured in exhibits of early Dutch and early Swedish history. Part of the collection remains at UD for research and teaching.

DHS Assistant CEO and Chief Program Officer Michele Anstine regards the collection as a “great tool for the public to understand and picture things they can’t see because they no longer exist.”

The Read House has long told the stories of the families who inhabited the residence. But as Anstine explains, “The stories don’t end with them.”

“The work Lu Ann has done and the questions she has asked are pushing the outer boundaries of our interpretation,” she adds. “Her research allows us to more fully explore the Delaware story, using the property as a tool.”

Discovery Learning

Since De Cunzo began her first excavation in 1994, she has trained nearly 70 high school and college students — including Anstine, who calls her an inspiration and “the reason I finished my master’s at UD” — in excavating, documenting and interpreting archaeological remains on the museum ground.

In spring 2011, as part of a larger cultural landscape report by the DHS to further explore New Castle’s historic Read House, undergraduates in De Cunzo’s “Introduction to Archaeology Field Methods” course participated in documentary research and used ground-penetrating radar to survey the land.

With shovels and trowels, dustpans and dental picks, 19 students spent each Friday of the semester surveying, mapping and excavating the property’s four-acre riverfront lot. Its garden — installed in 1847 and featured in the 1901 issue of House and Garden magazine — remains one of the oldest surviving gardens in the region.

“This isn’t a discipline you can just learn from a book,” says Elanor Sonderman, a senior anthropology major and student in the course. “You can’t really understand stratigraphic sequence or collection and processing until you’re in the ground.”

In addition to the archaeological fieldwork, the students also performedhistorical research on the property and previous owners of the land.

As an anthropology and women’s studies double major, Marissa Kinsey was fascinated to discover a last will and testament that left specific instructions for the living arrangements of the deceased’s wife and slave.

“Objects alone aren’t enough,” Kinsey explains. “Part of the satisfaction of discovering artifacts is learning more about the people who used them.”

De Cunzo agrees.

“Archaeology teaches a process of how to do research,” she says. “It forces the question, ‘What is this thing?’ And more importantly, ‘So what? What did it mean? Why did it matter? Why was it thrown away?’ ”

Marking New Sweden’s 375-year anniversary

De Cunzo, who can now identify nearly 80 percent of what she finds on the New Castle site, has spent nearly two decades answering these questions.

This fall, she is expanding her research to answer them from an internationallens.

As 2013 marks the 375th anniversary of New Sweden, De Cunzo is collaborating with colleagues in the University of Lund in Sweden to organize a virtual conference on the archaeology and material culture of 17th-century Sweden, Native America and New Sweden.

New Sweden itself had a brief history, from 1638 to 1657, but the conference aims to examine the diverse social and cultural groups that contended over and cohabited the colony at a time when Europeans were regarded as “others.”

“We’re entering the larger scholarship and a deeper conversation about colonialism,” says De Cunzo, adding that researchers who have been excavating 17th-century sites in Sweden “give us different perspectives than what we have now.”

Slated for late October or early November 2013, the conference there-fore aims to present cutting-edge research while fostering global approaches to Swedish colonialism in North America.

Because of the six-hour time difference, De Cunzo anticipates the virtual conference would take place simultaneously at the University of Delaware and the University of Lund, with podcasts and resources made available online afterward. She is hopeful it will appeal to scholars across the world researching 17th-century Scandinavian and Middle Atlantic regional colonialism.

“What’s striking about 17th-century Sweden and Scandinavia,” she says, “is that artifacts were largely imported from other parts of Europe.”

That creates a unique challenge for those studying early American settlements — and an incredible opportunity to compare and contrast artifacts from homecountries and the New World.

“In New Castle, you had a new community of Europeans all using the same things,” De Cunzo explains.

So then, what’s Swedish about the Swedish colony? How did they transmit and transform theirculture here?

“We ask the same questions of the Finns, Dutch, English, Africans and native and immigrant American Indians,” she adds. “Colonial borderlands like New Castle are so complex. The archaeological remains are sometimes the only resources we have to answer those questions.”

At its completion in 1804, the George Read House, on the Strand in New Castle, was Delaware’s largest domicile, with 22 rooms. More than 70,000 artifacts have been unearthed from its grounds.

At its completion in 1804, the George Read House, on the Strand in New Castle, was Delaware’s largest domicile, with 22 rooms. More than 70,000 artifacts have been unearthed from its grounds.

The “Survey of Newcastle,” by Benjamin Latrobe and his assistants in 1804–1805, provides a detailed record of the town. A fire in 1824 destroyed many of the houses.

The “Survey of Newcastle,” by Benjamin Latrobe and his assistants in 1804–1805, provides a detailed record of the town. A fire in 1824 destroyed many of the houses.

Lu Ann De Cunzo puts together the shards of a glass wine bottle excavated from the grounds of the Read House.

Lu Ann De Cunzo puts together the shards of a glass wine bottle excavated from the grounds of the Read House.

UD students spent each Friday of their spring semester last year surveying, mapping and excavating the Read House’s four-acre riverfront lot.

UD students spent each Friday of their spring semester last year surveying, mapping and excavating the Read House’s four-acre riverfront lot.

UD students learn how to use ground-penetrating radar to “see” below the ground surface.

UD students learn how to use ground-penetrating radar to “see” below the ground surface.

UD’s Lu Ann De Cunzo (right) and Michele Anstine from the Delaware Historical Society are bringing New Castle’s colonial past to light through the objects excavated from the grounds of the historic Read House.

UD’s Lu Ann De Cunzo (right) and Michele Anstine from the Delaware Historical Society are bringing New Castle’s colonial past to light through the objects excavated from the grounds of the historic Read House.