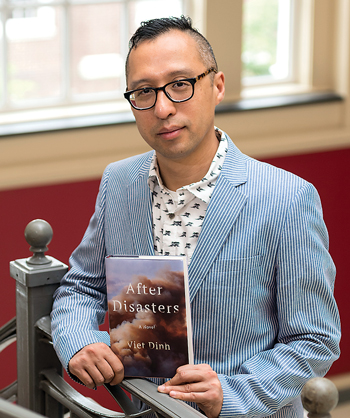

5 minutes with Viet Dinh

OUR FACULTY | UD’s assistant professor of English discusses his novel, After Disasters, which recounts the stories of four disaster assistance workers who travel to India to help after a major earthquake. Earlier this year, the 42-year-old’s book was selected from more than 500 works of fiction as one of five finalists for the 2017 PEN/Faulkner Award, the largest peer-reviewed literary prize in the country.

What types of stories are you drawn to?

Ones in which people are forced to reckon with who they are deep down inside. A lot of times, this comes in the form of radical change—a disaster, if you will, whether large in scope, like a natural disaster, or on a more intimate scale, like a divorce. I’m also a sucker for horror movies, and write haiku horror movie reviews in Twitter for fun (@vietpdinh). I think fear is a real and primal emotion. Horror movies, when they’re done well, they shine a light on society. They’re almost pure metaphor.

What interested you in the topic of disaster relief?

The people, definitely. I wanted to explore the personalities of those who choose that line of work. I think we have a tendency to imagine aid workers as altruistic saints, whereas the truth is that they’re human, with human foibles and failings. I just find that when people are pushed to react to a radical change, that’s when they reveal their true selves.

What was the reporting process like? Did you connect with UD’s Disaster Research Center for any of the research?

As a matter of fact, when I started developing the idea of my novel, I turned to the Disaster Research Center for some of my initial research, and I also relied on Morris Library for some of my materials. I took a research trip to India in 2008. For a long time, the place, the idea, only resides in your head. When I went to India, the novel became more concrete. It made everything more real, and that helped the writing process.

Readers and critics have commended the book’s exploration of male sexuality through the main characters. How has the reaction aligned with your intentions?

Oh, that was definitely one of my intentions. Along with the earthquake, I wanted my characters to wrestle with disasters of a more personal nature: failed or failing relationships, the inability to connect and the grand mysteries of attraction and love.

What do you hope readers take away from your book?

To paraphrase Roger Ebert, I think that fiction is an empathy machine. If nothing else, I’d like readers to step into the lives of these people, live with them for a little bit as they work, then return to their own lives a little wiser, sadder and more in touch with humanity.

As a professor for the past 10 years, how does teaching inform your writing, and writing inform your teaching?

Even though writers ply their craft in isolation, one of the things that keep us going is the sense of community, and that’s one of the things that I both bring to the classroom and take away from it. Writing is as much a way of teaching people as being a professor is.

What’s next?

I’m finishing up a collection of short stories that revolve around the aforementioned love of mine: horror movies. After that, I’ll start work on a new novel that takes place in an even more exotic locale: post-World War I rural Wisconsin.