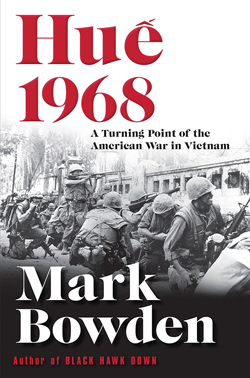

Hue 1968

OUR FACULTY | “The Battle of Hue would be the bloodiest of the Vietnam War, and a turning point, not just in that conflict, but in American history. When it was over, debate concerning the war in the United States was never again about winning, only about how to leave. And never again would Americans fully trust their leaders.”

So begins Hue 1968, the most ambitious work yet by UD Writer in Residence and veteran journalist Mark Bowden, whose latest book explores how a brutal battle for an ancient city would change history. Framing the story with voices and perspectives from all sides, it offers an anecdotally rich account of the war’s biggest and bloodiest battle. And much like Bowden’s earlier military narrative Black Hawk Down, his newest bestseller seems destined for the screen—Oscar-nominated filmmakers Michael Mann and Michael De Luca have already acquired the rights to adapt it as a miniseries for FX.

Here is an excerpt from Hue 1968:

Palace Soldiers

As the last light of the old year faded, Le Huu Tong was marching toward darkness on the outskirts of Hue dressed in a spanking new uniform. His NVA regiment, the Sixth, a body of nearly two thousand men, had camped at a mountain base for the last two days. They had taken a long and harrowing road there, and the days had provided welcome rest, good food, the new uniforms, and, finally, a clear mission. Like infantry everywhere, he lived a life of strenuous routine and uncertainty, never quite knowing what the big picture was, where exactly he was going, or why. Tong had always felt a sense of purpose, but missions had been harder to come by. He had been in the army for five years. He was twenty-two, a native of Ha Nam, a province immediately south of Hanoi. He had not been home in years.

The Sixth had been ordered south in July 1967 after fighting for some months in Laos. Tong’s battalion, more than four hundred men, was the last to begin walking. American air strikes had destroyed most roads and bridges, so they made the trek on foot along forest and mountain trails, moving mostly at night without flashlights. Sometimes they were guided only by the fungi that glowed on tree branches, or men in the front would catch fireflies and hold them in their hands or crush them on their caps so they could be seen. In the rainy season small streams would rise before them suddenly, and become too violent to cross. Then the men who had already gone over would sit and wait, sometimes for days, until the waters ebbed and the rest could join them. They walked for months this way, dragging themselves over mountains that often took a day or more to summit—the Nguyen Chi Thanh Mountain pass was more than three thousand feet high—carrying everything on their backs. Tong’s load weighed about eighty pounds. He was part of an antitank squad, and lugged a bazooka and ammo. Some carried more. Each soldier also carried a week’s worth of food, two sets of clothes, mosquito netting, a small blanket, and a bundled nylon hammock. They wore rubber sandals made from tires, which, when the path was muddy, would sometimes be sucked right off their feet. Soon into the march Tong had discarded his long pants. Leeches would attach themselves to his legs, and with the long pants, he would not realize it until the slimy creatures were fat with his blood. The men would roll rice balls and carry them in their pockets, eating them cold, sometimes for days at a time before they rested and could cook. Rest came when they reached occasional camps along the trail where there were poles in the ground from which they could string their hammocks. Sometimes traveling propaganda troupes of performers entertained them at these stops, performing plays and singing folk songs that illustrated the party’s ideals and goals. There were pretty girls in the troupes.

Tong’s battalion moved in segments. One would march ahead, and the others would wait, sometimes for weeks, before following. Avoiding encounters with superior-armed American soldiers on search-and-destroy missions was critical. One such clash had forced them to take a weeks-long detour into Laos. There were other hazards. At points along the trail American agents had placed listening devices. These would trigger air raids out of nowhere, usually at night, when C-130s dropped flares and blasted away with powerful cannons and machine guns. Jets loosed terrifying splashes of napalm. There were also mines, about the size of a man’s fist, which could blow off a man’s legs. Many of the men in Tong’s battalion were killed or wounded on the way. When they reached the Ben Hai River, which flowed along the demarcation line between North and South, the battalion was so depleted they set up camp and waited for reinforcement. It took them over four months of walking, with occasional stops like the one at the Ben Hai, before they reached Ba Long Province, rejoined the other battalions of the Sixth, and established a base camp to prepare for what would come next.

They were met at Ba Long by VC troops who welcomed them to their ranks. Tong officially became a member of the Front, trading the red star of the NVA, worn on his helmet, for one that was half red and half blue. Not long afterward they encountered helicopter-borne American forces, and engaged in a running battle with them for nearly a month before making it farther south. They had finally arrived in Quang Tri, just north of Hue, near the end of the year.

On the eve of Tet, Tong’s battalion assembled to receive its orders. The commanders of each unit read out the mission for that night. All were taking part in a grand offensive to liberate the city of Hue, which Tong had never seen. Most of the Sixth was going to attack the northern half of the city, the Citadel. Tong’s battalion would join elements of the Fifth, which was going south of the Huong River to take down an ARVN armored camp at the lower tip of the triangle, Tam Thai. They were read their formal orders at a large assembly. The opening words were: “Move forward to achieve final victory!” It called for combat by the army and population:

And in compliance with the attack order of the Presidium, Central Committee, South Vietnam Liberation Front, all cadres and combatants of all South Vietnam Liberation Armed Forces should move forward to carry out direct attacks on all the headquarters of the enemy, to disrupt the United States imperialists’ will for aggression and to smash the Puppet Government and Puppet Army, the lackeys of the United States, restore power to the people, completely liberate the fourteen million people of South Vietnam, and fulfill our revolutionary task of establishing democracy throughout the country. It will be the greatest battle ever fought throughout the history of our country. It will bring forth world-wide change but will also require many sacrifices. It will decide the fate and survival of our Fatherland and will shake the world and cause the most bitter failure to the imperialist ringleaders.

All of them raised their hands and pledged an oath: “All is for liberation of Hue; all is for liberation of South Vietnam.” Then they were served a holiday feast of dumplings and Tet cakes. They were given canteens filled with tea. The propaganda troupes entertained them. Then, to underscore the historic nature of their undertaking, they were issued new khaki uniforms, made in China: a broad-brimmed cap, a gabardine shirt, clean trousers, and ankle-high boots. Bright strips of torn red and blue cloth were pinned on the left sleeves to signify that they were part of the Front.

The new uniforms were meant to impress. City dwellers in the South had been fed lies about the VC and the NVA for years. They were portrayed as uncivilized, even animal-like. So the Front was going to do more than liberate Hue; it was also going to dazzle it. They were given lessons in polite behavior, memorizing twelve rules of conduct. They were to take nothing, to help tidy the streets, to repair broken utilities like sewers or wiring, in other words, to make themselves useful. They would present themselves to Hue as a clean and disciplined professional army. This was to be the last battle, and they were going to win it. They wanted to look and behave like winners. Many of these young soldiers had never owned a suit of clothes as fine as the ones they now wore. It filled them with pride and a sense of importance.

They were so certain of final success that they joyfully destroyed their camps. Living in the jungle was hard, and was at long last over. Le Kha Phieu, who years later would become the party’s general secretary, joined in as members of his unit urinated on their camp stove before leaving. They were never coming back.

Readers Write:

One of Hue 1968's central themes is the concept of "spizzerinctum," or the will to succeed. The Messenger invites readers to share their stories of grit and determination—sent to themessenger@udel.edu—for a chance to win a signed copy of the book.