Home of the Brave"

OUR FACULTY | In the sun-dappled shade of The Green, a quiet man walks alone, seeming to be part of this tranquil setting, yet somehow feeling apart from it all. Chipper, chatty students pass, never thinking to see him as the warrior he once was, never imagining how his memories can be so painful yet so uplifting.

They don't know what it takes—to endure 20-hour shifts gripped by life-or-death stress while flying at 40,000 feet; to see dear brothers and sisters fall and never rise; to wonder, in those reflective moments: Did I do all I could for them, for my country? When I had to engage in combat, was this an honorable thing? And why am I here, when so many never came home?

To the men and women trained in the drilled-tight procedures of the military, the breezy individuality in academia’s DNA can seem decidedly loose, too lacking in the steely personal bonds and solemn, regimented responsibilities that once defined their core.

Despite their indelible pride in serving, the details of those sometimes-dangerous overseas deployments go unspoken. In class and among classmates, UD’s veterans often struggle to relate, or to even feel a casual connection. Instead, many stick to their studies, work to support their young families, and soldier on.

But for the 500-plus student veterans of UD, there is an answer to their isolation, and one that is typically military-minded. They can face this challenge as they always have: together, as airmen, Marines, soldiers, sailors. Because once these folks start fighting, winning is all they know.

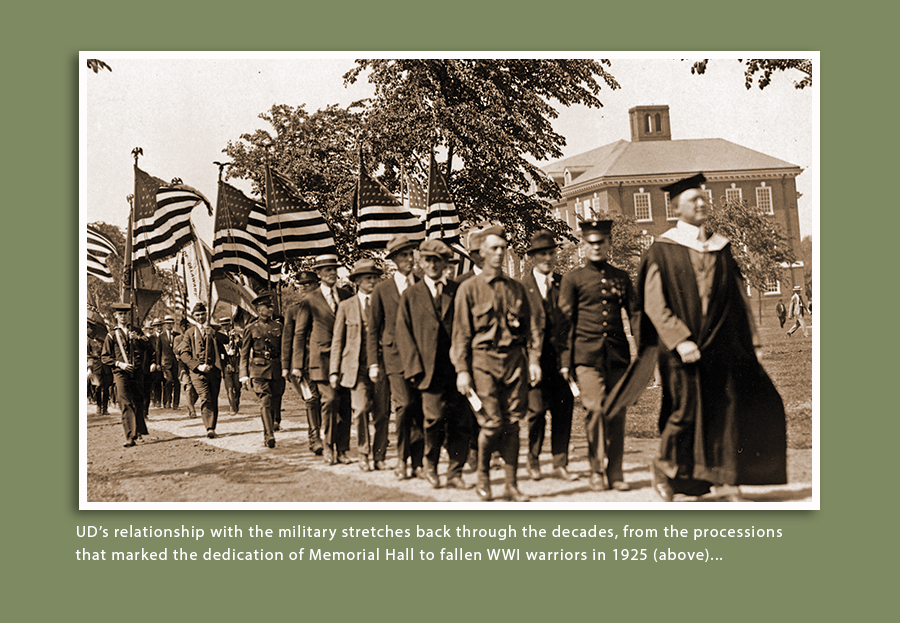

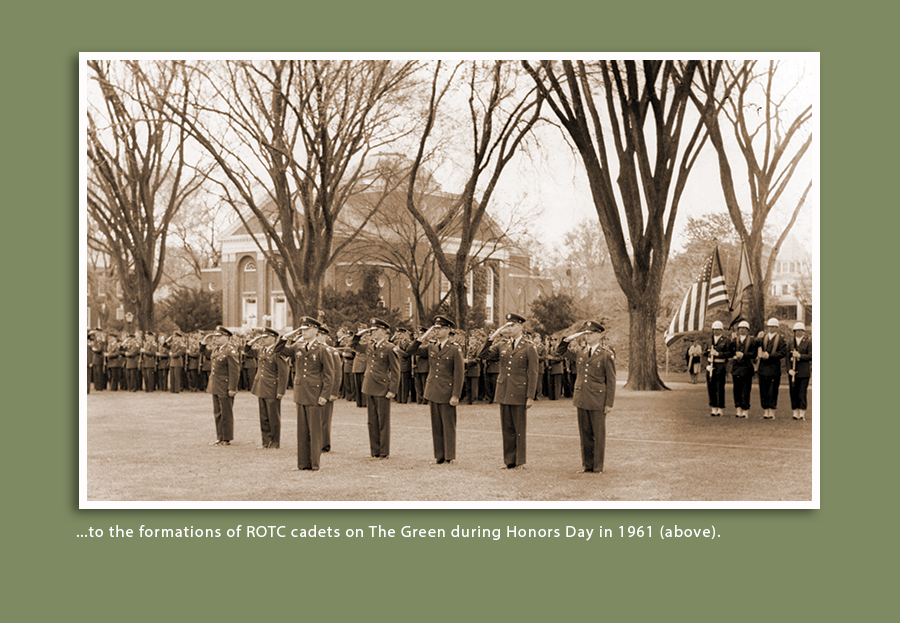

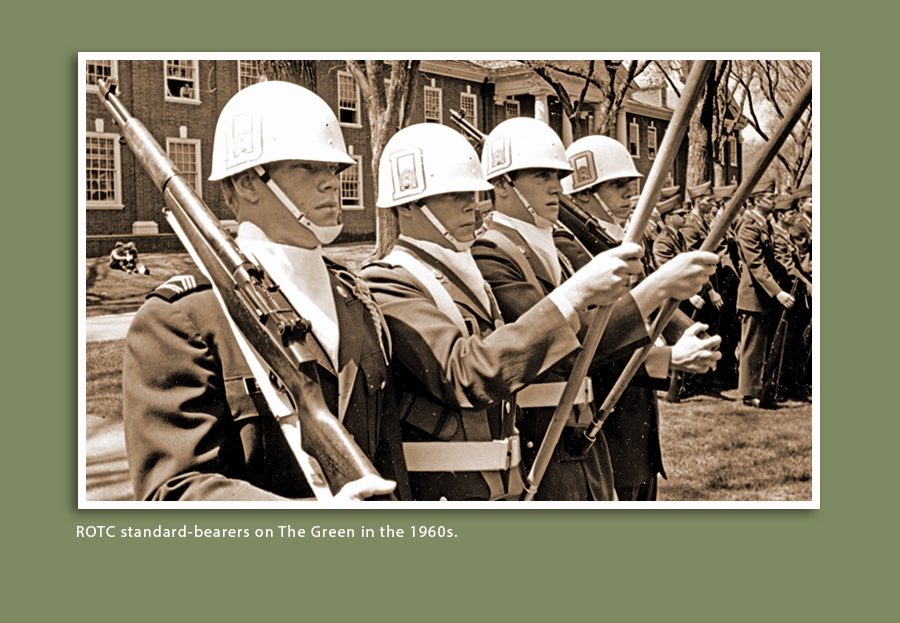

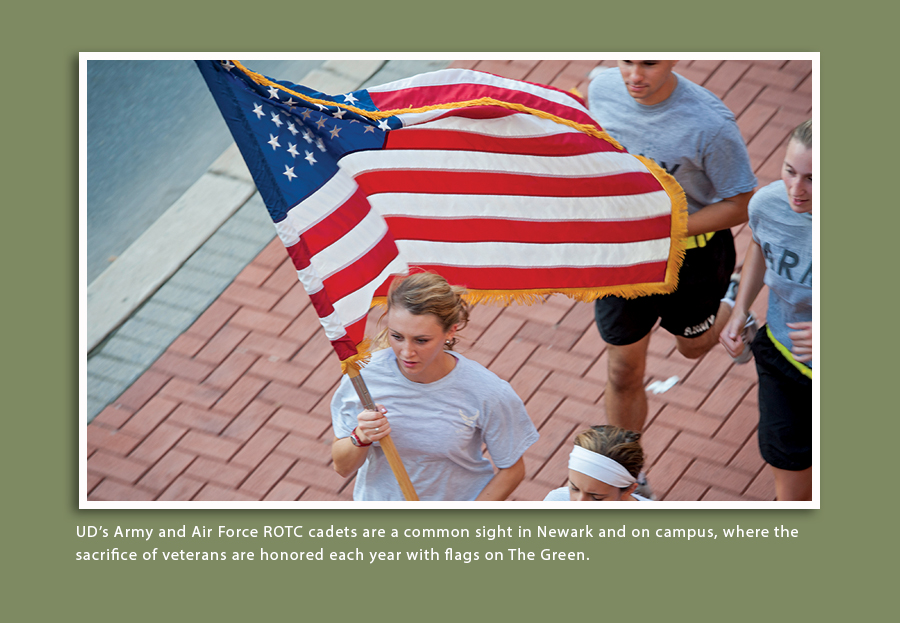

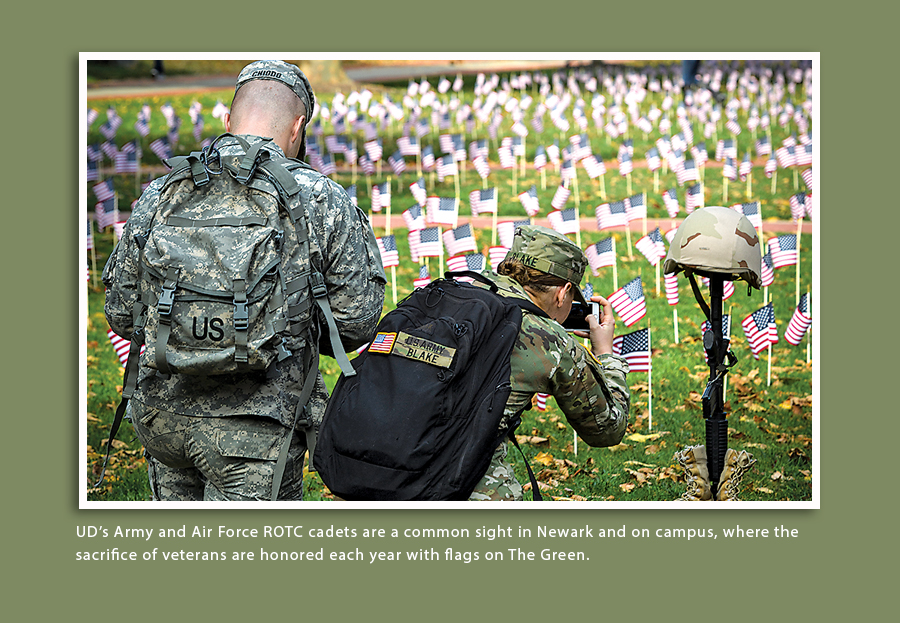

UD’s relationship with the military stretches back through the decades, from the processions that marked the dedication of Memorial Hall to fallen WWI warriors in 1925 (above left), to the formations of ROTC cadets on The Green during Honors Day in 1961 (above right).

THE MISSION BEGINS

The resurgence in veteran activism at UD got under way in 2009, with a chance meeting in class between two veterans seeking an understanding ear. Their friendship would eventually lead to the formation of a revamped student-veteran group, Blue Hen Veterans, that since 2013 has turned UD’s veterans outreach program into one of the nation’s best, according to Victory Media.

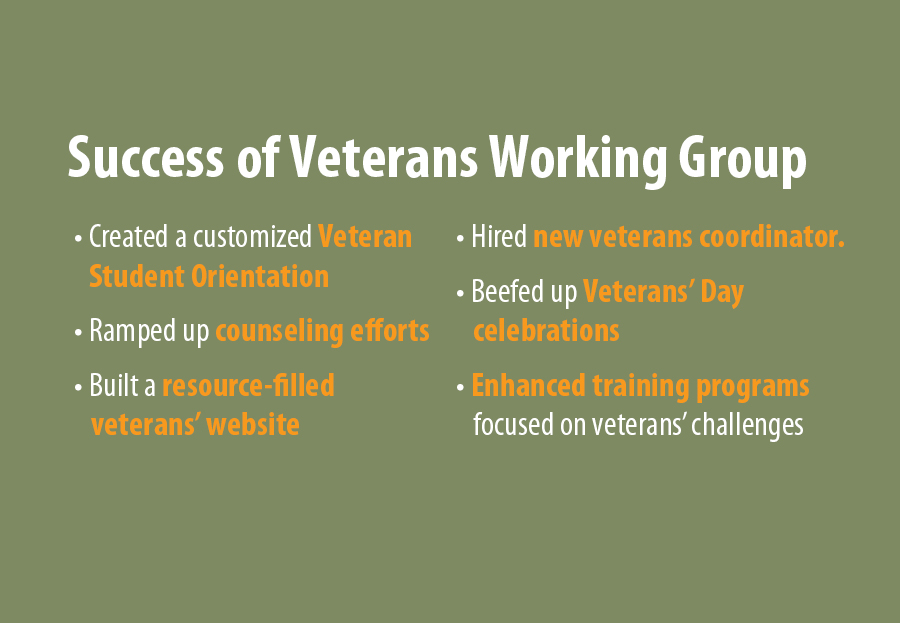

The list of their accomplishments over the past four years astounds even the UD administrators who helped make it happen. First, the students and their advisor, staffer Paul Pusecker, enlisted faculty and staff to seek solutions together. Soon, that effort would lead to the establishment of the Veterans Working Group, overseen by Dean of Students José-Luis Riera. Since then, the working group has created a customized Veteran Student Orientation; ramped up counseling efforts; and built a resource-filled veterans’ website. A new veterans coordinator was hired, Veterans’ Day celebrations were beefed up and training programs focused on veterans’ challenges were enhanced.

“You could not have two organizations that are more polar opposites than the university and the military,” Riera says. “That’s what makes recent progress so impressive—it really has been a partnership and a collaboration between students and administrators. UD is now focused on giving veterans a sense of comfort and belonging, and also finding ways to turn their experiences and skills into classroom assets.”

Today, the core student group is about 50 strong and beginning to build partnerships with alumni veterans, the Delaware National Guard and even UD’s ROTC cadets. Members are keenly focused on finding more ways to connect with students, engage with other campus programs, and enlist alumni veterans to serve as mentors. The students who had been part of the campaign are now graduating into the workplace as highly skilled, highly sought assets.

In those early days, however, the veterans had only themselves to rely on. But heavy lifting was no chore for these men and women who once excelled as combat medics, elite infantrymen, intelligence specialists and logistics officers.

“We decided that we were going to make something worthwhile,” says Jennifer Barnes, HS15M, a former Army maintenance and logistics officer. “These vets needed people to talk to who could understand what they were going through.”

Together, they felt hope rise again. Together, the old military sense of camaraderie started to re-emerge. “It was that sense of being part of something bigger than yourself again,” says Jeremy Schladweiler, BE11, a veteran of more than 50 combat medevac missions as a Navy corpsman/medic.

THE LONG ROAD

The initial challenge they faced was formidable. UD’s veteran outreach efforts then were meager. University support in coping with the sometimes-maddening post-9/11 G.I. benefits process—which since its inception in 2008 has helped pay for veterans’ education and indirectly support their families—was hit-or-miss. Left in the hands of one besieged staffer, G.I. benefit payments to students even fell behind at one point because of a post-retirement confusion.

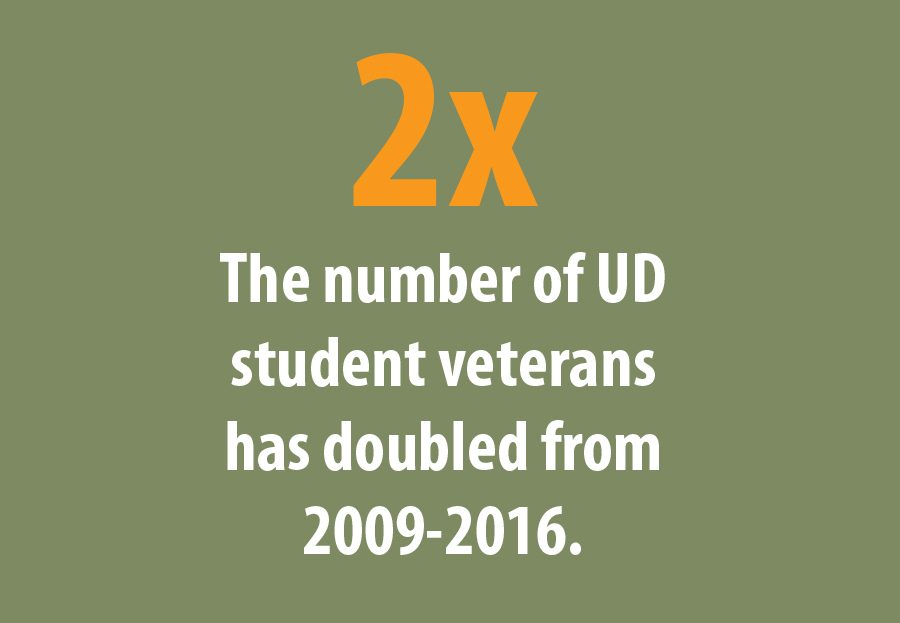

The problems stemmed, in part, from the steady post-9/11 increase in UD student veterans, whose numbers have doubled from 2009-2016. Today, the University educates roughly 500 veterans and their dependents each semester. But back when the numbers were lower, so, too, were the resources.

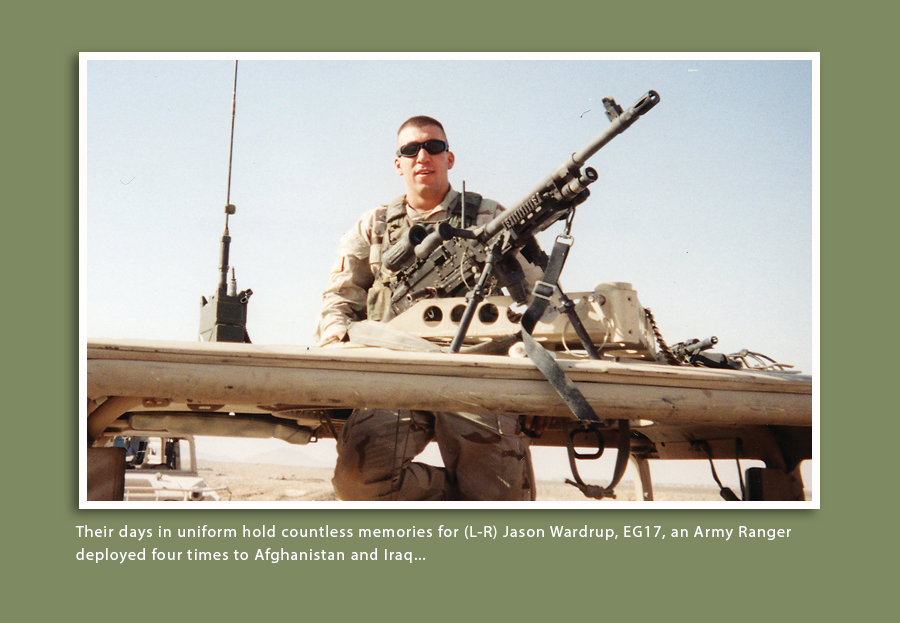

“You could also sense some frustration that there wasn’t a mechanism to identify veterans on campus,” says Jason Wardrup, EG17, an elite Army Ranger who was deployed four times to Afghanistan and Iraq, served 18 months in a combat zone, and was wounded once by shrapnel. “We felt that was something that was needed—those peer-to-peer relationships.”

The campaign for more services is only the most recent chapter in a long history of soaring-then-sinking support for the military on UD’s campus. Required by the federal government to include military science courses after the Civil War, the University and its students have warmly embraced the military side of academics at times—building monuments to WWI sacrifice like Memorial Hall, bolstering ROTC programs, opening its doors as wide as it could for returning WWII vets, conducting research for the defense of the nation, and most recently embarking on a partnership with the Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Wilmington.

Inevitably, it also would provide a steady stream of young men and women to serve in conflicts ranging all the way from the Mexican War until today, leading to a growing roster of fallen alumni.

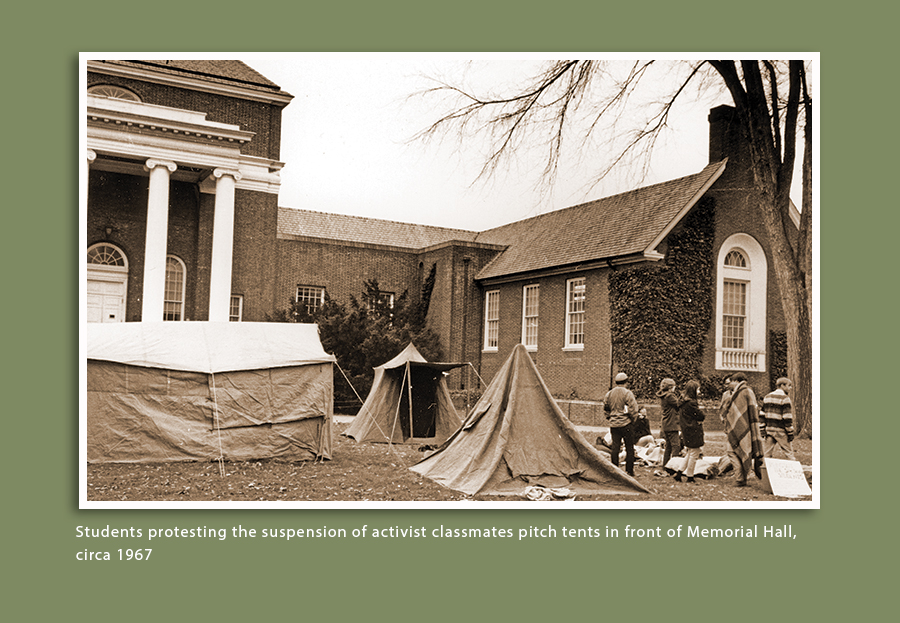

At the same time, military-oriented elements of campus life have also inspired outrage and contention. Protests against then-mandatory ROTC courses flared in 1926 and again in the Vietnam war era—the University president’s office was even firebombed by anti-war activists in 1972. The University struggled to cope with the influx of veterans after WWII, establishing “dorms” as far away as Elkton, Md., and housing veterans in fraternity houses when space ran out with vet enrollment at 63 percent and overall enrollment up 400 percent.

A PRESSING NEED

Today’s veterans say that once they managed to enlist influential administrative allies—such as fellow veterans Provost Domenico Grasso and Vice President for Enrollment Management Chris Lucier—the campaign’s momentum soared. It also helped that, unlike the later days of the Vietnam war, they had public sentiment on their side, as well as statistics that plainly showed a need.

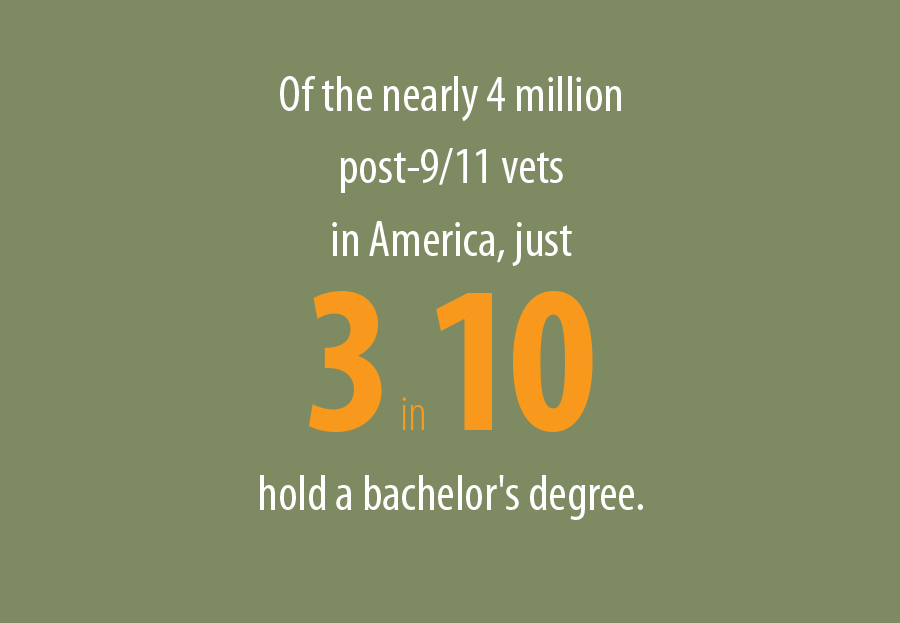

Of the nearly 4 million post-9/11 vets in America, just three in 10 hold a bachelor’s degree or higher, according to the Veterans Administration. At the same time, younger returning vets are facing higher rates of poverty, homelessness and unemployment, according to the National Institutes of Health.

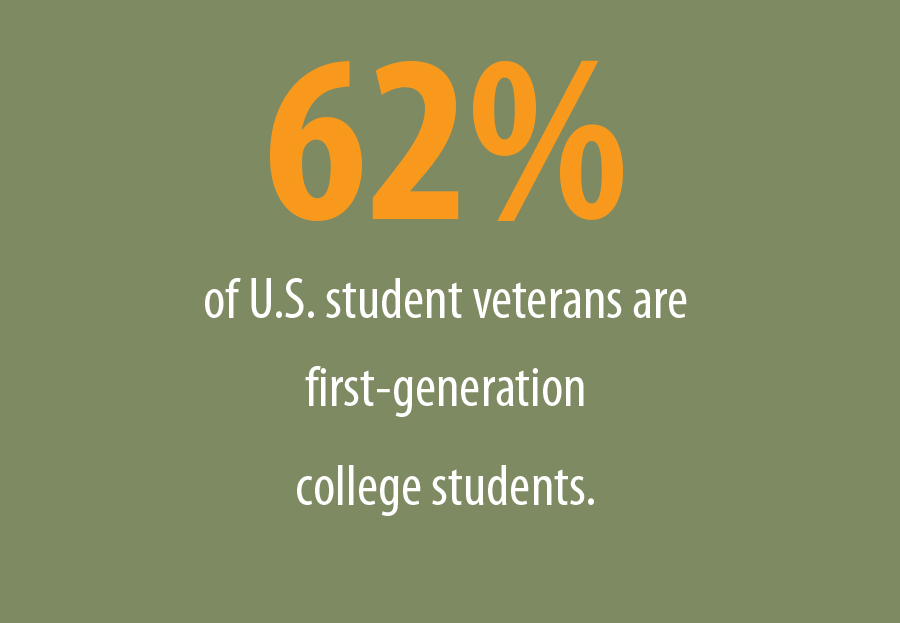

And for the veterans who do pursue college, those challenges are heightened. Many have families with children and must juggle schoolwork with employment. Nationally, more than 60 percent using G.I. benefits are the first generation in their families to attend college. Studies also have found that student veterans in the U.S. are more at risk of low academic achievement and dropping out.

“Coming from military life to college life is a culture shock. You’ve been around the world, seen a lot of things, and you sometimes can’t relate to the average 18-year-old on campus,” says Brooks Raup, who came on board as UD’s student veteran services coordinator in December 2016.

Former Army logistics officer Barnes adds: “In a military community you have routine. There is a lot of structure, you know who to turn to when you have questions. On campus, it can feel a little disorienting.”

For Darrell Wisseman, AS16, a Marine intelligence specialist who once sailed in search of modern-day pirates, deeply instilled instincts were still engaged as he strolled the peaceful campus. “You’re just trained to be situationally aware and assess your environment. You’re hyper alert, and that’s something you don’t turn off.”

For former Army ordnance supply specialist Steve McGuire, EOE17, even walking to class could trigger the anxieties of duty in Bosnia, where the months were saturated with the smell of diesel vehicles waiting for loads of ammunition. “One day a truck passed as I was crossing College Avenue. I smelled it and said to myself, ‘Nope,’ turned around, went back to my car and drove to the VA Hospital.”

A few veterans—national estimates range from 11-20 percent—return with some degree of post-traumatic stress disorder, raising the risk of substance abuse and suicide.

“Some are working full time to put food on the table for their families. Some are disabled. And some just don’t want to speak,” says Mark Footerman, HS17, former president of the Blue Hen Veterans student group.

Many other veterans, while not suffering acutely from war’s stresses, still contend with occasional dark moments and troubled thoughts—something veterans say has been overemphasized to the point of stereotyping.

So even as they help veterans with real mental health issues find support, they also struggle to dispel the misconceptions of their young classmates. “It’s stigmatized, in that sense,” says Ranger veteran Wardrup, 36, who’s considering a run for public office since graduating with a bachelor’s degree in energy and environmental policy. “And that’s something we wanted to push back on, a lot.”

Those veterans who do hold darker memories say it’s something that can be eased with time and talk. But at the same time, in an oddly conflicted way, those haunting memories often are linked to something they would never want to lose—a deep and abiding love for their fellow soldiers, solidified through shared suffering and unified purpose.

That’s the way it was for Jeremy “Doc” Schladweiler, BE11, a cheerful and easygoing 40-year-old former Navy corpsman/medic who was deployed overseas when 9/11 struck, and who would fly 50 combat medevac missions. Often, as the helicopter crewman in charge of assessing casualties on the battlefield, he found himself making wrenching decisions about which wounded men were allowed aboard for the trip home.

“That’s one thing the military doesn’t train you for,” says Schladweiler, now a compliance manager in financial services. “I kept thinking: ‘How many people could I have saved?’”

“DID YOU SHOOT ANYONE?”

Long taught to suck it up for the good of the unit, some vets are disinclined to talk about their experiences or seek counseling. “It’s veterans’ nature not to seek help,” says Brandon Bristor, AS16, a one-time Navy policeman. “We’re really trained to put emotions and feelings aside, pick yourself up by your bootstraps, and move forward.”

After serving 18 months in the Middle East, Bristor had just 21 days to readjust before he found himself sitting in a UD classroom. Opening up about where had just been, he was quickly met by blank stares and uncomfortable tension.

“So, did you get to shoot anyone?” one student asked, clearly hoping for some vicarious horror.

The student would leave disappointed, and Bristor would realize then how quickly college could become a minefield of misconceptions.

“It’s a culture shock, really,” said 33-year-old Air Force veteran Michael Ivey, EG17, of his first days on campus. “You just say your age, and they say, ‘Oh my God, really, you’re that old?’ It’s like I’m not fitting in. And you want to fit in."

Thanks to UD’s support, vets say the challenge of belonging is less formidable today. Veterans say the changing campus climate has made it easier to connect with fellow students—bolstered by public awareness efforts such as annual Veterans Day celebrations, which Raup and the students aim to expand into a week-long series of events this year.

“I was always trying to find that sense of purpose like I had in the Army,” Wardrup says. “I thought I lost it, but it was here at UD all the time. We just had to find it again.”

Veterans have also made lasting connections with Student Government Association, and now serve as mentors to ROTC students. They are committed to creating an organization where all students—not just veterans—can have a role and a voice.

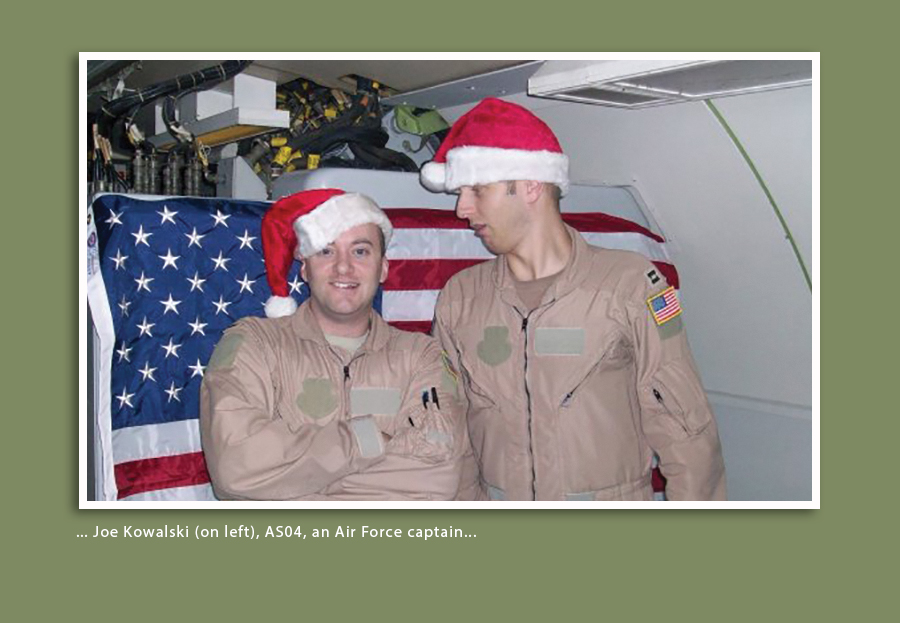

“The first year, I just tried to fly under the radar,” says Joe Kowalski, a 37-year-old former Air Force captain who once guided battles from his radar screen aboard an airborne command center, and is now preparing to pursue his master’s in environmental engineering. “I didn’t raise my hand much. But I’ve gotten a lot more social.”

VET-TO-VET

While campus culture feels more welcoming than it did, student veterans say the impulse to find and talk with other vets remains strong. Raup has made a veterans’ lounge a priority—the will is there, he says, but finding a space remains a challenge. “We have found the quicker we can connect a vet to another vet, the chances of their social and academic success will go up,” adds Riera.

It’s an empathetic bond that exists even between vets who have never met before, instilled by the unbending trust necessary for military ordeals. In combat zones, where there can be no errors, dependability is key.

“It’s like we speak the same language,” says Barnes, who is now pursuing her PhD in biomechanics and movement science in order to help disabled vets. “We understand each other, and we know what to expect from each other. There’s a certain level of comfort that comes with that.”

At the University, Riera aims to ramp up a training program to help staff and faculty become more aware of veterans’ issues and available services, and wants to also enlist faculty and staff as veteran mentors. At the same time, alumnus Ken Jones, BE80, has been working to pull graduates in to help, establishing the Blue Hen Veterans and Friends nonprofit and assisting the students with funding.

“Our main objective is to connect student veterans with alumni and friends who can provide their support when needed, especially with employment and mentoring,” says Jones, a retired helicopter pilot in the Delaware Army National Guard.

Meanwhile, the Blue Hen Veterans group is finding more allies eager to contribute to the overall mission. Connections are in place with a nonprofit called Reviresco, conceived by UD undergraduates to show civilians how they can help vets, and partnerships are growing with the Delaware National Guard and Delaware Commission of Veterans Affairs.

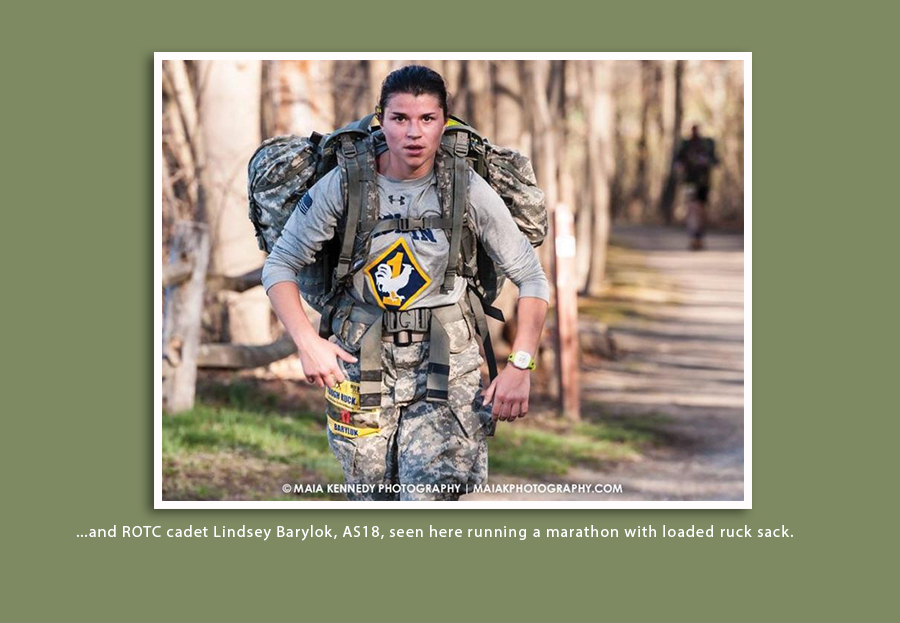

On campus, UD’s Army and Air Force ROTC students are actively supporting the veterans’ cause, and receiving support in turn. “We’re lucky to have these people here—they are a great resource,” says Lindsey Baryluk, AS18, an ROTC cadet and current president of Blue Hen Veterans. “They have mentored me, showed me the ropes. You can see they are very disciplined people. Just the fact that they’re doing this says a lot about their character, and a lot about this school.”

And, as UD offers more substantial help, it stands to gain in reputation. The military-friendly school designation, awarded by the militaryfriendly.com website, focused partly on UD’s retention rate and graduation rate for veterans, and could prove to broaden UD’s appeal among vets, helping boost enrollment at a time when competition for new students is keen and heightening academic richness as veterans’ experiences and expertise make their way into classes.

“These students are making UD a better place, and UD is helping them fulfill their dreams of changing the world,” Riera says. “This is a story about an incredibly collaborative spirit from a lot of people at the University of Delaware who worked hard to make this happen.”

Article by Eric Ruth