Data analysis shows massive ice island

ON THE GREEN | In early August, when an enormous piece of a glacier broke away in the Arctic, the event drew the world’s attention—thanks to the work of a UD researcher who analyzed satellite data showing the occurrence.

Andreas Muenchow, associate professor of physical ocean science and engineering in the College of Earth, Ocean, and Environment, was the scientist who reported that the “ice island” had calved from Greenland’s Petermann Glacier. The last time the Arctic lost such a large chunk of ice was in 1962.

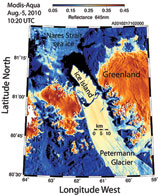

“In the early morning hours of Aug. 5, 2010, an ice island four times the size of Manhattan was born in northern Greenland,” Muenchow said at the time. His research in Nares Strait, between Greenland and Canada, is supported by the National Science Foundation (NSF).

Satellite imagery of this remote area, about 620 miles [1,000 km] south of the North Pole, reveals that Petermann Glacier lost about one-quarter of its 43-mile-long [70 km] floating ice-shelf.

Trudy Wohlleben of the Canadian Ice Service discovered the ice island within hours after NASA’s MODIS-Aqua satellite took the data on Aug. 5, Muenchow said. These raw data were downloaded, processed and analyzed at the University in near real-time as part of Muenchow’s NSF research.

Petermann Glacier, the parent of the new ice island, is one of the two largest remaining glaciers in Greenland that terminate in floating shelves. The glacier connects the great Greenland ice sheet directly with the ocean.

The new ice island has an area of at least 100 square miles and a thickness up to half the height of the Empire State Building.

“The freshwater stored in this ice island could keep the Delaware or Hudson rivers flowing for more than two years,” Muenchow says. “It could also keep all U.S. public tap water flowing for 120 days.”

The announcement of the discovery brought widespread media attention not only to the Arctic but also to the University and to Muenchow’s research. In the days after Aug. 5, he was quoted in a host of newspaper articles and broadcasts. Reports were carried on CNN, BBC, National Public Radio and the Australian Broadcasting Corporation, and published by Bloomberg, Associated Press, Agence France-Presse, Xinhua, UPI, National Geographic, Times of London, USA Today, New Republic, Toronto Globe and Mail, Montreal Gazette, The Guardian (United Kingdom), Times of India, AOL News and The News York Times Green blog.

In September, the ice island entered Nares Strait, a deep waterway between northern Greenland and Canada where, since 2003, a UD ocean and ice observing array has been maintained by Muenchow with collaborators in Oregon (Prof. Kelly Falkner), British Columbia (Prof. Humfrey Melling) and England (Prof. Helen Johnson). There, the ice island repeatedly struck a small rocky land mass called Joe Island and eventually split in two.

“The forces of the ocean currents and the winds wiggling it on and off the island were too much,” Muenchow said in a Sept. 10 CNN interview explaining the ice island’s split.

He told CNN that the incident was the biggest break-off in 140 years and that his research team had consulted the earliest known reports about the glacier.

“We went back to 1876 to find all glacier positions that have ever been reported,” he said. “From this analysis, we found that this indeed was the largest event that has been observed at Petermann.”

In the same interview, Muenchow predicted that the main pieces of the ice island will be found off the eastern Canadian province of Newfoundland and Labrador in two to three years.