ALUMNI | Every day, tucked into a corner of the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of Natural History, thousands of insects and butterflies are eating and making messes, reproducing and living and dying. And Nathan Erwin, AG ’81, is responsible for them all.

As manager of the museum’s Insect Zoo and Butterfly Pavilion, which host more than a million visitors a year, Erwin is interviewed by the media on all things insect-related, oversees the upkeep of two large exhibits and, with several other employees, brainstorms ways to exceed visitors’ expectations.

“We’re the entomological ambassadors of the museum,” Erwin says. Despite the other duties, Erwin’s main task is simply this: to tell the stories of insects and butterflies—and what they mean to our world.

But long before he was on network TV, regaling David Letterman with stories about cicada emergences, and traveling to Latin America to scout butterflies for museum exhibits, Erwin was a young boy fascinated by nature.

“I got hold of a butterfly net when I was about 10 or 11,” he says, “and I used it to catch frogs and pollywogs.” When he went to nature camp, Erwin lugged his Kodak Instamatic camera to photograph the bugs he studied. “The insect photos were horrible, but it did not deter me,” he says. When camp counselors told him he could turn his fascination with creepy crawlers into a full-blown career, Erwin never looked back.

During his senior year of high school, Erwin stopped by UD’s College of Agriculture and Natural Resources building. Hoping to merely pick up a brochure about the entomology program, Erwin instead found himself on a tour with Dale Bray, then chairperson of the Department of Entomology and Applied Ecology. “I was so impressed with that that I said, ‘This is the place I have to go to school,’” Erwin says. He enrolled in 1977.

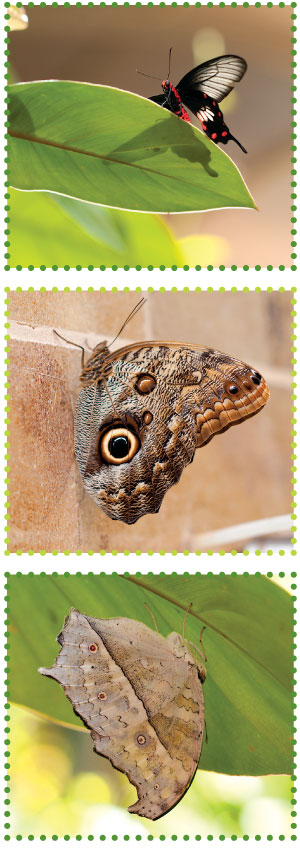

At the University, Erwin continued to follow his passion for bugs and butterflies. He took a course on insect photography with Richard Weber, a now-retired scientist in the entomology and wildlife ecology department. Finding he had a knack for capturing images of the tiny creatures, Erwin continued photographing insects after the course ended, using his shots to give presentations at nature centers.

“It’s one of the tools that has kept me going on as a lifelong learner,” he says. “I got a lot of experience speaking in front of people and telling the stories of insects and plants.”

Another career-launching experience came in the summer of 1980, when Erwin worked on a wood thrush research project with Roland Roth, now a professor emeritus of entomology and wildlife ecology. During the project, which examined wood thrush population dynamics, Erwin learned to band birds—a skill he used throughout his early career.

Roth remembers Erwin excelling at a time when few students had caught the entomology bug. “He was one of the top students academically,” Roth says. (In 1997, Erwin was formally recognized by the University with a Presidential Citation for Outstanding Achievement.)

After receiving his bachelor’s degree in entomology, Erwin leveraged his wildlife work into a position as a forest pest entomologist with the Maryland Department of Agriculture. He was soon tasked with the problem of gypsy moths, which exploded in population there in the early 1980s. Erwin conducted surveys and joined control programs to root out infestations. Eventually, he coordinated the statewide gypsy moth control program.

He moved on to the Rachel Carson Council, where he worked for four years on the book A Basic Guide to Pesticides. That experience, coupled with speaking engagements about gypsy moths, caught the attention of the Smithsonian, which had an opening in 1992 for an insect zoo specialist. Erwin got the job and began using exhibit development, education programs and websites to compose bug-filled narratives for museum visitors.

In the years since, his days have been filled with ever-changing tasks. In between exhibit upkeep and visitor outreach, he served stints as the media’s go-to cicada expert during the 2004 emergence and as a script consultant for the 3-D IMAX film Bugs!

He also traveled frequently, trekking to Latin America to find butterflies and insects for exhibits. But after a brainstorming session with colleagues, Erwin encouraged butterfly farmers in Costa Rica to grow other insects—and to ship them to his museum and others, minimizing carbon footprints and bringing jobs to the region.

For Erwin, his work is much bigger than the tiny insects he cares for. “Without them, all the other animals we think of, including us, just wouldn’t be able to exist,” he says. “It really is important to understand the crucial role they play in ecosystems around the world.”

Article by Christina Hernandez, AS ’06