When researchers at UD need standard test tubes for their lab, they purchase them in bulk from a catalog.

When they need a one-of-a-kind glass instrument or a special modification to a piece of apparatus, or when they break an expensive item, they turn to the University’s Scientific Glassblowing Shop, where—odds are—Doug Nixon can help them.

“Anybody on campus in a research program knows I’m here,” says Nixon, a glass technologist who has operated the shop for 20 of its 40 years. “Most of the pieces I fabricate are fairly complex or specialized. I get 10-minute jobs and two-day jobs, and not many of them are the same.”

The glass shop is housed in the Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, but Nixon does work for any faculty or student researcher who needs his services, including those in geology, physics, marine science, chemical engineering and animal science. Unlike an ornamental glassblower, who starts out with a pot of molten glass, Nixon begins his creations with such raw materials as hollow tubes, solid rods or plate glass, shaping and assembling them to fashion a new device. Different types of glass have different properties, but Nixon says he most often uses Pyrex, which is especially useful in labs because it can be heated without shattering.

“Some of the jobs I do are very intricate,” he says. “When you’re putting pieces within pieces, you have to build from the inside out.”

Klaus Theopold, professor and chairperson of chemistry and biochemistry, calls Nixon “an artisan” whose skills are essential to the work that scientists do. “With 150 graduate students and many undergraduates doing research, Doug Nixon is one of our busiest staff members,” Theopold says. “The business of chemistry and biochemistry would simply be impossible without him.”

Chemistry doctoral student Wes Monillas agrees. “I couldn’t possibly perform any of my research if it wasn’t for Doug’s help,” he says. “I use a lot of very specialized glassware that would be prohibitively expensive or downright impossible to purchase.”

Nixon uses flames from a Carlisle bench burner to soften the pieces of glass with which he works, bending a straight tube so that it forms a right angle, for example, then opening a hole in the bottom of a flask where he can attach the tube and seal the opening. While he works, he often has a piece of rubber tubing in his mouth, gently puffing into the softened piece of glass to maintain its shape.

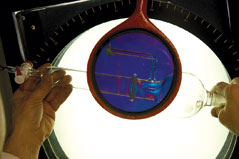

When a piece is completed, Nixon examines it with a polariscope, an instrument that uses polarized light to indicate invisible stress points where the glass is susceptible to cracking. Finished jobs are put into an annealing oven overnight, where they are reheated to about 600 degrees Celsius and then cooled very gradually to reduce the internal tension in the glass.

To Nixon, the very existence of the glass shop is proof of the University’s commitment to research.

“You can get a really good idea of the level of scientific research that goes on at a university by seeing whether or not they have their own glass-blower,” he says. “Only the larger, state-of-the-art programs have this capability in-house.”