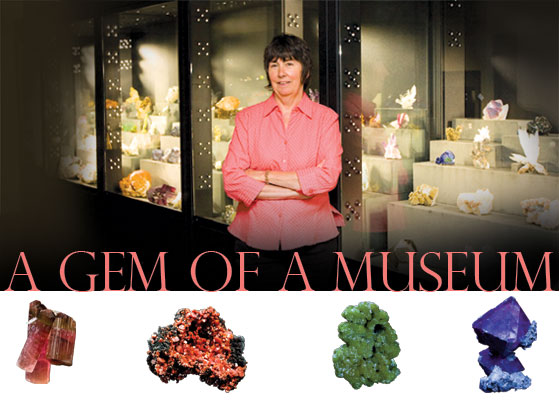

Visitors might go to a museum to view anything from paintings and sculpture to mummies and dinosaur skeletons, but a newly renovated exhibition space on campus offers a combination of art and science that sparkles with natural beauty.

The University’s Mineralogical Museum displays several hundred of its thousands of specimens of crystals and gemstones from around the world, along with visiting collections. It reopened this spring after undergoing a complete renovation and reinstallation, including the custom-made display cases with special fiber-optic lighting that allow visitors to view each item as it would appear in natural sunlight.

Located in Penny Hall on Academy Street, the museum provides educational resources for schools in the area and also attracts mineral enthusiasts. The new cases are lower to the ground than the former displays, making them more accessible for children and people with disabilities.

“A lot of school groups come to see the museum, and I especially like to talk to the children about collecting minerals,” says curator Sharon Fitzgerald, who earned master’s and doctoral degrees in geology from UD in 1973 and 1985 and a master’s in education in 1974. “It’s important to show them that these specimens all started with individuals who collected them for their own enjoyment—that minerals are found other places than in museums.”

Fitzgerald, who became curator in December 2007, previously worked as a gemologist and appraiser in Wilmington, Del. When she joined UD, she began researching similar museums to decide what form the renovations should take and then oversaw the entire process.

The museum’s specimens, which she estimates number close to 20,000, all had to be packed, moved into secure storage on campus and then returned to Penny Hall after the new cases were installed. The crystals, she notes, “are fragile, so the whole process took a lot of packing and a lot of time.”

The first of the changing collections to be displayed in the remodeled museum consists of amazingly complex copper specimens from the Keweenaw Peninsula in Michigan. “The case of Michigan coppers is interesting just because it’s neat to see the variation in one type of mineral,” Fitzgerald says. “These are all the same minerals from Michigan, and you can see how different they are from one to another.”

The other minerals on display come from exotic locations around world, with crystals from Mexico, Brazil and Morocco, as well as from sites closer to home, such as calcite crystals from York, Pa., and tourmaline from Elkton, Md. There also is a permanent display that includes minerals from the original gift from the estate of Irenée du Pont Sr., whose donation in 1964 helped originate the museum. It includes pyrite from Leadville, Colo., and one of the largest known topaz crystals from Texas.

Visiting collections will be displayed as well, the first of which belongs to David A. Byers, a longtime donor to the museum. In fact, Fitzgerald says, all the museum’s holdings come from the generosity of donors over the years, and she expects the collection to continue to grow.

Fitzgerald says she took the job as curator for one key reason: “This is a fine collection, an incredible collection. I really welcomed the opportunity to work with it.”

For more information, including hours of operation, visit www.udel.edu/museums.