A Window into a Different Time

Victorian Collection is the Largest Gift in UD Library’s History

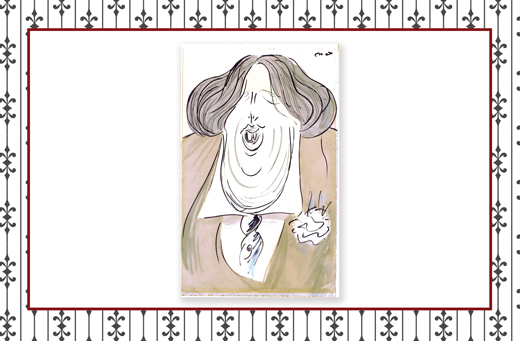

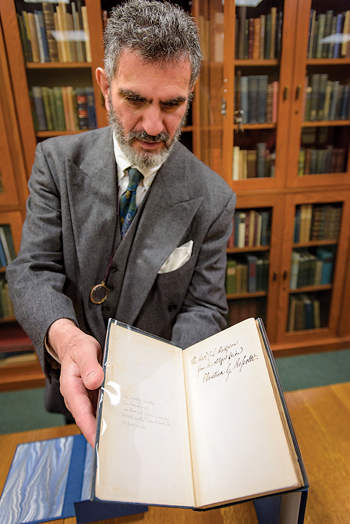

OUR UD | Mark Samuels Lasner has been called many things. A scholar. A dandy. A man who stepped out of a time machine. The foremost blind book collector in the world. Certainly, for a senior research fellow at Morris Library who regularly sports a three-piece suit, cane, fedora and monocle, all these characterizations are fitting. But if any description truly captures Samuels Lasner’s essence, it’s bibliophile—a lover of books. “With a book,” he says, “you’re literally holding history in your hand.”

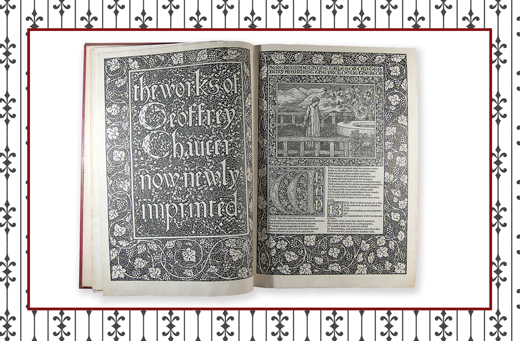

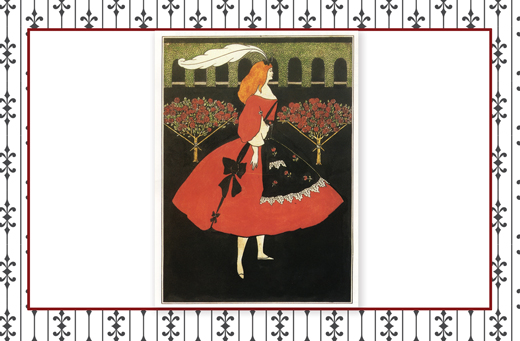

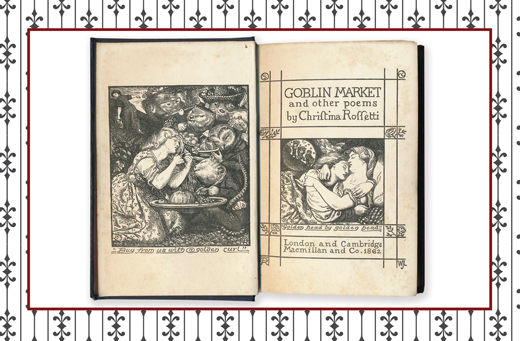

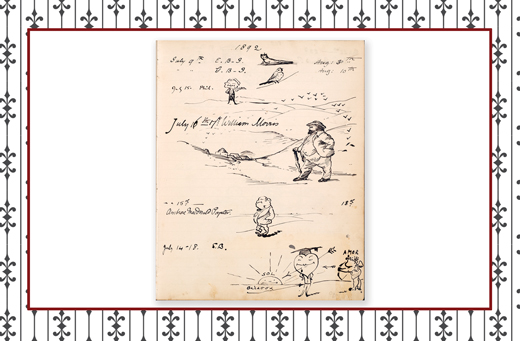

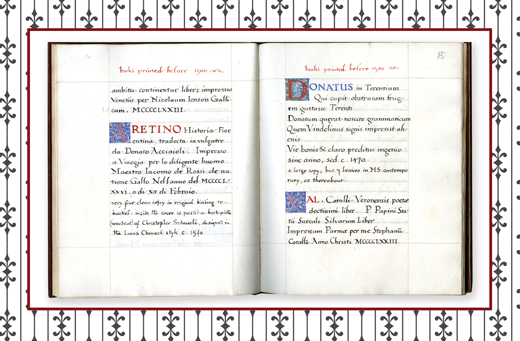

As one of the most celebrated private collectors in the country, Samuels Lasner has more than earned the title of book lover. And now, he can add another word to his identity: philanthropist. Last June, he donated his life’s work—a vast gathering of British literature and art of the period 1850 to1900—to the Library’s Special Collections. The collection is the largest and most valuable donation in the Library’s history. Appraised at more than $10 million, it contains some 9,500 books, letters, manuscripts, graphics and ephemera from a who’s who of Victorian cultural movers and shakers, including Oscar Wilde, George Eliot, Dante Gabriel and Christina Rossetti, William Morris, Max Beerbohm and Aubrey Beardsley.

Amassing the collection has taken Samuels Lasner to bookshops large and small, to auction houses and consignment shops, from New York to London, and involved relationships with museums and societies such as the National Gallery of Art and the Grolier Club, as well as with academics and other private collectors. The collection’s original appraiser, David J. Holmes, remarked that it would be “virtually impossible” to build something of its scope again.

And while some would be loath to part with something so irreplaceable, Samuels Lasner adopts a view as pragmatic as it is altruistic. “Collectors are the people who are left with the job of preserving and organizing our cultural heritage,” he says. “This gift is a way for the collection to live on.” Samuels Lasner hopes his gift will inspire others to recognize the importance of original materials and explore the worlds of knowledge they contain—to understand that a page is not merely a text, but a window into another time and place. In accepting the Mark Samuels Lasner Collection, the University has maade a commitment to a major library renovation, including the creation of a new Special Collections facility, which will have a transformative impact.

Samuels Lasner’s UD colleagues, who are among his biggest admirers, are confident that it will. L. Rebecca Johnson, head of the manuscripts and archives department at Morris Library and curator of the Joseph R. Biden, Jr. Senatorial Papers, believes the campus has been enriched both by the collection and by Samuels Lasner himself. “Mark is a true bibliophile,” she says. “He’s building bridges not only between people, but campus and other places, and between Delaware and the world.”

by Kevin Liedel, AS05, 07M

In His Own Words

On spending his childhood in a picturesque Queen Anne summer cottage:

“I grew up in a kind of turn-of-the-century palace—except with leaks and cracks. When the owner tore it down in 1961 and my grandparents had to move, it broke my heart. I think of collecting the late Victorians as my attempt to go back home.”

On being a teenager in mid-century America:

“I didn’t have a lot in common with my peers. But I was always fascinated by the 19th century. That’s where I felt I belonged. I often think that, like the Pre-Raphaelites who looked back with admiration at Medieval literature and Renaissance art, I’ve also looked back—just not so far.”

On fate:

“I’m a very firm believer in things eventually ending up in the right places. I’ve had too many odd coincidences happen. I know there’s something that causes them, though I don’t know what it is. I think collecting was thrust upon me.”

On collecting:

“You need a bit of ruthlessness. But to be really successful, you also have to be adept at forming friendships with booksellers, librarians, scholars and other collectors. If you are involved in a serious way, you will learn from these people, and that is most important.”

On being a book collector with limited eyesight:

“I’m legally blind and have been since birth. Books were wonderful, because I could bring them very close and read them and see them. I suspect this is also one of the reasons I like portraits. There is a long tradition of bibliophiles who have severe vision problems, and I think it’s because people who can’t make out things in general like to gather around them what they can see.”

On the collection itself:

“I’ve tried to capture in this collection the relationships and connections among hundreds of creative figures who lived between 1850 and 1900. There is one thing I’ve realized when it comes to the 19th century: Everyone knew everyone else, even if they didn’t necessarily know them very well.”

On UD being the right home for the collection:

“The University of Delaware is a great educational institution with a major research library. This collection can have a transformative effect on Morris Library, but more than that, it can be an inspiration to other potential donors and raise the University’s research profile. UD really is the perfect fit.”

On parting with the collection:

“I haven’t really parted with it. The collection and I are maintaining the same relationship. I’m still the caretaker and the enthusiast, and I’m always adding more to it.”