GMOs and the Future of the American Diet

OUR FACULTY | The gap between what scientists and the public believe about genetically modified organisms (GMOs) is now wider than it is on any other issue, according to a recent survey by the Pew Research Center and the American Association for the Advancement of Science. While 90 percent of scientists believe eating GMOs are safe, only 37 percent of Americans agree.

In his new book, Food Fight: GMOs and the Future of the American Diet, McKay Jenkins, UD’s Cornelius Tilghman Professor of English, gets to the bottom of this highly contested debate and finds the issues are far more complex than meet the eye.

An excerpt from Food Fight

(Edited for space)

Back in 1994, when I was pulling down four bucks an hour grading papers and teaching college students how to write, a friend told me about a can’t-lose investment scheme that was sure to lift me from my economic doldrums.

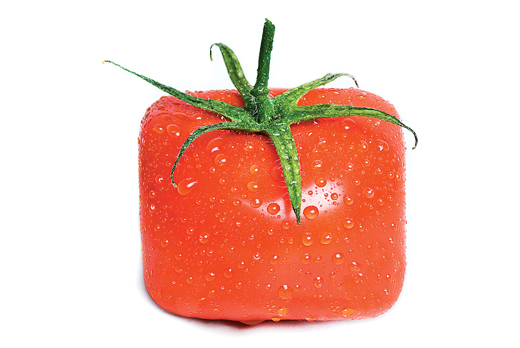

Forget about investing in Amazon.com, he said. Here’s what you need to get into: Square tomatoes.

They’re going to be great, he said breathlessly. They’ve had their genes altered by scientists! They stay ripe longer, and soften more slowly, and because they’re square, they can be stacked for shipping, which will bring transportation costs way down. It’s like the laboratory has taken nature and made it better!

The company that makes them will make a fortune, my friend said. And so will we! There was much truth to what my friend told me, and a good bit of misinformation as well. The product in question turned out to be the Flavr Savr tomato, a newfangled plant designed by a biotech company called Calgene. The Flavr Savr had indeed been designed not for exquisite taste, or enhanced nutrition, but to plug into an industrial food system already rapidly replacing traditional farming practices. Forget small farmers selling their fruit to their neighbors; this was big business. That year, 4 billion dollars’ worth of industrial tomatoes were being picked (and shipped) while still hard and green, then reddened with ethylene gas before hitting the supermarket shelves like crates of billiard balls. The genetically altered Flavr Savr, by contrast, was designed to ripen on the vine, but was still tough enough to resist rotting. This meant it could survive both mechanical harvesting and the thousand-mile truck to market.

In 1994, after three years of negotiations with regulators, the Flavr Savr became the first genetically modified food approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to be sold in American supermarkets. Rather than being declared formally “safe,” the Flavr Savr was considered the “substantial equivalent” of a normal tomato. At the time, few people complained, and suspicious critics of genetic engineering were largely drowned out by cheerleaders in industry and the press.

To be honest, as a budding English professor, I could never muster much enthusiasm for a product spelled Flavr Savr. The phonetically engineered name offended my ear even before I considered the tomato’s provenance or taste, or the many ethical questions surrounding its creation. I decided to save my money, and keep grading papers.

But the Flavr Savr, it turned out, was just the beginning of what would become a food revolution. Soon I started hearing stories about another tomato, this one by a company called DNA Plant Technology, which was being outfitted with genes from an Arctic flounder. These “fish tomatoes,” the company hoped, would make plants resistant to frost and cold storage, making them easier to grow in northern climates.

In 2001, researchers unveiled a third tomato, this one capable of growing in salty soils—a good thing, since modern irrigation practices were damaging soil so much that the world was losing 25 million acres of cropland a year. The fish tomatoes never made it to market. So far, neither have the salt-tolerant tomatoes. The Flavr Savr tomatoes made it to market briefly, but they were a commercial flop. The ingenuity of a human-engineered tomato never quite overcame the consensus that the Flavr Savrs tasted terrible.

Now, more than twenty years later, these moribund tomato experiments seem almost quaint. Today, nearly all of our calories— that is to say, nearly all of our food—are grown from genetically modified plants. Chances are that three-quarters of everything you’ve put in your mouth today—the eggs, the yogurt, and the cereal; the chicken sandwich, the tortilla chips, the mayonnaise, and the salad dressing; the cheeseburger, the French fries, the soda, the cookies, and the ice cream—were processed (or fed) from plants grown from seeds engineered in a laboratory. Same for the food you feed your baby and the food you feed your dog.

The reason for this is simple: The American diet is composed almost entirely of processed foods that are made from two plants—corn and soybeans (and canola, if you want your food fried). Their seeds, full of dense calories, can be broken down and reconstituted into an infinite variety of prepackaged foods. The vast majority of the 40,000 food products Americans choose from every day are built from ingredients made from engineered plants. Fully 85 percent of the feed given to cattle, hogs, and chickens is grown from genetically modified crops. There’s more: About half of the sugar we consume is grown from engineered sugar beets.

Strangely—and despite the fact that we’re talking about plants—the one place you mostly won’t find engineered food is in the produce aisle. Your carrots, your peaches, your lettuce—they are all grown the old-fashioned way. (This, by the way, is true whether or not the produce is labeled “organic.”) But travel to the middle of your supermarket—or into most fast-food restaurants, convenience stores, or gas stations—and you will discover GMO foods at every turn.