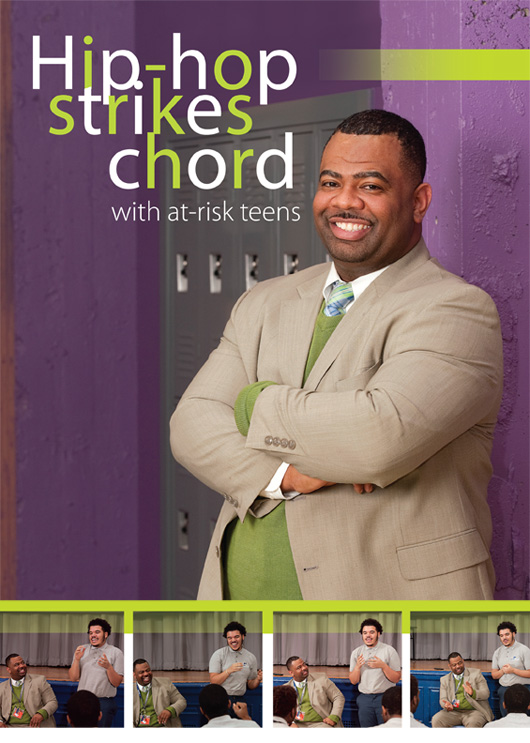

ALUMNI | Growing up in a troubled neighborhood in Columbus, Ohio, Anderson says he was blessed with an exceptional mentor, who ran a program called the Self Esteem Team. Alfred Ray used critical-thinking games, music and other unconventional techniques to motivate and challenge disadvantaged youths. His Self Esteem Team not only helped Anderson stay on track, he says, but also inspired him to combine music and education to help other youngsters.

After receiving an undergraduate degree in music from Xavier University, Anderson headed to Florida State University to obtain a master's degree in education. While student teaching there, he was asked to help a class of behaviorally challenged youngsters and decided to incorporate hip-hop music into the curriculum to motivate and educate them. The program had such successful results, it caught the eye of Shuaib Meacham, an associate professor of education at UD.

Meacham had been working with a teacher at Talley Middle School, using hip-hop to inspire students to improve their language skills. In 2002, he invited Anderson to enroll in the UD doctoral education program and help develop an after-school program, similar to his curriculum in Florida.

As part of the program, students were requested to develop a business model they could implement. One ambitious eighth-grader, aspiring to be a music producer, asked to create a music studio.

The idea was intriguing. Anderson, Meacham and Jennifer Bishop, who also was working with the program at Talley, applied for a grant, and slowly the dream of a music studio was realized.

"Tony brought a unique combination of skills to the program," Meacham says. "Not only had he worked in youth programs and had formal teaching credentials, he had experience recording and producing music. As a producer, he knew how to work with and motivate different personalities, how to help them set goals and achieve them."

Working with Anderson, the students began to compose and perform hip-hop music that addressed the complex issues and challenges they were facing. Once they had enough songs, they produced a CD and began selling it under the moniker Bassline Entertainment.

Suddenly, these previously disenfranchised middle school students became engaged and motivated, Meacham says. They were going to class and paying attention.

"These were adolescents who were barely staying in school," he says. "Most had serious behavioral issues and little to no interest in academics. But once they had the opportunity to work in the studio, they didn't want to leave school."

The program provided such a positive influence that the students didn't want the experience to end. As a show of support for their efforts, Anderson decided to develop a summer program.

He approached the University and asked if he could hold a summer camp for participants to learn about the music business. "I was very fortunate that UD liked the idea," Anderson says. "They were willing to support me. It allowed the kids to take their experience to the next level."

The four-week program not only helped the students learn to be better performers, it also introduced them to all aspects of the music business. Anderson brought in industry professionals, lawyers, designers, writers and engineers, to demonstrate the wide breadth of opportunities available for people interested in music.

With all this musical knowledge, the students began wanting to perform for real, and they started traveling to small venues along the East Coast. As a special treat, Anderson arranged a trip for them to perform at the Indianapolis Black Expo, where he says they gained valuable insight into the challenges of professional entertainment.

Shortly after that performance, they learned that Sheffield College in England was looking to incorporate hip-hop into its curriculum and that educators there were impressed by the success of Bassline. Anderson says the group was stunned when the college invited Bassline over to perform, but happily complied.

The hip-hop curriculum may have opened a whole new world for these students, but Anderson's impact was not limited to the music. Despite their backgrounds, he says, every student in Bassline graduated from high school and was admitted to a four-year college—with many receiving music and performance-based scholarships.

One of those students, Shanice Griffith, now attends UD. A senior majoring in sociology with a social welfare concentration and minors in psychology and Spanish, she explains how Anderson kept his students motivated in middle school:

"Dr. Anderson continuously asked us what we desired for our futures. He helped us set goals and develop plans that would lead us to them. After spending an incredible amount of time with him and learning from his thoughts, ideas and teachings, I feel as though I have inherited his motivational spirit. I work at UD as a mentor, Blue Hen Ambassador and resident assistant, providing assistance and guidance to others in the same way Dr. Anderson provided it to me."

His former students say the most important message Anderson taught was that they could rise to any challenge and succeed, that all they needed was to believe in themselves. Many have become entrepreneurs, creating their own path forward.

"Tony changed my whole perspective in life," says Mike Jaggerr, a Bassline student who now has a career writing and producing his own music and videos. "Growing up without a father in the home, it felt like I was continually searching for something or someone to lead me. Then, in eighth grade, I met Tony. He understood me, my particular background and how that affected my scholastic endeavors. He taught me how to lead. Once I realized that I had that power, I haven't looked back."

A continuing impact in education

While pursuing his doctorate in education, Anderson taught classes at UD and, in 2008, was awarded the Excellence in Teaching Award for a graduate student.

"Tony enjoys teaching," says Bob Hampel, director of the School of Education "You can tell it by the interactive and engaging methods he uses to reach his students. When teaching 'Urban Schools and Urban Landscapes' this past fall, he incorporated movies, video clips and real-world experiences. He helped students understand the complex issues faced by today's educators, and as a result their instructional repertoire as new teachers will be broader."

Anderson says he continues to teach at UD to help guide future classroom teachers and future generations of students: "I'm not only having an impact on [UD education students]. They will go out and become teachers, with each of them reaching maybe 100 students every year. What they learn from me can influence thousands of children. It is a significant responsibility, but I love the challenge."

After receiving his doctorate, Anderson joined the Mastery Charter School in Philadelphia as an administrator of the network of schools brought in to help turn around failing public schools. Mastery Charter raises the bar for urban education, Anderson says, by living the motto, "Excellence. No Excuses."

Anderson "plays a critical role in our program," says Matthew Troha, principal of Mastery Charter School's Thomas Campus. "As a dean of school culture, he is charged with ensuring that our students feel safe, supported and positive about themselves and their education. Dr. Anderson's ability to hold all students to high standards while also building their trust is rare. I'm fortunate to have such an intelligent, caring and determined educator on my team."

Continually looking for new challenges, Anderson describes his ultimate goal. "I'd love to be chancellor of a school," he says. "I want to be the one making the decisions, setting the path and implementing the programs I think will work. Being an administrator at Mastery has shown me this would be a very complicated and involved project, but the rewards are great. I want to see kids succeed."

Article by Alison Burris, BE85