Category: Art Conservation

Art conservation and fragile histories

December 30, 2025 Written by Lisa Chambers | Photos by: Evan Krape and Elizabeth Glander

For Elizabeth Glander, a second-year paintings major at the Winterthur/University of Delaware Program in Art Conservation, connecting with the people who love and live with art is part of what makes her work so meaningful.

Art conservation often begins not with a brush or a microscope, but with a conversation. For Elizabeth Glander, a second-year paintings major at the Winterthur/University of Delaware Program in Art Conservation (WUDPAC), connecting with the people who love and live with art is part of what makes her work so meaningful.

“One of the things I love about conservation, besides getting up close and personal with the art—being hands-on to help it live a long life,” Elizabeth said, “is interacting with the owners of the artwork.” She recalled a conservation clinic where an elderly woman brought in a family book. “She was talking about her relatives from Scotland who started this book generations ago. She was terrified of hurting it,” Elizabeth said. “It’s hearing those stories that makes it more than just a book or a painting and helps bring it to life.”

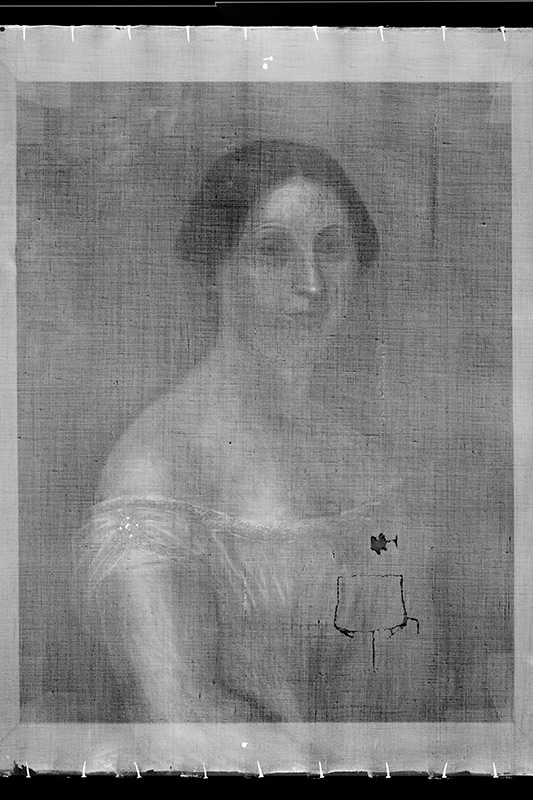

That spirit of connection guides Elizabeth’s current treatment of a mysterious Portrait of a Woman. A recent Winterthur acquisition, the lady hasn’t relinquished her secrets easily. She was painted by Swiss-born Hans Heinrich “Henry” Bebie, a 19th-century artist who emigrated to the United States, settling in Baltimore sometime in the 1870s. “He was best-known for his upscale brothel interiors and portraits of Baltimore’s wealthy families,” Elizabeth discovered. But with little other information available, she added, “We don’t know if she was a real person.”

The painting showed signs of aging—grime, two layers of varnish, and a couple of damaged spots: a small L-shaped tear near the shoulder, and a more complex tear at the woman’s chest, previously patched. Elizabeth plans to reverse that earlier treatment and instead use a more refined approach: thread-by-thread tear mending, a technique she learned during an internship at the National Gallery of Art.

Looking through a microscope at each individual fiber, Elizabeth will use “tiny little tools,” including dental picks, insect pins—and even cat whiskers—to apply the adhesive, made of a blend of sturgeon glue and wheat starch paste. “Sturgeon glue is a very strong glue, and the wheat starch paste is added to provide it some flexibility after it dries,” she explained. “You take a drop of adhesive on one tool, and then less than a drop on another, and apply it onto the individual thread fibers, gluing them back together. When it’s done correctly, it can be pretty invisible.” Though the portrait’s history may remain uncertain, Elizabeth’s care ensures the painting will endure—and perhaps inspire new stories along the way.