Q and A

A conversation with Jelani Cobb

11:48 a.m., March 3, 2015--A daylong symposium “The Difficult Conversation: Race and Social Justice in America,” held Feb. 26 at the University of Delaware, was an effort aimed to encourage open dialogue in our academic community about social issues that currently affect our world.

Interactive modules during the day were followed by an evening lecture with scholar and author Jelani Cobb, who is associate professor of history and director of the Africana Studies Institute at the University of Connecticut.

People Stories

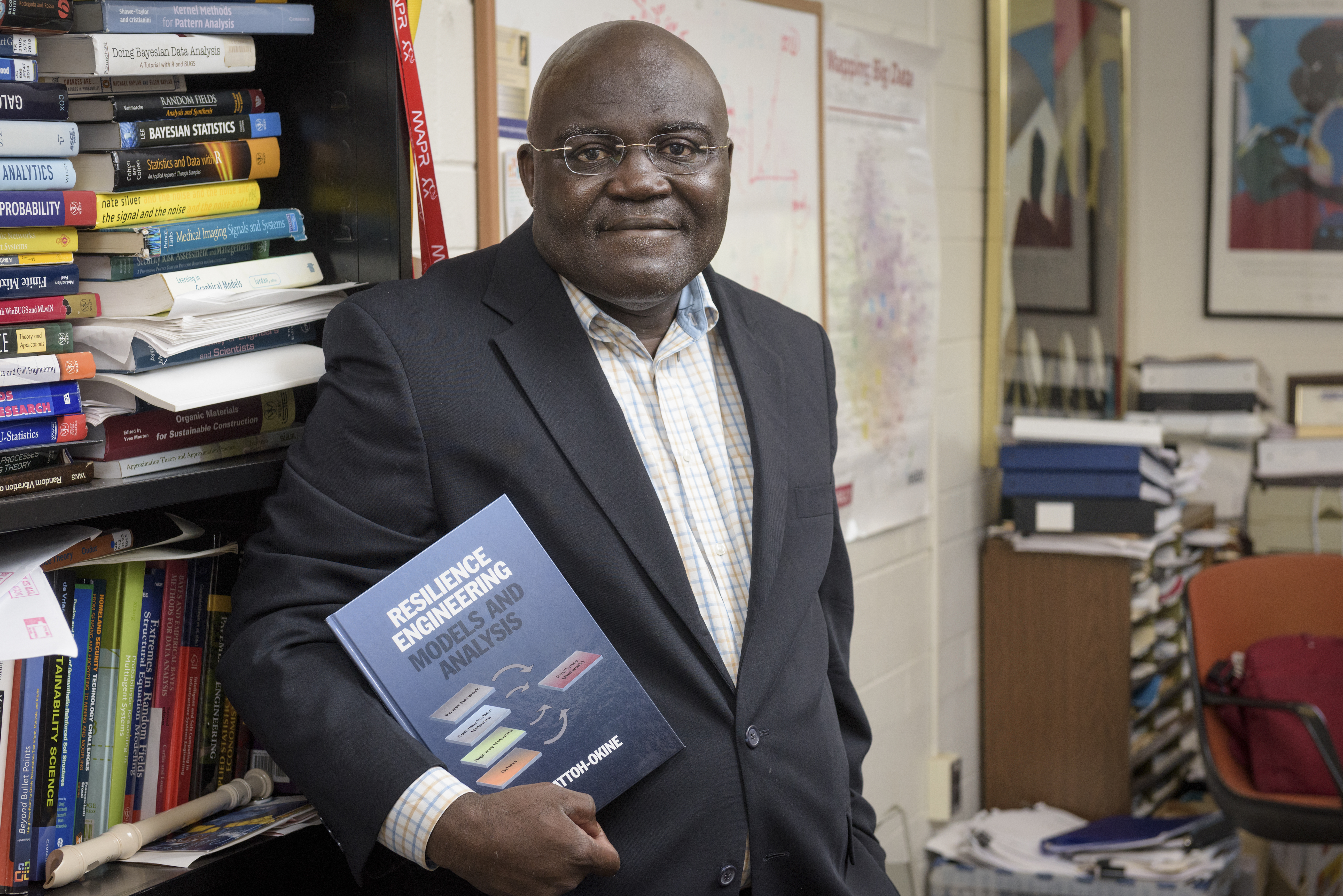

'Resilience Engineering'

Reviresco June run

In a Black History Month lecture, he spoke on “Struggles for Black Freedom in the 21st Century.”

Cobb graciously sat down with UDaily to discuss key elements of his speech.

7 Questions for Jelani Cobb

Q: Good morning. Thanks for your time.

JC: My pleasure.

Q: Your original dream jobs were firefighter, speechwriter and train conductor. How did you decide?

JC: (Laughs) Actually, those are mostly just childhood ambitions. Speechwriter was an idea from college, but I didn’t pursue it.

As for as the other two dream jobs, in childhood I said, ‘I want to be a firefighter, I want to be a train conductor.’ In the back of my mind I still think, ‘Those would be cool things to do.’

Q: Same question. How did you decide on historian?

JC: When I went to Howard University my freshman year, I was an English major. I took a black diaspora class, but I had absolutely no reference for any of the things the professor was talking about.

That experience just opened up an entire area of inquiry for me. So I became fixated on history and how history could illuminate the present.

Q: There’s that hackneyed adage that if we don’t study history we are destined to repeat it. As a distinguished historian, can you offer something more marketable?

JC: (Laughs) Sometimes we study history and we still repeat it. But even if we do, the hope is that we are gradually coming to a place where we understand things more clearly.

I always tell my students: ‘History doesn’t repeat itself; humans do.’ So it’s not that history is some abstract force in the universe like gravity, over which we have no control.

Q: During your Black History Month lecture, you drew a thematic line from Michael Stewart (who was choked by NYPD in 1983), Radio Raheem (a character from Spike Lee’s “Do the Right Thing,” based on Stewart) and Eric Garner (whose 2014 death was triggered by a chokehold by NYPD). What does that signify about policing, particularly in communities of color?

JC: It says that these have been problems for a long time.

Some of the issues aren’t even specific to policing. I was talking to someone last night, for example, and said it’s not like we will have a fair and just criminal justice system and still have a bad educational system. Or have a great educational system and still have a terrible housing system. So there’s a more fundamental question about how we deal with poor people and people of color.

And those problems have been in existence since the beginnings of this country. There is a reason those issues arise again and again: It’s because we have not resolved the underlying conflict.

Q: Taking that idea further, you visited Ferguson, Missouri, (site of teenager Michael Brown’s death at the hands of police) four times. One of the most telling images you shared was a solider sitting on an armored vehicle aiming an assault rifle at unarmed people.

JC: A good number of people saw that as saying that we are now at a point in which our police are functioning like military — and this is something we should be very concerned about. When you see imagery and it is identical almost to what you see of people being deployed to Iraq or Afghanistan, that tells you something about the nature of what policing does in our country.

When we talk about policing, we often talk about it in the context of stopping crime — which is important. That’s one of the things policing does. But it also has historically been, especially for people of color, a means of social control.

You don’t typically need an armored vehicle to solve a crime.

Q: Speaking of social control, a theme you threaded throughout your lecture was how this nation was developed — from its inception till today — asserting control over the bodies of people of color. How do we juxtapose that against our alleged ‘post-racial society’?

JC: The nature of Obama’s presidency was almost inevitably going to highlight the fact that this is not a post-racial society. Consider the things with which he would be confronted — being called a liar during his State of the Union address, the racialized rhetoric questioning his citizenship, the notion of his being a clandestine Muslim communist and these bizarre conspiratorial ideas.

All these things highlight the reality that we are not in a post-racial society.

The night Barak Obama was elected, black unemployment was still significantly higher that white unemployment. So a single electoral reality was not going to change the socioeconomic reality of millions of people.

Q: Delaware students have used thoughtful acts of civil disobedience to address issues around identity, sexual assault, race and religion. The University is also currently engaged in a social media campaign #VoiceofUDel to promote respectful candor. You mentioned a concept of “contingency citizenship” that parallels notions of inclusion and acceptance within a community. If you could add your voice to the campaign, what would you say?

JC: Contingency citizenship means you have rights in a certain context, with certain contingencies. But when you step outside those contingencies, your rights can be revoked. An example is Eric Garner, who was put in an unsanctioned chokehold and died, yet there was no grand jury indictment, which says there was no wrongdoing.

So it’s the most fragile freedom.

Event sponsors

Cobb's lecture was hosted by the Department of Black American Studies and sponsored by the College of Arts and Sciences, the vice provost for diversity, University Museums, the Center for Black Culture, the Center for the Study of Diversity, the Department of History, the Department of Political Science and International Relations, the School of Public Policy and Administration and Nu Xi Chapter of Kappa Alpha Psi Fraternity.

Article by Jawanza Ali Keita

Photo by Duane Perry