Beach safety study

UD researchers and partners assess wave processes, injury occurrence along Delaware coast

4:34 p.m., June 16, 2014--Have you ever turned your back to the ocean “just for a second” while standing at the water’s edge, only to be thrust into the sand by an oncoming wave?

The force of those breaking waves can be intense, and an ongoing study finds that beach injuries are surprisingly common. Hundreds of swimmers and waders in Delaware alone visit the emergency room each year with injuries ranging from minor cuts to broken bones, blunt organ trauma and spinal fractures. Nationwide, the numbers could be much higher.

Research Stories

Chronic wounds

Prof. Heck's legacy

Medical experts and University of Delaware researchers are examining wave processes along the coast in an effort to relate beach conditions to injury occurrence. In a detailed study, they are cross-referencing wave properties —such as height, wave length and where the waves break — with injury statistics. This summer they are installing special gauges at beaches that measure wave properties and currents to improve data collection for the study.

“If the beach drops off steeply, it affects how the waves change as they come in to the shore,” said Jack Puleo, associate professor in civil and environmental engineering at the University of Delaware’s Center for Applied Coastal Research and principal investigator on the pilot study funded in part by the Delaware Sea Grant College Program.

On the northern part of the West Coast of the United States, Puleo explained, many beaches tend to have shallow slopes and waves form and break multiple times before they reach the shoreline, which diminishes their power. Along some portions of the East Coast, the beaches are steeper and allow waves to break closer to the shore. Under the right conditions, the breaking location might be in just a few feet of water, right where people are wading.

“This causes all of the wave’s energy to be released in a very narrow location, which we hypothesize may contribute to injuries,” said Puleo, who holds a joint appointment in UD’s College of Earth, Ocean, and Environment in physical ocean science and engineering. “The distance between waves and the slope of the beach can affect how or where a wave breaks relative to the shoreline, and we want to know if these wave breaking variations are related to injuries.”

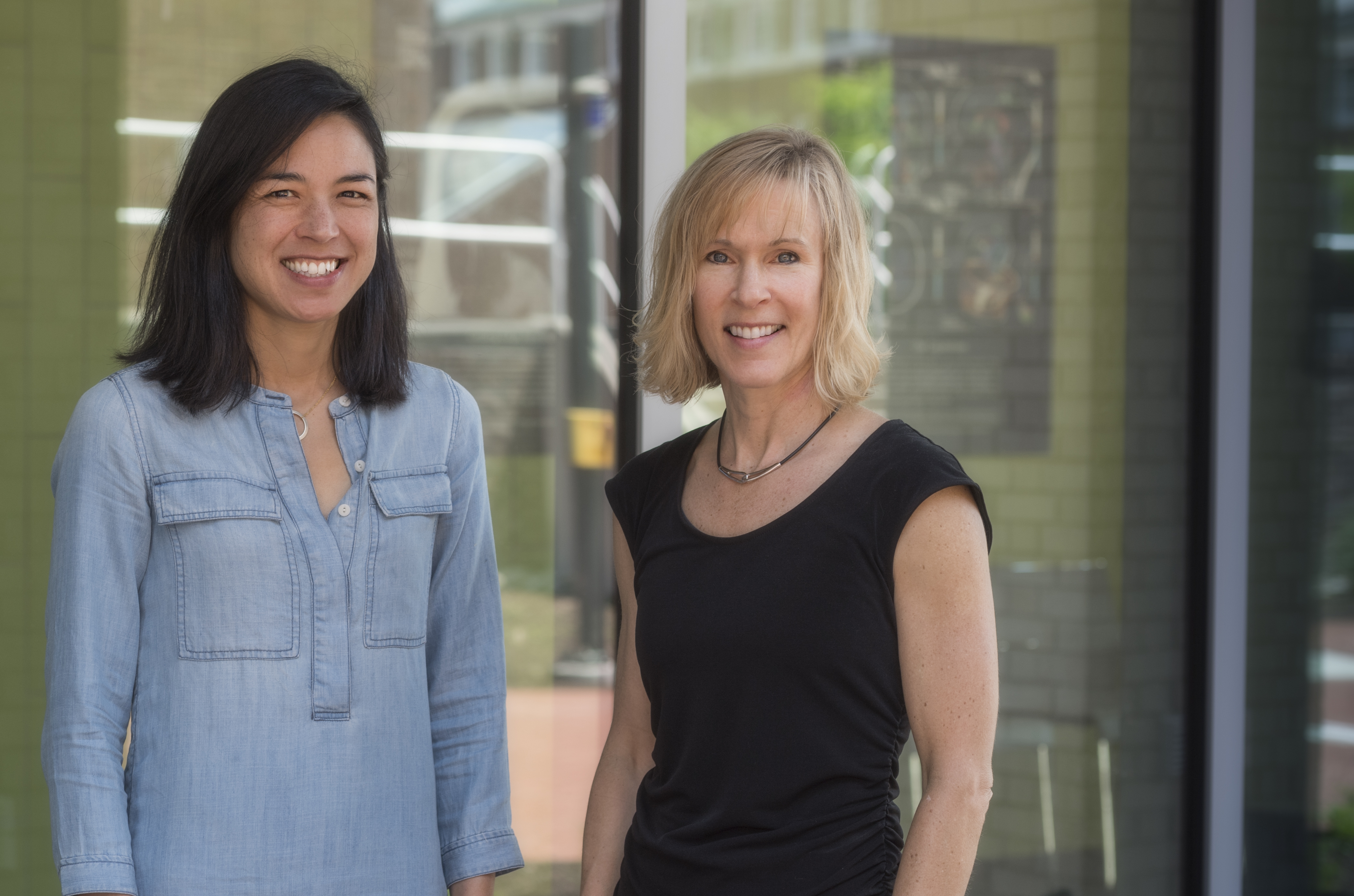

Researchers began exploring the connection between beach conditions and injuries several years ago. Paul Cowan, Beebe Healthcare chief of emergency medicine, suspected that clusters of emergency room visits were associated with rough surf conditions and contacted Delaware Sea Grant’s Wendy Carey to integrate beach dynamics, weather conditions and observations from local beach patrols into a formal study.

From 2010-13, they documented 1,239 emergency department visits by Delaware beachgoers to treat broken collarbones, sprained ankles, neck pain and various other ailments.

The team also collected daily information on wave height, weather conditions, the number of people in the water, patient demographics and additional metrics to look for trends.

Preliminary results suggest that most injuries occur when waves are greater than 1.5 feet, and swimmers over the age of 45 who frequently visit the beach may be at greatest risk.

Carey, a coastal hazards and resiliency specialist with Delaware Sea Grant, specializes in how beach dynamics affect coastal communities, from erosion to storm impacts and preparedness. She has been instrumental in public awareness campaigns about rip currents, which can make it difficult for swimmers to get back to shore.

The surf zone injury study could result in a similar education effort for visitors to Delaware beaches, and potentially expand to other states where similar situations are suspected. Safety tips include understanding the power of the ocean, not turning one’s back to the waves, and asking lifeguards about conditions for the day.

“Ultimately, a project goal is to improve public safety by identifying key target audiences for awareness messages,” Carey said.

This summer, the researchers will take an even closer look at which environmental conditions may be related to the injuries. They have installed wave gauges about 100 yards offshore at five Delaware beaches: Cape Henlopen State Park, Rehoboth Beach, Dewey Beach, Bethany Beach and Delaware Seashore State Park.

The sensors, called acoustic Doppler current profilers, use sound frequency to measure wave period, direction and height.

“These data are critical to the study because the sensors will be located as close as possible to the area where breaking waves may impact water users,” Puleo said.

Beginning June 1, two UD engineering students also began taking daily measurements of the profile and slope of the beach using a global positioning system (GPS) and count how many people are in the water at a consistently designated time of day. Comparative data will be collected monthly to account for daily variability at each beach.

In particular, the researchers will be looking for any relationship between the number of water users, foreshore steepness and wave characteristics.

They hope the study will enable them to relate parameters that describe some characteristics of how waves break to injury occurrence. This information could be helpful, Puleo said, for things like lifeguard staffing.

“Lifeguards cannot stop someone getting knocked over by a wave. They can’t always keep people out of the water, but maybe down the road people will be able to download an app to determine whether ocean conditions are especially hazardous on a given day,” said Puleo.

Collaborators on the Delaware Surf Zone Injury Study include Beebe Healthcare, Delaware Sea Grant, University of Delaware College of Earth, Ocean, and Environment, School of Marine Science and Policy, UD’s Center for Applied Coastal Research, Delaware Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Control (DNREC) Shoreline and Waterway Management Section and Atlantic Ocean beach patrols from Rehoboth Beach, Dewey Beach, Bethany Beach and DNREC State Parks.

Article by Karen B. Roberts and Teresa Messmore

Photos by Lisa Tossey and Evan Krape