The people pipeline

Student's story illustrates how Delaware EPSCoR supports developing scientists

2:22 p.m., Sept. 12, 2012--Just as laboratories need pipelines for water and natural gas, they also need a “pipeline” that provides a continuous supply of people able to conduct research there.

Making sure the people pipeline is full of well-trained individuals from its source in the elementary grades to its outlet in the academic and commercial laboratories of the world is one of the most important goals of Delaware’s Experimental Program to Stimulate Competitive Research, or EPSCoR.

People Stories

'Resilience Engineering'

Reviresco June run

“Expanding the pipeline of students pursuing science, technology, engineering and mathematics — or STEM fields — is a matter of national importance,” says Jeanette Miller, director of education, outreach and diversity for Delaware EPSCoR. “The cornerstone of EPSCoR is building research capacity through infrastructure improvements, and that includes developing people as well as building facilities and buying equipment.”

By linking the four institutions of higher education in Delaware that offer science degrees, EPSCoR also provides alternative pathways for nontraditional students and members of underrepresented groups that might not otherwise find their way to a STEM career. Pursuing a research career can be daunting, but Delaware EPSCoR provides both the financial and personal support that aspiring scientists often need to persevere.

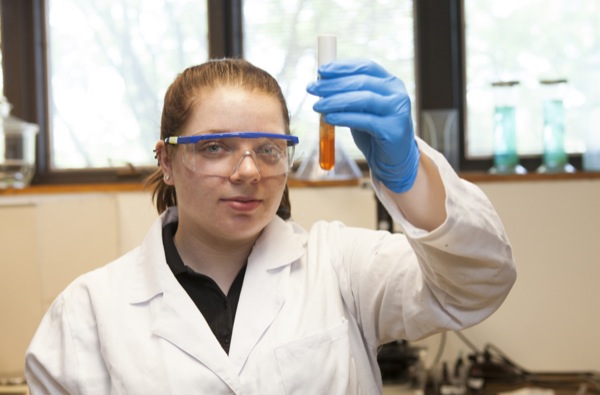

For Mollee Crampton, a second-year master’s student in biological sciences at UD, that support has been a key component to achieving her goals. Crampton’s journey illustrates how the statewide EPSCoR network links what might otherwise be disjointed steppingstones into a smoothly flowing pipeline of higher education.

A resident of Kent County, Del., Crampton attended Caesar Rodney High School. There she dreamed of pursuing a degree at the University of Delaware, but finances were an obstacle. In Crampton’s case, a combination of state and national funds, including support from the EPSCoR program, has been instrumental in shaping her journey.

Rather than applying to UD initially, Crampton took advantage of a new state scholarship program and a program for STEM students sponsored by the National Science Foundation (NSF). The SEED (Student Excellence Equals Degree) Scholarship program, funded by the state of Delaware, enables students to pursue an associate degree from Delaware Technical Community College for free if they meet certain basic qualifications. The NSF Scholarship in Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics (S-STEM) is meant to stimulate undergraduates to pursue degrees in these four critical areas.

When Crampton completed her associate degree in biotechnology in May 2009, her adviser at Delaware Tech, Barbara Wiggins, encouraged her to apply to a Research Experiences for Undergraduates (REU) internship program in molecular genetics and genomics at Delaware State University for the following summer. One of several REUs in Delaware supported by NSF, the program places undergraduates in research laboratories for the summer, allowing them to make real contributions to the investigations under way. Crampton’s internship was hosted by Venu Kalavacharla, associate professor of plant molecular genetics and genomics for the College of Agriculture and Related Sciences and director of the REU program at Delaware State.

Kalavacharla’s lab also receives EPSCoR research funding, which made all the difference to Crampton. After her summer REU, she was hired to continue working in the lab during the academic year.

“They paid me to do research,” she says,” so I spent a lot more time in the lab than if I had also needed to work in a restaurant or something.”

As a student researcher, Crampton worked with the common bean, which includes “most species of bean that are normally eaten, except for soybeans,” she says. Much of her effort focused on discovering genes for disease resistance. She compared genetic variations in the bean genome to the genome of Arabidopsis, a plant commonly used as a model by plant geneticists because its genome has been completely sequenced. Crampton also played an active role in mentoring other undergraduate students and exciting them about the possibilities of research in biology. The positive experience encouraged Crampton to finish her degree at Delaware State.

In 2010, she attended a regional agricultural conference in Atlanta held by the 1890 Association of Research Directors (ARD). “Being able to present a poster about my research at a regional event was excellent preparation for graduate school,” she says.

She also worked with other researchers in the Kalavacharla laboratory and co-authored a peer-reviewed manuscript that was published in March 2012 in BMC Plant Biology.

Crampton received a bachelor of science degree in biology with a concentration in biotechnology in May 2011 with a 3.95 grade point average. That summer she was awarded the University of Delaware’s Bridge to the Doctorate (BD) graduate fellowship to pursue an advanced degree in biology. The BD fellowship is funded by NSF to promote the participation of underrepresented students (including women) in STEM disciplines.

Her current research focuses on antimicrobial resistance using Salmonella bacteria. She works under the supervision of Diane Herson, associate professor in the Department of Biological Sciences at UD.

Crampton is also involved in a collaborative project with Pennsylvania State University, where researchers are seeking ways to deal with a glut of used tires by grinding them up into crumb rubber and applying them as a soil amendment. However, tires are known to leach chemicals when exposed to an acidic environment, such as acid rain. Crampton is studying Salmonella as a model organism to discover the effects of the leached chemicals on bacterial growth.

“We want to know whether the leachate is an inhibitor of bacterial growth or whether it allows bacteria to propagate more freely. Either property could have serious consequences on the local environment,” says Crampton.

Crampton is currently pursuing the molecular biology and genetics track at UD and hopes to work in research and development for a pharmaceutical or biofuel company after obtaining her Ph.D.

“One thing led to another from Del Tech to my internship, and then from Del State to the University of Delaware,” she says. “I’m really grateful that EPSCoR has been there to help support me in reaching my goals, and I’d like to give back by encouraging other students to do the same and by contributing productively to our society.”

According to Kalavacharla, Crampton’s adviser at Delaware State and member of the Delaware EPSCoR leadership team, Crampton and other students like her might not have access to the pipeline of Delaware institutions without the relationships forged by EPSCoR.

“Thanks to EPSCoR, we all have much better knowledge about what opportunities exist at each of our institutions and can direct students accordingly,” he says. “The pipeline is alive and well in Delaware.”

Article by Beth Chajes and Jacob Crum

Photo by Ambre Alexander