'Immortal Life'

Author Skloot recounts scientific legacy of Henrietta Lacks

2:01 p.m., Oct. 14, 2011--Even as a youngster, Rebecca Skloot wasn’t afraid to question authority and raise issues that others discounted or discarded.

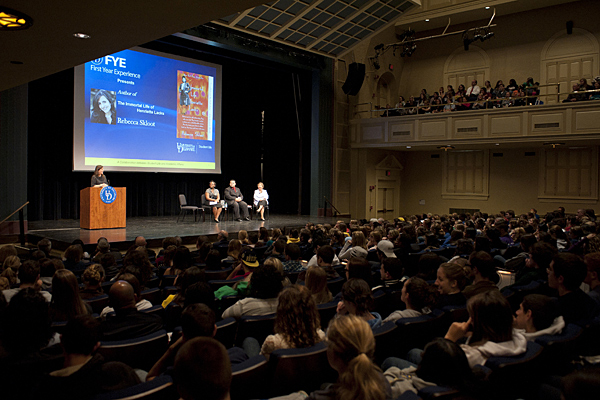

The author of the acclaimed book The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks shared her journey from a one-time rebellious student to an award-winning journalist with University of Delaware freshmen during a First Year Common Reader program talk on Thursday, Oct. 13, in Mitchell Hall.

People Stories

'Resilience Engineering'

Reviresco June run

More than 650 students attended the event, joined by an additional 200 students who watched remotely via simulcast in the Trabant University Center Theatre.

University President Patrick Harker welcomed an audience that also included Henrietta Lacks’ son, David (Sonny) Lacks, and his daughters, Kim Lacks and Jeri Lacks-Whye and son-in-law Thomas Whye.

“Since The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks was published last year, Mr. Lacks has visited universities and libraries across the country,” Harker said. “David has been talking about his mother’s legacy and how her biological immortality has affected his family, and also about bioethics and exploitation, race, class and the ownership and commodification of our DNA.”

Translated into 25 languages, Skloot’s book brings to light the story of a poor African-American migrant from the tobacco farms of Virginia who died from cancer at age 30 in 1951.

A sample of Lacks’ cancerous tissue -- known as HeLa cells after the first two letters of her first and last names -- became a building block for major medical breakthroughs, including the polio vaccine, chemotherapy, cloning, gene mapping and in vitro fertilization.

In noting that UD freshmen missed the first week of the academic year because of Hurricane Irene, Skloot told the audience that her talk would be part Convocation and part discussion about the book.

“About a year ago, I was on a TV show talking about the book, and the woman who was talking to me said at some point, ‘Were you one of those students who got straight A’s and had everything all figured out that you wanted to be a writer?’” Skloot said. “I had to laugh to myself because there is nothing further from the truth.”

Skloot described herself as a student who possessed a strong sense of independence with little interest in subjects that bored her.

“I was hard-headed, and when I wanted to do something, nothing could stop me from doing it,” Skloot said. “I was a smart kid who had a lot of energy and hadn’t figured out how to channel all that energy in a positive direction.”

Skloot urged students to look out for those “what” moments when a person hears something that piques their curiosity and makes them want learn more about the subject.

Such a moment occurred when Skloot heard about Henrietta Lacks and her family, and why they were not told about the HeLa cells until 25 years after those cells were taken in a laboratory at Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore.

“There was something about that woman that I wanted to know about,” Skloot said. “When I was in grad school, I was asked to write a series of essays on forgotten women in science. The first name that came to mind was Henrietta Lacks. That was the day I started to track down the Lacks family.”

Skloot said that the desire of Henrietta Lacks’ daughter, the late Deborah Lacks Pullum, to see that her mother’s story was made known to the public helped sustain the author during the decade-long writing process.

“She wanted to share her mother’s contribution to science,” Skloot said. “She also wanted to see more sharing of the scientific knowledge, which she felt was withheld from her family for so long.”

While the relationship with Deborah Lacks was at times tumultuous, a gradual sense of mutual trust developed between the two women, who both wanted the world to learn about Henrietta Lacks and her remarkable contribution to science.

“It took about a year and a half to win her trust,” Skloot said. “She would become upset with me, and in those moments she would immediately recognize what was happening. It wasn’t that she didn’t trust me; she didn’t trust anybody after what had happened to her mother.”

After her talk, Skloot fielded student questions presented by a panel moderated by Margaret Andersen, associate provost and Edward F. and Elizabeth Goodman Rosenberg Professor of Sociology. The panel also included sophomore Quindara Lazenbury, psychology education major with a Spanish minor, and senior Gabriel Mendez, a double major in political science and communication, both peer mentors through the University's First Year Experience program.

Article by Jerry Rhodes

Photos by Kathy F. Atkinson