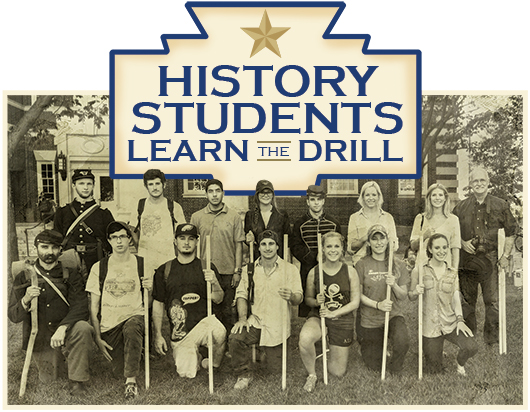

ON THE GREEN | Never mind that they were dressed in jeans and T-shirts, some in tank tops and running shorts. Never mind that they carried long wooden dowels instead of muskets, marching in formation on The Green and not a Civil War battlefield.

On a warm afternoon during fall semester, Ritchie Garrison’s History 411 students were learning drills and marches like Union soldiers.

“I am going to let our officers issue non-lethal muskets, which I bought at Home Depot this morning,” said the smiling professor of history and director of the Winterthur Program in American Material Culture. He handed long wooden sticks to his two doctoral students, Lucas Clawson and Tyler Putnam.

Unlike the undergraduates, Clawson and Putnam were dressed the part. Clawson was a soldier, complete with full beard, forage cap and blue wool coat. Putnam, a second lieutenant, wore a Prussian-blue officer’s coat and kepi hat. Both UD graduate students also happen to be Civil War re-enactors.

The day was one of the highlights of Garrison’s course, “The Emancipation Project,” in which undergraduates are creating a digital version of a Civil War diary passed down to Garrison by his great-uncle, John Ritchie, a quartermaster of the Massachusetts 54th Black Regiment. Working with the History Media Center’s media specialist, Tracy Jentzsch, the students are helping make this diary accessible to everyone.

“They are proofreading the diary and writing a series of short papers, to be published alongside the diary to make it publicly available to anyone who would like to read it,” Garrison said. “They are crowdsourcing the information.”

Jentzsch filmed the students as they learned commands such as “right face” and “parade dress.” She and Garrison were impressed by how quickly the students learned the techniques. The video she took will become part of the digital project.

“Even though it’s an analog kind of day, they will turn this into a digital aspect when the students begin editing the video,” Jentzsch said.

For undergraduates, the course offers a rare opportunity to work with original historical documents, to publish their own research online for distribution and to actually become a part of what they are learning, Garrison said.

On this humid day, sunlight dappling through the trees, the juniors and seniors listened intently as Clawson and Putnam taught them how to stand at “dress,” or lined up closely shoulder to shoulder. They learned how to march with and without “doubling” (side by side and in single file) and how to “fall in” as they made their way across the lawn.

Like a unit in training, the students marched, taking their roles seriously.

“It’s very complicated,” said senior Connor Gerstley, a double major in history and English. “There is much more to this than I ever imagined.”

Garrison’s class had studied the Army Manual of Arms, but actually following it really brought the lesson home for the class.

“You can read about it all you want,” he said to his students. “But you’ll always remember this day. You’ll be telling your grandbabies about it.”

The experience that day, and throughout the course, was for another purpose, too. It was to teach the students about the role of African Americans soldiers in the Civil War and to examine how their service moved the needle ever so slightly on the racial prejudices of the time.

The diary from the Massachusetts 54th was one of two passed down to Garrison. The other came from his great-grandfather, George T. Garrison, who was an officer of the Massachusetts 55th Black Regiment. Both were some of the first units made up exclusively of African American soldiers, led by white officers.

“The course project is to get students thinking about the way military experience shaped the lives of men who were African American,” said Garrison, noting that most of the enlisted volunteers were freed slaves.

The soldiers, regardless of their skin color, were treated according to the same military standards. They drilled and trained just like their white counterparts and, for the most part, were treated with a good deal of respect from their officers. By the end of the war, black men had begun to achieve the rank of sergeant and three out of the 100,000 African American men who served had earned first lieutenant status.

“It really did change people’s opinions when black troops fought as well as white,” Garrison said.

Article by Kelly April Tyrrell